| Classwise Concept with Examples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

Chapter 3 Trigonometric Functions (Concepts)

Welcome to this significantly expanded exploration of Trigonometry, which dramatically broadens the scope beyond the confines of right-angled triangles studied in Class 10. While our previous work focused on trigonometric ratios defined by side lengths, this chapter generalizes these concepts, allowing us to analyze angles of any magnitude and explore the deeper, periodic nature of trigonometric relationships. This forms the essential basis for advanced applications in calculus, physics, engineering, and beyond.

We begin by redefining an angle not just as a static vertex between two lines, but as a dynamic measure of rotation of a ray around a fixed point (the vertex). