| NCERT Exemplar Solutions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

| Content On This Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Section A | Section B | Section C |

| Section D | ||

Class 9th Mathematics Sample Paper Set I (NCERT Exemplar)

Welcome to this crucial section featuring meticulously designed Sample Papers accompanied by their comprehensive solutions, specifically tailored for Class 9 students preparing for examinations that emphasize conceptual depth and application skills. These sample papers are far more than simple practice sets; they are constructed with the express purpose of providing a truly realistic assessment experience. Every effort has been made to mirror the anticipated difficulty level, the diverse typology of questions (ranging from objective to subjective), and the proportional chapter weightage that students are likely to encounter in final assessments, particularly those incorporating Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) and application-based problems characteristic of the demanding NCERT Exemplar series.

Accompanying each sample paper is a dedicated solutions page, offering complete, step-by-step answers and thorough explanations for every single question presented. This holistic support covers all formats you might face:

- Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs)

- Fill-in-the-Blanks

- True/False statements

- Very Short Answer (VSA) questions

- Short Answer (SA) questions

- Long Answer (LA) questions

These papers draw problems from the entire Class 9 mathematics syllabus, reflecting the breadth and depth explored in the preceding NCERT Exemplar chapters. You will find questions testing your understanding of Number Systems, Polynomials, Coordinate Geometry, Linear Equations in Two Variables, Introduction to Euclid's Geometry, Lines and Angles, Triangles, Quadrilaterals, Areas of Parallelograms and Triangles (perhaps requiring application of theorems like $\text{ar}(\triangle) = \frac{1}{2} \text{ar}(\text{gm})$ on the same base and between same parallels), Circles, Constructions, Heron's Formula, Surface Areas and Volumes, Statistics, and Probability.

The provided solutions go beyond just giving the final answer. They serve as a learning tool by explicitly demonstrating the practical application of core concepts, formulas (like Heron's formula $\sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}$), geometric theorems, and effective problem-solving strategies necessary to successfully navigate the varied challenges within each paper. Furthermore, these solutions often highlight how different mathematical topics might be cleverly integrated within a single complex question, offering valuable insights into the interconnectedness of the syllabus. They implicitly guide students on aspects of time management during exams and model the expected standards for clear and logical answer presentation.

By diligently working through these sample papers and then critically reviewing the detailed solutions, students gain a powerful mechanism for self-assessment. This process allows you to effectively gauge your preparation level across the entire curriculum, pinpoint specific areas or topics requiring further attention and practice, and become comfortable with the expected standard of questions, especially those reflecting the Exemplar's focus on application and higher-order thinking. Practicing under simulated exam conditions helps build confidence, while studying the solutions enables refinement of problem-solving techniques and answer-writing strategies. Ultimately, these solved sample papers stand as invaluable resources for final revision cycles, ensuring comprehensive and targeted preparation for your Class 9 examinations.

Section A

In Questions 1 to 10, four options of answer are given in each, out of which only one is correct. Write the correct option.

Question 1. Every rational number is:

(A) a natural number

(B) an integer

(C) a real number

(D) a whole number

Answer:

Solution:

A rational number is defined as any number that can be expressed in the form $p/q$, where $p$ and $q$ are integers and $q \neq 0$. The set of rational numbers is denoted by $\mathbb{Q}$.

Let's examine the definitions of the number sets given in the options:

(A) Natural numbers: The set of natural numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{N}$, consists of positive integers $\{1, 2, 3, ...\}$.

(B) Integers: The set of integers, denoted by $\mathbb{Z}$, consists of all positive and negative whole numbers and zero $\{..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, ...\}$.

(C) Real numbers: The set of real numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{R}$, includes all rational numbers and all irrational numbers (numbers that cannot be expressed as a simple fraction, like $\sqrt{2}$ or $\pi$).

(D) Whole numbers: The set of whole numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{W}$, consists of all non-negative integers $\{0, 1, 2, 3, ...\}$.

Now let's check if every rational number belongs to each of these sets:

Is every rational number a natural number? No. For example, $1/2$ is a rational number, but it is not a natural number.

Is every rational number an integer? No. For example, $1/2$ is a rational number, but it is not an integer.

Is every rational number a whole number? No. For example, $1/2$ is a rational number, but it is not a whole number. Also, negative rational numbers like $-3/4$ are not whole numbers.

Is every rational number a real number? Yes. The set of real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ is the union of the set of rational numbers $\mathbb{Q}$ and the set of irrational numbers $\mathbb{Q}'$. By definition, every rational number is included in the set of real numbers. We can say that $\mathbb{Q} \subseteq \mathbb{R}$.

Therefore, every rational number is a real number.

The correct option is (C) a real number.

Question 2. The distance of point (2, 4) from x-axis is

(A) 2 units

(B) 4 units

(C) 6 units

(D) $\sqrt{2^{2} \;+\; 4^{2}}$ units

Answer:

Solution:

For any point with coordinates $(x, y)$ in the Cartesian plane, its distance from the x-axis is given by the absolute value of its y-coordinate, i.e., $|y|$.

Similarly, its distance from the y-axis is given by the absolute value of its x-coordinate, i.e., $|x|$.

The given point is $(2, 4)$.

Here, the x-coordinate is $x = 2$ and the y-coordinate is $y = 4$.

We need to find the distance of this point from the x-axis.

Using the formula, the distance from the x-axis is $|y|$.

Distance $= |4| = 4$ units.

The correct option is (B) 4 units.

Question 3. The degree of the polynomial (x3 + 7) (3 – x2) is:

(A) 5

(B) 3

(C) 2

(D) –5

Answer:

Solution:

The degree of a polynomial is the highest power of the variable in the polynomial.

When multiplying two polynomials, the degree of the resulting polynomial is the sum of the degrees of the individual polynomials.

The given polynomial is $(x^3 + 7)(3 - x^2)$.

Let $P(x) = x^3 + 7$. The highest power of $x$ is 3. So, the degree of $P(x)$ is 3.

Let $Q(x) = 3 - x^2$. The highest power of $x$ is 2. So, the degree of $Q(x)$ is 2.

The degree of the product polynomial $(x^3 + 7)(3 - x^2)$ is the sum of the degrees of $P(x)$ and $Q(x)$.

Degree of product $= \text{Degree}(P(x)) + \text{Degree}(Q(x))$

Degree of product $= 3 + 2 = 5$.

Alternatively, we can multiply the polynomials:

$(x^3 + 7)(3 - x^2) = x^3(3) + x^3(-x^2) + 7(3) + 7(-x^2)$

$= 3x^3 - x^{3+2} + 21 - 7x^2$

$= 3x^3 - x^5 + 21 - 7x^2$

Rearranging the terms in descending powers of $x$: $-x^5 + 3x^3 - 7x^2 + 21$.

The highest power of $x$ in this polynomial is 5.

So, the degree of the polynomial is 5.

The correct option is (A) 5.

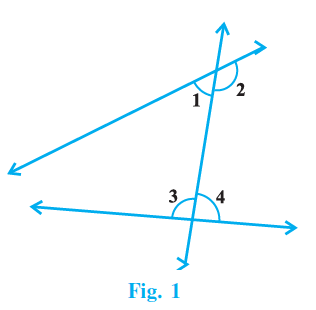

Question 4. In Fig. 1, according to Euclid’s 5th postulate, the pair of angles, having the sum less than 180° is:

(A) 1 and 2

(B) 2 and 4

(C) 1 and 3

(D) 3 and 4

Answer:

Solution:

Euclid's Fifth Postulate states:

"If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side of it taken together less than two right angles ($180^\circ$), then the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the sum of angles is less than two right angles."

In the given figure (Fig. 1), a transversal line intersects two other straight lines. The interior angles on one side of the transversal are labelled as $\angle 1$ and $\angle 2$. The interior angles on the other side are labelled as $\angle 3$ and $\angle 4$.

The figure shows that the two straight lines converge and meet on the side where angles $\angle 1$ and $\angle 2$ are located when extended.

According to Euclid's 5th postulate, if the lines meet on a particular side of the transversal, then the sum of the interior angles on that same side is less than $180^\circ$.

In the figure, the lines meet on the left side of the transversal. The interior angles on the left side are $\angle 1$ and $\angle 2$.

Therefore, according to the postulate, the sum of $\angle 1$ and $\angle 2$ must be less than $180^\circ$.

$\angle 1 + \angle 2 < 180^\circ$

Let's examine the options:

(A) 1 and 2: These are the interior angles on the side where the lines meet. Their sum is less than $180^\circ$ by the postulate.

(B) 2 and 4: These are not interior angles on the same side of the transversal.

(C) 1 and 3: These are vertical angles. Vertical angles are equal ($\angle 1 = \angle 3$), but their sum is not necessarily less than $180^\circ$ in this context.

(D) 3 and 4: These are the interior angles on the side where the lines do not meet (or diverge). If the lines are not parallel, the sum of interior angles on this side will be greater than $180^\circ$.

The pair of angles having the sum less than $180^\circ$ is 1 and 2.

The correct option is (A) 1 and 2.

Question 5. The length of the chord which is at a distance of 12 cm from the centre of a circle of radius 13cm is:

(A) 5 cm

(B) 12 cm

(C) 13 cm

(D) 10 cm

Answer:

Given:

Radius of the circle, $r = 13$ cm.

Distance of the chord from the centre, $d = 12$ cm.

To Find:

The length of the chord.

Solution:

Let the circle have its centre at $O$. Let $AB$ be the chord.

Let $M$ be the midpoint of the chord $AB$. The distance of the chord from the centre is the length of the perpendicular from the centre to the chord.

So, $OM$ is perpendicular to $AB$, and $OM = d = 12$ cm.

The radius of the circle is the distance from the centre to any point on the circle. Let's consider the radius drawn to one end of the chord, say $OA$.

$OA = r = 13$ cm.

In the right-angled triangle $\triangle OMA$ (since $OM \perp AB$), we can use the Pythagorean theorem.

According to the Pythagorean theorem, the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides.

In $\triangle OMA$, the hypotenuse is $OA$ (the radius), and the other two sides are $OM$ (the distance from the centre) and $AM$ (half the length of the chord).

$OA^2 = OM^2 + AM^2$

Substitute the given values:

$13^2 = 12^2 + AM^2$

$169 = 144 + AM^2$

Subtract 144 from both sides to find $AM^2$:

$AM^2 = 169 - 144$

$AM^2 = 25$

Take the square root of both sides to find $AM$:

$AM = \sqrt{25}$

$AM = 5$ cm

The perpendicular from the centre to a chord bisects the chord. This means $M$ is the midpoint of $AB$, so $AM = MB$.

The length of the chord $AB$ is $2 \times AM$.

$AB = 2 \times 5$ cm

$AB = 10$ cm

The length of the chord is 10 cm.

The correct option is (D) 10 cm.

Question 6. If the volume of a sphere is numerically equal to its surface area, then its diameter is:

(A) 2 units

(B) 1 units

(C) 3 units

(D) 6 units

Answer:

Solution:

Let $r$ be the radius of the sphere.

The volume of a sphere is given by the formula $V = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3$.

The surface area of a sphere is given by the formula $SA = 4\pi r^2$.

According to the problem, the volume is numerically equal to the surface area.

$V = SA$

$\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 = 4\pi r^2$

To solve for $r$, we can divide both sides by $4\pi r^2$. We can assume $r \neq 0$ because if $r=0$, both volume and surface area would be 0, which wouldn't be a sphere with a defined diameter in the context of the options.

Divide both sides by $4\pi$:

$\frac{1}{3} r^3 = r^2$

Divide both sides by $r^2$ (assuming $r \neq 0$):

$\frac{1}{3} r = 1$

Multiply both sides by 3:

$r = 3$ units

The diameter of the sphere is $d = 2r$.

$d = 2 \times 3$

$d = 6$ units

The diameter of the sphere is 6 units.

The correct option is (D) 6 units.

Question 7. Two sides of a triangle are 5 cm and 13 cm and its perimeter is 30 cm. The area of the triangle is:

(A) 30 cm2

(B) 60 cm2

(C) 32.5 cm2

(D) 65 cm2

Answer:

Given:

Length of two sides of the triangle are $a = 5$ cm and $b = 13$ cm.

Perimeter of the triangle is 30 cm.

To Find:

The area of the triangle.

Solution:

Let the three sides of the triangle be $a$, $b$, and $c$. We are given $a = 5$ cm and $b = 13$ cm.

The perimeter of a triangle is the sum of the lengths of its three sides.

Perimeter $= a + b + c$

We are given that the perimeter is 30 cm.

$30 = 5 + 13 + c$

$30 = 18 + c$

To find the length of the third side $c$, subtract 18 from both sides:

$c = 30 - 18$

$c = 12$ cm

The lengths of the three sides of the triangle are 5 cm, 13 cm, and 12 cm.

We can calculate the area of the triangle using Heron's formula.

First, calculate the semi-perimeter, $s$, which is half of the perimeter.

$s = \frac{\text{Perimeter}}{2}$

$s = \frac{30}{2}$

$s = 15$ cm

Heron's formula for the area of a triangle with sides $a, b, c$ and semi-perimeter $s$ is:

Area $= \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}$

Substitute the values $s=15$, $a=5$, $b=13$, and $c=12$ into the formula:

Area $= \sqrt{15(15-5)(15-13)(15-12)}$

Area $= \sqrt{15(10)(2)(3)}$

Area $= \sqrt{(3 \times 5) \times (2 \times 5) \times 2 \times 3}$

Group the prime factors:

Area $= \sqrt{(2 \times 2) \times (3 \times 3) \times (5 \times 5)}$

Area $= \sqrt{2^2 \times 3^2 \times 5^2}$

Area $= \sqrt{(2 \times 3 \times 5)^2}$

Area $= 2 \times 3 \times 5$

Area $= 30$ cm$^2$

Alternate Solution:

After finding the sides are 5 cm, 12 cm, and 13 cm, we can check if it is a right-angled triangle using the converse of the Pythagorean theorem. Let the longest side be $c = 13$ cm, and the other two sides be $a = 5$ cm and $b = 12$ cm.

Check if $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$:

$5^2 + 12^2 = 25 + 144 = 169$

$13^2 = 169$

Since $5^2 + 12^2 = 13^2$, the triangle is a right-angled triangle with the sides 5 cm and 12 cm forming the right angle.

The area of a right-angled triangle is $\frac{1}{2} \times \text{base} \times \text{height}$.

Area $= \frac{1}{2} \times 5 \times 12$

Area $= \frac{1}{2} \times 60$

Area $= 30$ cm$^2$

Both methods give the same area, 30 cm$^2$.

The correct option is (A) 30 cm2.

Question 8. Which of the following cannot be the empiral probability of an event

(A) $\frac{2}{3}$

(B) $\frac{3}{2}$

(C) 0

(D) 1

Answer:

Solution:

The empirical probability (also known as experimental probability) of an event is calculated based on the results of an actual experiment or observation.

It is defined as:

Empirical Probability of an event = $\frac{\text{Number of times the event occurred}}{\text{Total number of trials}}$

A fundamental property of probability, whether it is empirical or theoretical, is that its value must lie between 0 and 1, inclusive.

Let $P(E)$ denote the probability of an event $E$. Then, the range of possible values for $P(E)$ is:

$0 \leq P(E) \leq 1$

... (i)

This means that the probability of an event cannot be less than 0 (negative) and cannot be greater than 1.

Let's examine the given options:

(A) $\frac{2}{3}$: This value is approximately 0.667. Since $0 \leq \frac{2}{3} \leq 1$, this can be a probability.

(B) $\frac{3}{2}$: This value is equal to 1.5. Since $1.5 > 1$, this value is outside the possible range for a probability.

(C) 0: This value falls within the range $0 \leq 0 \leq 1$. This can be the probability of an event that did not occur in the experiment.

(D) 1: This value falls within the range $0 \leq 1 \leq 1$. This can be the probability of an event that occurred in every trial of the experiment.

The only value among the options that does not satisfy the condition $0 \leq P(E) \leq 1$ is $\frac{3}{2}$.

Therefore, $\frac{3}{2}$ cannot be the empirical probability of an event.

The correct option is (B) $\frac{3}{2}$.

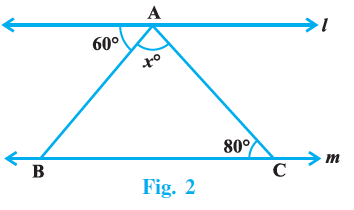

Question 9. In Fig. 2, if l || m , then the value of x is:

(A) 60

(B) 80

(C) 40

(D) 140

Answer:

Solution:

We are given that line $l$ is parallel to line $m$ ($l \parallel m$).

The figure shows a point on line $m$ where two angles, labelled $x$ and $100^\circ$, are adjacent to each other and lie on the straight line $m$. These two angles form a linear pair.

The property of a linear pair is that the sum of the angles is $180^\circ$.

From the figure, the angle marked $x$ and the angle marked $100^\circ$ are adjacent angles on the straight line $m$.

$x + 100^\circ = 180^\circ$

(Angles on a straight line)

To find the value of $x$, subtract $100^\circ$ from both sides of the equation:

$x = 180^\circ - 100^\circ$

$x = 80^\circ$

The value of $x$ is $80^\circ$.

Note: The information about the $40^\circ$ angle and $l \parallel m$ ensures that the geometric configuration shown in the figure, involving a line segment approaching line $m$ at a certain angle, is valid. However, based on the labelling of $x$ and $100^\circ$ as adjacent angles forming a straight line, the value of $x$ is determined directly by their supplementary relationship.

The correct option is (B) 80.

Question 10. The diagonals of a parallelogram :

(A) are equal

(B) bisect each other

(C) are perpendicular to each other

(D) bisect each other at right angles.

Answer:

Solution:

Let's consider the properties of the diagonals of a parallelogram.

A parallelogram is a quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides.

The diagonals of a parallelogram connect opposite vertices.

Consider a general parallelogram ABCD, with diagonals AC and BD intersecting at point O.

Let's evaluate the given options:

(A) are equal: The diagonals of a parallelogram are equal only if the parallelogram is a rectangle or a square. In a general parallelogram that is not a rectangle (e.g., a rhombus that is not a square, or a 'slanted' parallelogram), the diagonals have different lengths.

(B) bisect each other: This is a fundamental property of all parallelograms. The diagonals of a parallelogram intersect at their midpoint. This means that the point of intersection divides each diagonal into two equal parts (i.e., $AO = OC$ and $BO = OD$).

(C) are perpendicular to each other: The diagonals of a parallelogram are perpendicular to each other only if the parallelogram is a rhombus or a square. In a general parallelogram that is not a rhombus, the diagonals are not perpendicular.

(D) bisect each other at right angles: This is a combination of options (B) and (C). The diagonals bisect each other *and* are perpendicular only if the parallelogram is a rhombus or a square. This is not true for a general parallelogram (e.g., a rectangle that is not a square).

The property that holds true for every parallelogram is that its diagonals bisect each other.

The correct option is (B) bisect each other.

Section B

Question 11. Is – 5 a rational number? Give reasons to your answer.

Answer:

Solution:

Yes, – 5 is a rational number.

Reason:

A number is defined as a rational number if it can be expressed in the form $\frac{p}{q}$, where $p$ and $q$ are integers and $q \neq 0$.

The number – 5 can be written as a fraction in the form $\frac{p}{q}$ as follows:

$-5 = \frac{-5}{1}$

In this representation, $p = -5$ and $q = 1$.

Both $p = -5$ and $q = 1$ are integers.

Also, the denominator $q = 1$, which is not equal to zero ($q \neq 0$).

Since – 5 can be expressed in the form $\frac{p}{q}$ where $p, q \in \mathbb{Z}$ and $q \neq 0$, it satisfies the definition of a rational number.

In fact, every integer is a rational number because any integer $n$ can be written as $\frac{n}{1}$.

Question 12. Without actually finding p(5), find whether (x–5) is a factor of p (x) = x3 – 7x2 + 16x – 12. Justify your answer.

Answer:

Solution:

We are asked to determine if $(x-5)$ is a factor of the polynomial $p(x) = x^3 - 7x^2 + 16x - 12$ without directly calculating the value of $p(5)$.

We can use the Factor Theorem to solve this problem.

Factor Theorem:

The Factor Theorem states that for a polynomial $p(x)$, $(x-a)$ is a factor of $p(x)$ if and only if $p(a) = 0$.

In this case, the potential factor is $(x-5)$, which is of the form $(x-a)$ with $a = 5$.

According to the Factor Theorem, $(x-5)$ is a factor of $p(x)$ if and only if $p(5) = 0$.

To find the value of $p(5)$ without direct substitution $5^3 - 7(5^2) + 16(5) - 12$, we can use the Remainder Theorem, which is closely related to the Factor Theorem.

Remainder Theorem:

The Remainder Theorem states that when a polynomial $p(x)$ is divided by $(x-a)$, the remainder is $p(a)$.

So, we can divide the polynomial $p(x) = x^3 - 7x^2 + 16x - 12$ by $(x-5)$ and find the remainder. The remainder will be equal to $p(5)$. If the remainder is 0, then $(x-5)$ is a factor.

We can use synthetic division for this purpose.

The coefficients of the polynomial $p(x) = 1 \cdot x^3 + (-7) \cdot x^2 + 16 \cdot x + (-12)$ are 1, -7, 16, and -12.

We are dividing by $(x-5)$, so we use $a=5$ for synthetic division.

Performing synthetic division:

$\begin{array}{c|cccc} 5 & 1 & -7 & 16 & -12 \\ & & 5 & -10 & 30 \\ \hline & 1 & -2 & 6 & 18 \end{array}$

The numbers in the last row are the coefficients of the quotient and the remainder. The last number in the last row is the remainder.

The remainder is 18.

According to the Remainder Theorem, the remainder is equal to $p(5)$.

Remainder = $p(5)$

$p(5) = 18$

According to the Factor Theorem, $(x-5)$ is a factor of $p(x)$ if and only if $p(5) = 0$.

Since $p(5) = 18$, which is not equal to 0 ($18 \neq 0$), $(x-5)$ is not a factor of $p(x)$.

Justification:

By the Factor Theorem, $(x-5)$ is a factor of the polynomial $p(x)$ if and only if $p(5) = 0$. We used synthetic division to find the remainder when $p(x)$ is divided by $(x-5)$. The remainder is equal to $p(5)$ by the Remainder Theorem. The remainder found was 18. Since the remainder, $p(5)$, is not 0, $(x-5)$ is not a factor of $p(x)$.

Question 13. Is (1, 8) the only solution of y = 3x + 5? Give reasons.

Answer:

Solution:

No, (1, 8) is not the only solution of the equation $y = 3x + 5$.

Reason:

First, let's verify that (1, 8) is indeed a solution. Substitute $x=1$ and $y=8$ into the equation:

$8 = 3(1) + 5$

$8 = 3 + 5$

$8 = 8$

Since the equation is satisfied, (1, 8) is a solution.

The equation $y = 3x + 5$ is a linear equation in two variables ($x$ and $y$). A linear equation in two variables represents a straight line in the Cartesian coordinate system.

A straight line consists of infinitely many points, and each point on the line corresponds to a unique solution $(x, y)$ of the equation.

For example, we can find other solutions by choosing different values for $x$ and calculating the corresponding values for $y$:

If $x = 0$, then $y = 3(0) + 5 = 0 + 5 = 5$. So, (0, 5) is a solution.

If $x = -1$, then $y = 3(-1) + 5 = -3 + 5 = 2$. So, (-1, 2) is a solution.

If $x = 2$, then $y = 3(2) + 5 = 6 + 5 = 11$. So, (2, 11) is a solution.

Since there are infinitely many possible values for $x$ (and consequently for $y$), there are infinitely many solutions to the equation $y = 3x + 5$.

Therefore, (1, 8) is just one of the infinitely many solutions to the equation.

Question 14. Write the coordinates of a point on x-axis at a distance of 4 units from origin in the positive direction of x-axis and then justify your answer.

Answer:

Solution:

The coordinates of a point on the x-axis at a distance of 4 units from the origin in the positive direction of the x-axis are (4, 0).

Justification:

In the Cartesian coordinate system, points are represented by ordered pairs $(x, y)$, where $x$ is the x-coordinate and $y$ is the y-coordinate.

Points that lie on the x-axis have their y-coordinate equal to 0. So, the coordinates of any point on the x-axis are of the form $(x, 0)$.

The origin is the point where the x-axis and y-axis intersect, and its coordinates are (0, 0).

The distance of a point $(x, 0)$ on the x-axis from the origin $(0, 0)$ is given by the absolute value of its x-coordinate, $|x|$.

We are given that the distance of the point from the origin is 4 units.

So, $|x| = 4$. This means $x = 4$ or $x = -4$.

We are also given that the point is in the positive direction of the x-axis. The positive direction of the x-axis is to the right of the origin, where the x-coordinates are positive.

Therefore, we must choose the positive value for $x$, which is $x = 4$.

Since the point is on the x-axis, its y-coordinate is 0.

Thus, the coordinates of the point are $(4, 0)$.

Question 15. Two coins are tossed simultaneously 500 times. If we get two heads 100 times, one head 270 times and no head 130 times, then find the probability of getting one or more than one head. Give reasons to your answer also.

Answer:

Given:

Total number of times two coins are tossed = 500.

Number of times two heads (HH) are obtained = 100.

Number of times one head (HT or TH) is obtained = 270.

Number of times no head (TT) is obtained = 130.

To Find:

The probability of getting one or more than one head.

Solution:

Let $E$ be the event of getting one or more than one head.

Getting "one or more than one head" means getting either one head or two heads.

The number of times the event $E$ occurred is the sum of the number of times we got one head and the number of times we got two heads.

Number of times event $E$ occurred = (Number of times one head) + (Number of times two heads)

Number of times event $E$ occurred = $270 + 100 = 370$.

The total number of trials is 500.

The empirical probability of an event is given by the formula:

$P(E) = \frac{\text{Number of times the event occurred}}{\text{Total number of trials}}$

Substitute the values:

$P(\text{one or more heads}) = \frac{370}{500}$

Simplify the fraction by dividing the numerator and the denominator by 10:

$P(\text{one or more heads}) = \frac{37}{50}$

The probability of getting one or more than one head is $\frac{37}{50}$.

Reason:

The probability calculated here is an empirical probability because it is based on the results of an actual experiment (tossing two coins 500 times). The empirical probability of an event is the ratio of the number of times the event happens to the total number of trials conducted in the experiment. In this case, the event "getting one or more than one head" occurred 370 times out of 500 total tosses, leading to a probability of $\frac{370}{500} = \frac{37}{50}$.

Section C

Question 16. Simplify the following expression

($\sqrt{3}$ + 1) (1 - $\sqrt{12}$) + $\frac{9}{\sqrt{3} \;+\; \sqrt{12}}$

OR

Express 0.12$\overline{3}$ in the form of $\frac{p}{q}$ q ≠ 0, p and q are integers.

Answer:

Solution:

We are asked to simplify the expression $(\sqrt{3} + 1)(1 - \sqrt{12}) + \frac{9}{\sqrt{3} \;+\; \sqrt{12}}$.

First, simplify $\sqrt{12}$:

$\sqrt{12} = \sqrt{4 \times 3} = \sqrt{4} \times \sqrt{3} = 2\sqrt{3}$

Substitute this back into the expression:

$(\sqrt{3} + 1)(1 - 2\sqrt{3}) + \frac{9}{\sqrt{3} \;+\; 2\sqrt{3}}$

Simplify the sum in the denominator of the fraction:

$\sqrt{3} + 2\sqrt{3} = (1+2)\sqrt{3} = 3\sqrt{3}$

The expression becomes:

$(\sqrt{3} + 1)(1 - 2\sqrt{3}) + \frac{9}{3\sqrt{3}}$

Simplify the fraction $\frac{9}{3\sqrt{3}}$:

$\frac{\cancel{9}^{3}}{\cancel{3}_{1}\sqrt{3}} = \frac{3}{\sqrt{3}}$

To rationalize the denominator, multiply the numerator and denominator by $\sqrt{3}$:

$\frac{3}{\sqrt{3}} \times \frac{\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{3}} = \frac{3\sqrt{3}}{3} = \sqrt{3}$

The expression is now:

$(\sqrt{3} + 1)(1 - 2\sqrt{3}) + \sqrt{3}$

Expand the product $(\sqrt{3} + 1)(1 - 2\sqrt{3})$ using the distributive property (FOIL method):

$(\sqrt{3})(1) + (\sqrt{3})(-2\sqrt{3}) + (1)(1) + (1)(-2\sqrt{3})$

$= \sqrt{3} - 2(\sqrt{3} \times \sqrt{3}) + 1 - 2\sqrt{3}$

$= \sqrt{3} - 2(3) + 1 - 2\sqrt{3}$

$= \sqrt{3} - 6 + 1 - 2\sqrt{3}$

Combine the like terms ($\sqrt{3}$ terms and constant terms):

$(\sqrt{3} - 2\sqrt{3}) + (-6 + 1)$

$= (1 - 2)\sqrt{3} - 5$

$= -\sqrt{3} - 5$

Now, add the simplified fraction term ($\sqrt{3}$) to this result:

$(-\sqrt{3} - 5) + \sqrt{3}$

$= -\sqrt{3} - 5 + \sqrt{3}$

$= (-\sqrt{3} + \sqrt{3}) - 5$

$= 0 - 5$

$= -5$

The simplified value of the expression is -5.

Alternate Solution:

We are asked to express $0.12\overline{3}$ in the form $\frac{p}{q}$.

Let $x = 0.12\overline{3}$.

$x = 0.12333...$

Multiply by 100 to move the decimal point past the non-repeating part (0.12):

$100x = 12.333...$

... (i)

The repeating part is '3', which has 1 digit. Multiply equation (i) by $10^1 = 10$ to move the decimal point one place to the right, past one cycle of the repeating digit:

$10 \times (100x) = 10 \times (12.333...)$

$1000x = 123.333...$

... (ii)

Subtract equation (i) from equation (ii) to eliminate the repeating part:

$1000x - 100x = 123.333... - 12.333...$

$900x = 111$

Solve for $x$:

$x = \frac{111}{900}$

Simplify the fraction $\frac{111}{900}$. Both the numerator and the denominator are divisible by 3 (since the sum of digits of 111 is $1+1+1=3$, and the sum of digits of 900 is $9+0+0=9$).

$\frac{\cancel{111}^{37}}{\cancel{900}_{300}}$

$x = \frac{37}{300}$

The number $0.12\overline{3}$ expressed in the form $\frac{p}{q}$ is $\frac{37}{300}$, where $p=37$ and $q=300$ are integers and $q \neq 0$.

Question 17. Verify that:

x3 + y3 + z3 - 3xyz $\frac{1}{2}$ (x + y + z) [(x - y)2 + (y - z)2 + (z - x)2 ]

Answer:

Solution:

We need to verify the identity:

$x^3 + y^3 + z^3 - 3xyz = \frac{1}{2}(x + y + z)[(x - y)^2 + (y - z)^2 + (z - x)^2]$

Let's start with the Right Hand Side (RHS) of the identity and simplify it:

RHS $= \frac{1}{2}(x + y + z)[(x - y)^2 + (y - z)^2 + (z - x)^2]$

First, expand the squared terms inside the square bracket using the identity $(a-b)^2 = a^2 - 2ab + b^2$:

$(x - y)^2 = x^2 - 2xy + y^2$

$(y - z)^2 = y^2 - 2yz + z^2$}

$(z - x)^2 = z^2 - 2zx + x^2$

Now substitute these expansions back into the square bracket:

$(x - y)^2 + (y - z)^2 + (z - x)^2 = (x^2 - 2xy + y^2) + (y^2 - 2yz + z^2) + (z^2 - 2zx + x^2)$

Combine the like terms ($x^2, y^2, z^2, xy, yz, zx$):

$= x^2 + x^2 + y^2 + y^2 + z^2 + z^2 - 2xy - 2yz - 2zx$

$= 2x^2 + 2y^2 + 2z^2 - 2xy - 2yz - 2zx$

Factor out 2 from the expression:

$= 2(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - xy - yz - zx)$

Now substitute this back into the RHS expression:

RHS $= \frac{1}{2}(x + y + z)[2(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - xy - yz - zx)]$}

Cancel out the $\frac{1}{2}$ and 2:

RHS $= (x + y + z)(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - xy - yz - zx)$

Now expand this product. Multiply each term in the first parenthesis by each term in the second parenthesis:

RHS $= x(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - xy - yz - zx) + y(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - xy - yz - zx) + z(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - xy - yz - zx)$

RHS $= (x^3 + xy^2 + xz^2 - x^2y - xyz - x^2z) + (yx^2 + y^3 + yz^2 - xy^2 - y^2z - xyz) + (zx^2 + zy^2 + z^3 - xyz - yz^2 - z^2x)$

Combine and cancel terms:

RHS $= x^3 + y^3 + z^3 + (xy^2 - xy^2) + (xz^2 - xz^2) + (-x^2y + yx^2) + (-x^2z + zx^2) + (yz^2 - yz^2) + (-y^2z + zy^2) + (-xyz - xyz - xyz)

RHS $= x^3 + y^3 + z^3 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 - 3xyz$

RHS $= x^3 + y^3 + z^3 - 3xyz$

This is equal to the Left Hand Side (LHS) of the identity.

LHS $= x^3 + y^3 + z^3 - 3xyz$

Since LHS = RHS, the identity is verified.

Question 18. Find the value of k, if (x – 2) is a factor of 4x3 + 3x2 – 4x + k.

Answer:

Given:

The polynomial is $p(x) = 4x^3 + 3x^2 - 4x + k$.

$(x-2)$ is a factor of $p(x)$.

To Find:

The value of $k$.

Solution:

We can use the Factor Theorem to find the value of $k$.

The Factor Theorem states that if $(x-a)$ is a factor of a polynomial $p(x)$, then $p(a) = 0$.

In this problem, the factor is $(x-2)$, so $a=2$.

According to the Factor Theorem, since $(x-2)$ is a factor of $p(x)$, we must have $p(2) = 0$.

Substitute $x=2$ into the polynomial $p(x) = 4x^3 + 3x^2 - 4x + k$:

$p(2) = 4(2)^3 + 3(2)^2 - 4(2) + k$

Calculate the terms:

$2^3 = 2 \times 2 \times 2 = 8$

$2^2 = 2 \times 2 = 4$

Substitute these values back into the expression for $p(2)$:

$p(2) = 4(8) + 3(4) - 4(2) + k$

$p(2) = 32 + 12 - 8 + k$}

Perform the arithmetic operations:

$p(2) = (32 + 12) - 8 + k$

$p(2) = 44 - 8 + k$}

$p(2) = 36 + k$}

Since $(x-2)$ is a factor, we set $p(2) = 0$:

$36 + k = 0$

Solve for $k$ by subtracting 36 from both sides:

$k = -36$

The value of $k$ is -36.

Question 19. Write the quadrant in which each of the following points lie :

(i) (–3, –5)

(ii) (2, –5)

(iii) (–3, 5)

Also, verify by locating them on the cartesian plane.

Answer:

Solution:

The Cartesian plane is divided into four quadrants by the x-axis and the y-axis. The quadrant in which a point $(x, y)$ lies depends on the signs of its coordinates $x$ and $y$.

Quadrant I: $x > 0$, $y > 0$ (positive x, positive y)

Quadrant II: $x < 0$, $y > 0$ (negative x, positive y)

Quadrant III: $x < 0$, $y < 0$ (negative x, negative y)

Quadrant IV: $x > 0$, $y < 0$ (positive x, negative y)

Now let's determine the quadrant for each given point based on the signs of its coordinates:

(i) Point (–3, –5):

The x-coordinate is -3, which is negative ($x < 0$).

The y-coordinate is -5, which is negative ($y < 0$).

Since both the x-coordinate and the y-coordinate are negative, the point (–3, –5) lies in Quadrant III.

(ii) Point (2, –5):

The x-coordinate is 2, which is positive ($x > 0$).

The y-coordinate is -5, which is negative ($y < 0$).

Since the x-coordinate is positive and the y-coordinate is negative, the point (2, –5) lies in Quadrant IV.

(iii) Point (–3, 5):

The x-coordinate is -3, which is negative ($x < 0$).

The y-coordinate is 5, which is positive ($y > 0$).

Since the x-coordinate is negative and the y-coordinate is positive, the point (–3, 5) lies in Quadrant II.

Verification by locating on the Cartesian plane:

To locate a point $(x, y)$ on the Cartesian plane, start at the origin (0, 0). Move $|x|$ units horizontally along the x-axis (right if $x > 0$, left if $x < 0$). From there, move $|y|$ units vertically parallel to the y-axis (up if $y > 0$, down if $y < 0$).

(i) For (–3, –5): Start at (0,0). Move 3 units to the left along the x-axis (since x is -3). From there, move 5 units down parallel to the y-axis (since y is -5). The region that is to the left of the y-axis and below the x-axis is Quadrant III. This confirms that (–3, –5) lies in Quadrant III.

(ii) For (2, –5): Start at (0,0). Move 2 units to the right along the x-axis (since x is 2). From there, move 5 units down parallel to the y-axis (since y is -5). The region that is to the right of the y-axis and below the x-axis is Quadrant IV. This confirms that (2, –5) lies in Quadrant IV.

(iii) For (–3, 5): Start at (0,0). Move 3 units to the left along the x-axis (since x is -3). From there, move 5 units up parallel to the y-axis (since y is 5). The region that is to the left of the y-axis and above the x-axis is Quadrant II. This confirms that (–3, 5) lies in Quadrant II.

The locations determined by plotting on the Cartesian plane match the quadrants identified based on the signs of the coordinates.

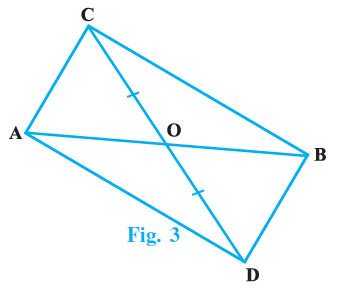

Question 20. In Figure 3, ABC and ABD are two triangles on the same base AB.

If the line segment CD is bisected by AB at O, then show that: area (∆ABC) = area (∆ABD)

Answer:

Given:

ABC and ABD are two triangles on the same base AB.

The line segment CD is bisected by the line AB at point O.

To Prove:

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABC}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{ABD})$

Proof:

We are given that the line segment CD is bisected by the line AB at point O. This means that O is the point of intersection of AB and CD, and O is the midpoint of the line segment CD.

CO = OD

(Since O is the midpoint of CD)

Consider $\triangle \text{ACD}$. The point O is the midpoint of the side CD. The line segment AO connects the vertex A to the midpoint O of the opposite side CD. Thus, AO is a median of $\triangle \text{ACD}$.

We know that a median of a triangle divides it into two triangles of equal areas.

Therefore, the median AO divides $\triangle \text{ACD}$ into two triangles, $\triangle \text{AOC}$ and $\triangle \text{AOD}$, such that their areas are equal.

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{AOC}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{AOD})$

... (1)

Now consider $\triangle \text{BCD}$. The point O is the midpoint of the side CD. The line segment BO connects the vertex B to the midpoint O of the opposite side CD. Thus, BO is a median of $\triangle \text{BCD}$.

The median BO divides $\triangle \text{BCD}$ into two triangles, $\triangle \text{BOC}$ and $\triangle \text{BOD}$, such that their areas are equal.

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{BOC}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{BOD})$

... (2)

Now, consider the area of $\triangle \text{ABC}$. From the figure, $\triangle \text{ABC}$ is composed of two smaller triangles, $\triangle \text{AOC}$ and $\triangle \text{BOC}$.

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABC}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{AOC}) + \text{area}(\triangle \text{BOC})$

Similarly, consider the area of $\triangle \text{ABD}$. From the figure, $\triangle \text{ABD}$ is composed of two smaller triangles, $\triangle \text{AOD}$ and $\triangle \text{BOD}$.

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABD}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{AOD}) + \text{area}(\triangle \text{BOD})$

Now, substitute the equalities from equations (1) and (2) into the expression for $\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABC})$:

From (1), replace $\text{area}(\triangle \text{AOC})$ with $\text{area}(\triangle \text{AOD})$.

From (2), replace $\text{area}(\triangle \text{BOC})$ with $\text{area}(\triangle \text{BOD})$.

So,

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABC}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{AOD}) + \text{area}(\triangle \text{BOD})$

Comparing this expression with the expression for $\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABD})$, we see that they are the same.

Therefore,

$\text{area}(\triangle \text{ABC}) = \text{area}(\triangle \text{ABD})$

Hence, proved.

Question 21. Solve the equation 3x + 2 = 2x – 2 and represent the solution on the cartesian plane.

Answer:

Solution:

First, let's solve the given linear equation in one variable:

$3x + 2 = 2x - 2$

Subtract $2x$ from both sides of the equation:

$3x - 2x + 2 = 2x - 2x - 2$

$x + 2 = -2$

Subtract 2 from both sides of the equation:

$x + 2 - 2 = -2 - 2$

$x = -4$

The solution to the equation $3x + 2 = 2x - 2$ is $x = -4$.

Now, we need to represent this solution on the Cartesian plane.

The Cartesian plane uses two axes, the x-axis and the y-axis, to plot points $(x, y)$.

The solution $x = -4$ is an equation in one variable. When representing such an equation on a 2D Cartesian plane, it represents a set of points $(x, y)$ where the x-coordinate is always -4, and the y-coordinate can be any real number.

This can be thought of as a linear equation in two variables: $x + 0 \cdot y = -4$.

This equation means that for any value of $y$, $x$ is always -4.

Examples of points that satisfy this equation are:

$(-4, 0)$ (when $y=0$)

$(-4, 1)$ (when $y=1$)

$(-4, -2)$ (when $y=-2$)

and so on.

The set of all points where the x-coordinate is constant ($x=-4$) forms a vertical line that is parallel to the y-axis and passes through the point $(-4, 0)$ on the x-axis.

To represent this solution on the Cartesian plane, draw the x and y axes. Locate the point where $x = -4$ on the x-axis. Then, draw a vertical line passing through this point. This line represents all the points $(x, y)$ where $x = -4$, and thus is the graphical representation of the solution $x = -4$ on the Cartesian plane.

Question 22. Construct a right triangle whose base is 12 cm and the difference in lengths of its hypotenuse and the other side is 8cm. Also give justification of the steps of construction.

Answer:

Given:

Base of a right triangle = 12 cm.

Difference between the lengths of the hypotenuse and the other side = 8 cm.

Construction Required:

To construct the right triangle.

Steps of Construction:

1. Draw a line segment BC of length 12 cm. This will be the base of the triangle.

2. At point B, construct a ray BX perpendicular to BC. This ray will contain the side AB of the right triangle, since the triangle is right-angled at B.

3. Extend the ray XB in the opposite direction to form ray BY.

4. On the ray BY, mark a point D such that BD = 8 cm (the given difference between the hypotenuse and the other side).

5. Join CD.

6. Construct the perpendicular bisector of the line segment CD. To do this, place the compass at C and D with a radius greater than half of CD, and draw arcs intersecting on both sides of CD. Join the points of intersection of the arcs to get the perpendicular bisector.

7. Let the perpendicular bisector intersect the ray BX at point A.

8. Join AC.

9. $\triangle$ABC is the required right triangle.

Justification of Construction:

We need to justify that $\triangle$ABC is a right triangle with base BC = 12 cm and $AC - AB = 8$ cm.

1. By construction, BC = 12 cm.

2. By construction, the ray BX is perpendicular to BC at B. Therefore, $\angle$ABC = $90^\circ$. This confirms that $\triangle$ABC is a right triangle with the right angle at B and base BC.

3. By construction, point A lies on the perpendicular bisector of the line segment CD. A fundamental property of a perpendicular bisector is that any point on it is equidistant from the endpoints of the segment it bisects.

Therefore, AC = AD.

AC = AD

(Property of perpendicular bisector)

4. By construction, D is marked on the ray BY, which is the extension of XB beyond B. Point A lies on the ray BX. This means the points D, B, and A are collinear, with B lying between D and A.

The distance AD is the sum of the distances AB and BD.

AD = AB + BD

5. Substitute the value of BD = 8 cm (by construction) and AD = AC (from step 3) into the equation AD = AB + BD:

AC = AB + 8

Rearranging this equation, we get:

AC - AB = 8

This shows that the difference between the hypotenuse AC and the other side AB is 8 cm, which matches the given condition.

Thus, $\triangle$ABC is a right triangle with base BC = 12 cm and the difference between the lengths of its hypotenuse (AC) and the other side (AB) is 8 cm. The construction is justified.

Question 23. In a quadrilateral ABCD, AB = 9 cm, BC = 12 cm, CD = 5 cm, AD = 8 cm and ∠C = 90°. Find the area of ∆ABD

Answer:

Given:

A quadrilateral ABCD with sides AB = 9 cm, BC = 12 cm, CD = 5 cm, AD = 8 cm.

Angle $\angle$C = $90^\circ$.

To Find:

The area of $\triangle$ABD.

Solution:

The quadrilateral ABCD is divided into two triangles by the diagonal BD: $\triangle$BCD and $\triangle$ABD.

We are given that $\angle$C = $90^\circ$, so $\triangle$BCD is a right-angled triangle with the right angle at C.

In the right-angled $\triangle$BCD, BC is the base and CD is the height (or vice-versa).

First, let's find the length of the diagonal BD using the Pythagorean theorem in $\triangle$BCD.

In $\triangle$BCD, the hypotenuse is BD, and the other two sides are BC and CD.

$BD^2 = BC^2 + CD^2$

Substitute the given lengths BC = 12 cm and CD = 5 cm:

$BD^2 = (12)^2 + (5)^2$

$BD^2 = 144 + 25$

$BD^2 = 169$

Take the square root of both sides to find BD:

$BD = \sqrt{169}$

$BD = 13$ cm

Now consider $\triangle$ABD. We know the lengths of all three sides of this triangle:

AB = 9 cm (Given)

AD = 8 cm (Given)

BD = 13 cm (Calculated)

We can find the area of $\triangle$ABD using Heron's formula. First, calculate the semi-perimeter $s$ of $\triangle$ABD.

$s = \frac{AB + AD + BD}{2}$

$s = \frac{9 + 8 + 13}{2}$

$s = \frac{30}{2}$

$s = 15$ cm

Heron's formula for the area of a triangle with sides $a, b, c$ and semi-perimeter $s$ is:

Area $= \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}$

For $\triangle$ABD, let $a=AB=9$, $b=AD=8$, and $c=BD=13$. The semi-perimeter is $s=15$.

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = \sqrt{15(15-9)(15-8)(15-13)}$

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = \sqrt{15(6)(7)(2)}$

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = \sqrt{(3 \times 5) \times (2 \times 3) \times 7 \times 2}$

Group the prime factors:

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = \sqrt{(2 \times 2) \times (3 \times 3) \times 5 \times 7}$

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = \sqrt{2^2 \times 3^2 \times 35}$

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = \sqrt{(2 \times 3)^2 \times 35}$

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = 2 \times 3 \sqrt{35}$

Area$(\triangle$ABD$) = 6\sqrt{35}$ cm$^2$

The area of $\triangle$ABD is $6\sqrt{35}$ cm$^2$.

Note: The area of the quadrilateral ABCD would be the sum of the areas of $\triangle$BCD and $\triangle$ABD. The area of $\triangle$BCD is $\frac{1}{2} \times \text{BC} \times \text{CD} = \frac{1}{2} \times 12 \times 5 = 30$ cm$^2$. The total area of the quadrilateral is $30 + 6\sqrt{35}$ cm$^2$. The question specifically asks only for the area of $\triangle$ABD.

Question 24. In a hot water heating system, there is a cylindrical pipe of length 35 m and diameter 10 cm. Find the total radiating surface in the system.

OR

The floor of a rectangular hall has a perimeter 150 m. If the cost of painting the four walls at the rate of Rs 10 per m2 is Rs 9000, find the height of the hall.

Answer:

Solution (for the first part of the question):

Given:

Length of the cylindrical pipe, $h = 35$ m.

Diameter of the pipe, $d = 10$ cm.

To Find:

The total radiating surface of the pipe.

Solution:

The radiating surface of a cylindrical pipe is its lateral surface area.

The formula for the lateral surface area of a cylinder is $2\pi rh$, where $r$ is the radius and $h$ is the height (or length in this case) of the cylinder.

First, we need to find the radius from the given diameter. The radius is half of the diameter.

Radius, $r = \frac{\text{Diameter}}{2} = \frac{10 \text{ cm}}{2} = 5$ cm.

The length of the pipe is given in meters, so we should convert the radius from centimeters to meters to maintain consistent units. We know that 1 meter = 100 centimeters.

$r = 5 \text{ cm} = \frac{5}{100} \text{ m} = 0.05$ m.

Now, substitute the values of $r$ and $h$ into the formula for the lateral surface area:

Lateral Surface Area $= 2\pi rh$

Lateral Surface Area $= 2 \times \pi \times 0.05 \text{ m} \times 35 \text{ m}$

Lateral Surface Area $= 2 \times 0.05 \times 35 \times \pi \text{ m}^2$

Lateral Surface Area $= 0.10 \times 35 \times \pi \text{ m}^2$

Lateral Surface Area $= 3.5 \times \pi \text{ m}^2$

Using the approximation $\pi \approx \frac{2\cancel{2}}{7}$ or $\pi \approx 3.14$:

Lateral Surface Area $\approx 3.5 \times \frac{22}{7} \text{ m}^2$

Lateral Surface Area $\approx \frac{\cancel{3.5}^{0.5}}{\cancel{7}_{1}} \times 22 \text{ m}^2$

Lateral Surface Area $\approx 0.5 \times 22 \text{ m}^2$

Lateral Surface Area $\approx 11 \text{ m}^2$

The total radiating surface in the system is approximately 11 m$^2$.

(If $\pi$ is kept as $\pi$, the answer is $3.5\pi$ m$^2$. Using $\pi \approx 3.14$, Area $\approx 3.5 \times 3.14 = 10.99$ m$^2$, which is close to 11 m$^2$). Assuming $\pi = \frac{22}{7}$ is expected for a cleaner number.

The total radiating surface in the system is 11 m$^2$.

Question 25. Three coins are tossed simultaneously 200 times with the following frequencies of different outcomes:

| Outcome | 3 tails | 2 tails | 1 tail | no tail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 20 | 68 | 82 | 30 |

If the three coins are simultaneously tossed again, compute the probability of getting less than 3 tails.

Answer:

Given:

Total number of times three coins are tossed = 200.

The frequencies of the outcomes are provided in the table:

| Outcome | 3 tails | 2 tails | 1 tail | no tail |

| Frequency | 20 | 68 | 82 | 30 |

To Compute:

The probability of getting less than 3 tails.

Solution:

The event "getting less than 3 tails" includes the outcomes where we get 0 tails, 1 tail, or 2 tails.

From the given table, the frequencies of these outcomes are:

Frequency of 0 tails (no tail) = 30

Frequency of 1 tail = 82

Frequency of 2 tails = 68

The number of times the event "getting less than 3 tails" occurred is the sum of the frequencies of these outcomes:

Number of outcomes with less than 3 tails = (Frequency of 0 tails) + (Frequency of 1 tail) + (Frequency of 2 tails)

Number of outcomes with less than 3 tails = $30 + 82 + 68$

Number of outcomes with less than 3 tails = $112 + 68 = 180$.

The total number of trials is given as 200.

The empirical probability of an event is given by:

$P(\text{Event}) = \frac{\text{Number of times the event occurred}}{\text{Total number of trials}}$

The probability of getting less than 3 tails is:

$P(\text{less than 3 tails}) = \frac{\text{Number of outcomes with less than 3 tails}}{\text{Total number of trials}}$

$P(\text{less than 3 tails}) = \frac{180}{200}$

Simplify the fraction:

$P(\text{less than 3 tails}) = \frac{\cancel{180}^{18}}{\cancel{200}_{20}} = \frac{\cancel{18}^{9}}{\cancel{20}_{10}} = \frac{9}{10}$

The probability of getting less than 3 tails is $\frac{9}{10}$.

Section D

Question 26. The taxi fair in a city is as follows:

For the first kilometer, the fare is Rs 10 and for the subsequent distance it is Rs 6 per km. Taking the distance covered as x km and total fare as Rs y, write a linear equation for this information and draw its graph.

From the graph, find the fare for travelling a distance of 4 km.

Answer:

Solution:

Let the total distance covered be $x$ km and the total fare be $\textsf{₹}y$.

According to the given information:

The fare for the first kilometer is $\textsf{₹}10$.

For the subsequent distance (distance after the first km), the fare is $\textsf{₹}6$ per km.

If the total distance covered is $x$ km, where $x \geq 1$ km, the distance can be considered in two parts:

1. The first kilometer, for which the fare is fixed at $\textsf{₹}10$.

2. The remaining distance, which is the total distance minus the first kilometer, i.e., $(x - 1)$ km. The fare for this subsequent distance is $\textsf{₹}6$ per km.

The total fare $y$ is the sum of the fare for the first kilometer and the fare for the remaining distance.

Total Fare ($y$) = Fare for 1st km + Fare for subsequent distance

$y = 10 + (\text{subsequent distance in km}) \times 6$

For $x \geq 1$, the subsequent distance is $(x-1)$ km.

$y = 10 + (x-1) \times 6$

Simplify the equation to write it in the form of a linear equation:

$y = 10 + 6x - 6$

y = 6x + 4

... (1)

This is the linear equation representing the total fare $y$ for a distance of $x$ km, particularly relevant for $x \geq 1$. The graph of this linear equation is a straight line.

Drawing the graph:

To draw the graph of the linear equation $y = 6x + 4$, we need to plot at least two points that lie on this line. Since distance $x$ must be non-negative, we consider values of $x \geq 0$. Let's choose a few values for $x$ and find the corresponding values for $y$ using Equation (1).

| x (Distance in km) | y = 6x + 4 (Fare in $\textsf{₹}$) | Point (x, y) |

| 0 | $y = 6(0) + 4 = 4$ | (0, 4) |

| 1 | $y = 6(1) + 4 = 10$ | (1, 10) |

| 2 | $y = 6(2) + 4 = 16$ | (2, 16) |

| 3 | $y = 6(3) + 4 = 22$ | (3, 22) |

To draw the graph of $y = 6x + 4$:

1. Draw two perpendicular lines, the x-axis and the y-axis, on a graph paper. Their intersection is the origin (0, 0).

2. Label the x-axis as 'Distance (km)' and the y-axis as 'Total Fare ($\textsf{₹}$)'.

3. Choose appropriate scales for both axes. For instance, you could take 1 cm = 1 km on the x-axis and 1 cm = $\textsf{₹}5$ or $\textsf{₹}10$ on the y-axis.

4. Plot at least two of the points found above, for example, (0, 4) and (1, 10).

5. Draw a straight line that passes through the plotted points. This line represents the graph of the equation $y = 6x + 4$. Since distance ($x$) cannot be negative, the graph is relevant for $x \geq 0$.

Finding the fare for travelling a distance of 4 km from the graph:

To find the fare for a distance of 4 km from the graph, locate the value $x = 4$ on the x-axis.

Move vertically upwards from the point $x = 4$ on the x-axis until you intersect the line representing the equation $y = 6x + 4$.

From the point of intersection on the line, move horizontally to the left towards the y-axis.

The value on the y-axis where the horizontal line intersects it is the total fare for travelling 4 km.

Using the equation (1) for verification, when $x=4$:

$y = 6(4) + 4$}

$y = 24 + 4$}

$y = 28$}

The point on the graph corresponding to a distance of 4 km is (4, 28).

Reading the y-coordinate when $x=4$ from the graph will give the value 28.

The fare for travelling a distance of 4 km is $\textsf{₹}28$.

Question 27. Prove that the angles opposite to equal sides of an isosceles triangle are equal. Using the above, find ∠B in a right triangle ABC, right angled at A with AB = AC.

Answer:

Solution:

Part 1: Proof of the theorem

Theorem: The angles opposite to equal sides of an isosceles triangle are equal.

Given:

In $\triangle$ABC, AB = AC.

To Prove:

$\angle$ABC = $\angle$ACB (or $\angle$B = $\angle$C).

Construction Required:

Draw AD, the angle bisector of $\angle$BAC, meeting BC at D.

Proof:

Consider $\triangle$ABD and $\triangle$ACD.

AB = AC

(Given)

$\angle$BAD = $\angle$CAD

(By construction, AD bisects $\angle$BAC)

AD = AD

(Common side)

Therefore, by the SAS (Side-Angle-Side) congruence rule:

$\triangle$ABD $\cong$ $\triangle$ACD

(By SAS congruence rule)

By CPCTC (Corresponding Parts of Congruent Triangles are Congruent), the corresponding angles are equal.

$\angle$ABD = $\angle$ACD

Thus, $\angle$B = $\angle$C.

Hence, the angles opposite to the equal sides AB and AC are equal.

Part 2: Finding $\angle$B in the given right triangle

Given:

$\triangle$ABC is a right triangle, right-angled at A ($\angle$A = $90^\circ$).

AB = AC.

To Find:

The value of $\angle$B.

Solution:

In $\triangle$ABC, we are given that AB = AC.

This means $\triangle$ABC is an isosceles triangle.

According to the theorem proved in Part 1, the angles opposite to the equal sides are equal.

The angle opposite to side AB is $\angle$C.

The angle opposite to side AC is $\angle$B.

Since AB = AC, we have:

$\angle$B = $\angle$C

(Angles opposite to equal sides)

In any triangle, the sum of the interior angles is $180^\circ$. For $\triangle$ABC, we have:

$\angle$A + $\angle$B + $\angle$C = $180^\circ$

... (i)

We are given that $\triangle$ABC is right-angled at A, so $\angle$A = $90^\circ$.

$\angle$A = $90^\circ$

(Given)

Substitute $\angle$A = $90^\circ$ and $\angle$C = $\angle$B into equation (i):

$90^\circ + \angle$B + $\angle$B = $180^\circ$

$90^\circ + 2\angle$B = $180^\circ$

Subtract $90^\circ$ from both sides:

$2\angle$B = $180^\circ - 90^\circ$

$2\angle$B = $90^\circ$

Divide by 2:

$\angle$B = $\frac{90^\circ}{2}$

$\angle$B = $45^\circ$

Therefore, $\angle$B is $45^\circ$. Since $\angle$B = $\angle$C, $\angle$C is also $45^\circ$.

The angles of the triangle are $90^\circ, 45^\circ, 45^\circ$, which sum up to $180^\circ$.

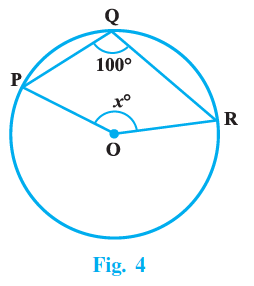

Question 28. Prove that the angle subtended by an arc at the centre is double the angle subtended by it at any point on the remaining part of the circle.

Using the above result, find x in figure 4 where O is the centre of the circle.

Answer:

Solution:

Part 1: Proof of the theorem

Theorem: The angle subtended by an arc at the centre is double the angle subtended by it at any point on the remaining part of the circle.

Given:

A circle with centre O.

Let PQ be an arc of the circle.

Let R be any point on the remaining part of the circle (the part not containing arc PQ).

To Prove:

$\angle$POQ = $2 \angle$PRQ, where $\angle$POQ is the angle subtended by arc PQ at the centre and $\angle$PRQ is the angle subtended by arc PQ at point R on the circumference.

Construction Required:

Join RO and extend it to meet the circle at a point M.

Proof:

Consider $\triangle$POR.

$OP = OR$ (Radii of the same circle)

Therefore, $\triangle$POR is an isosceles triangle.

The angles opposite to equal sides are equal:

$\angle$OPR = $\angle$ORP

... (i)

The exterior angle $\angle$POM of $\triangle$POR is equal to the sum of the two interior opposite angles:

$\angle$POM = $\angle$OPR + $\angle$ORP

Substituting $\angle$OPR = $\angle$ORP from (i):

$\angle$POM = $\angle$ORP + $\angle$ORP = $2\angle$ORP

... (ii)

Similarly, consider $\triangle$QOR.

$OQ = OR$ (Radii of the same circle)

Therefore, $\triangle$QOR is an isosceles triangle.

The angles opposite to equal sides are equal:

$\angle$OQR = $\angle$ORQ

... (iii)

The exterior angle $\angle$QOM of $\triangle$QOR is equal to the sum of the two interior opposite angles:

$\angle$QOM = $\angle$OQR + $\angle$ORQ

Substituting $\angle$OQR = $\angle$ORQ from (iii):

$\angle$QOM = $\angle$ORQ + $\angle$ORQ = $2\angle$ORQ

... (iv)

Now, consider the angle $\angle$POQ at the centre and $\angle$PRQ at the circumference.

There are different cases depending on the position of the arc and the point R:

Case 1: O lies inside $\angle$PRQ (This is the case shown in the standard diagram for the proof).

$\angle$POQ = $\angle$POM + $\angle$QOM

Substitute the results from (ii) and (iv):

$\angle$POQ = $2\angle$ORP + $2\angle$ORQ

Factor out 2:

$\angle$POQ = $2(\angle$ORP + $\angle$ORQ)

From the figure, $\angle$ORP + $\angle$ORQ = $\angle$PRQ.

$\angle$POQ = $2\angle$PRQ

Case 2: O lies outside $\angle$PRQ. The proof follows a similar logic using subtraction of angles (e.g., $\angle$POQ = $|\angle$QOM - $\angle$POM|$). The result $\angle$POQ = $2\angle$PRQ still holds.

Case 3: The arc PQ is a major arc. In this case, the angle subtended at the center is the reflex angle $\angle$POQ. The theorem states that Reflex $\angle$POQ = $2\angle$PRQ, where R is on the minor arc.

In all cases, the angle subtended by an arc at the center is double the angle subtended by it at any point on the remaining part of the circle.

Hence, proved.

Part 2: Finding x in Figure 4

Given:

A circle with centre O.

An angle at the circumference is $110^\circ$.

An angle at the center is labelled as $2x$.

To Find:

The value of $x$.

Solution:

In Figure 4, the angle at the circumference is $110^\circ$. Let the points on the circle defining the angles be P, Q, and R, such that the angle at the circumference is $\angle$PRQ = $110^\circ$. This angle is subtended by the major arc PQ.

The angle subtended by the same major arc PQ at the center O is the Reflex angle $\angle$POQ.

According to the theorem proved in Part 1 (Case 2 or 3 applied to the major arc):

Reflex $\angle$POQ = $2 \times \angle$PRQ

Reflex $\angle$POQ = $2 \times 110^\circ$

Reflex $\angle$POQ = $220^\circ$

The angle labelled $2x$ in the figure is the angle $\angle$POQ subtended by the minor arc PQ at the center O. The sum of the angle and the reflex angle at the center is $360^\circ$.

$\angle$POQ (minor) + Reflex $\angle$POQ = $360^\circ$

Substituting the value of the Reflex angle and the given expression for the minor angle:

$2x + 220^\circ = 360^\circ$

To solve for $x$, first subtract $220^\circ$ from both sides:

$2x = 360^\circ - 220^\circ$

$2x = 140^\circ$

Now, divide both sides by 2:

$x = \frac{140^\circ}{2}$

$x = 70^\circ$

The value of $x$ is $70^\circ$.

Question 29. A heap of wheat is in the form of a cone whose diameter is 48 m and height is 7 m. Find its volume. If the heap is to be covered by canvas to protect it from rain, find the area of the canvas required.

OR

A dome of a building is in the form of a hollow hemisphere. From inside, it was white-washed at the cost of Rs 498.96. If the rate of white washing is Rs 2.00 per square meter, find the volume of air inside the dome.

Answer:

Solution (for the first part):

Given:

The heap of wheat is in the form of a cone.

Diameter of the base of the cone, $d = 48$ m.

Height of the cone, $h = 7$ m.

To Find:

1. The volume of the cone.

2. The area of the canvas required to cover the heap (Lateral Surface Area of the cone).

Solution:

The radius of the base of the cone is half of the diameter.

Radius, $r = \frac{d}{2} = \frac{48}{2} = 24$ m.

1. Volume of the cone:

The formula for the volume of a cone is $V = \frac{1}{3}\pi r^2 h$.

Substitute the values $r=24$ m, $h=7$ m, and use $\pi = \frac{22}{7}$.

$V = \frac{1}{3} \times \frac{22}{7} \times (24)^2 \times 7$

$V = \frac{1}{3} \times \frac{22}{7} \times (24 \times 24) \times 7$

Cancel out the 7 in the numerator and denominator:

$V = \frac{1}{3} \times 22 \times 24 \times 24 \times \frac{\cancel{7}}{\cancel{7}}$

$V = \frac{1}{3} \times 22 \times 24 \times 24$

Cancel out the 3 with 24:

$V = 1 \times 22 \times \cancel{24}^8 \times 24$

$V = 22 \times 8 \times 24$

$V = 176 \times 24$

Calculate the product:

$\begin{array}{cc}& & 1 & 7 & 6 \\ \times & & & 2 & 4 \\ \hline && 7 & 0 & 4 \\ & 352 & \times \\ \hline 422 & 4 \\ \hline \end{array}$$V = 4224$

The volume of the cone is 4224 cubic meters.

Volume $= 4224 \text{ m}^3$

2. Area of canvas required:

The area of the canvas required to cover the heap is the lateral surface area of the cone. The formula for the lateral surface area of a cone is $LSA = \pi r l$, where $l$ is the slant height.

First, we need to calculate the slant height $l$ using the Pythagorean theorem: $l = \sqrt{r^2 + h^2}$.

Substitute the values $r=24$ m and $h=7$ m:

$l = \sqrt{(24)^2 + (7)^2}$

$l = \sqrt{576 + 49}$

$l = \sqrt{625}$

$l = 25$ m

Now, calculate the lateral surface area using $LSA = \pi r l$ with $r=24$ m, $l=25$ m, and $\pi = \frac{22}{7}$.

$LSA = \frac{22}{7} \times 24 \times 25$

$LSA = \frac{22}{7} \times 600$

$LSA = \frac{13200}{7}$

The area of the canvas required is $\frac{13200}{7}$ square meters.

Area of canvas $= \frac{13200}{7} \text{ m}^2$

(Approximately $1885.71$ m$^2$)

Final Answers:

Volume of the cone is 4224 m$^3$.

Area of the canvas required is $\frac{13200}{7}$ m$^2$.

Question 30. The following table gives the life times of 400 neon lamps

| Life time (in hours) | 300 - 400 | 400 - 500 | 500 - 600 | 600 - 700 | 700 - 800 | 800 - 900 | 900 - 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Lamps | 14 | 56 | 60 | 86 | 74 | 62 | 48 |

(i) Represent the given information with the help of a histogram.

(ii) How many lamps have a lifetime of less than 600 hours?

Answer:

Solution:

(i) Representation with the help of a histogram:

To represent the given frequency distribution using a histogram, we will follow these steps:

1. Draw horizontal and vertical axes. Label the horizontal axis as 'Life time (in hours)' and the vertical axis as 'Number of Lamps (Frequency)'.

2. The class intervals for the life time are 300-400, 400-500, 500-600, 600-700, 700-800, 800-900, and 900-1000. These are continuous and have uniform width (100 hours). Mark the points 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000 on the horizontal axis at equal distances.

3. Choose a suitable scale for the vertical axis to represent the frequencies (Number of Lamps). The frequencies range from 14 to 86. A scale where, for example, 1 unit on the vertical axis represents 10 lamps would be appropriate.

4. Construct rectangles with the class intervals as bases on the horizontal axis and heights corresponding to the frequencies of each class. For the interval 300-400, the height will be 14 units. For 400-500, the height will be 56 units, and so on.

5. The rectangles should be adjacent to each other without any gap, as the class intervals are continuous.

(ii) Number of lamps with a lifetime of less than 600 hours:

The lamps with a lifetime of less than 600 hours are those falling into the class intervals 300-400, 400-500, and 500-600.

From the table, the frequencies for these intervals are:

Life time 300-400 hours: 14 lamps

Life time 400-500 hours: 56 lamps

Life time 500-600 hours: 60 lamps

The total number of lamps with a lifetime of less than 600 hours is the sum of the frequencies of these three intervals.

Number of lamps $< 600$ hours = (Frequency of 300-400) + (Frequency of 400-500) + (Frequency of 500-600)

Number of lamps $< 600$ hours = $14 + 56 + 60$

Number of lamps $< 600$ hours = $70 + 60$

Number of lamps $< 600$ hours = $130$

There are 130 lamps that have a lifetime of less than 600 hours.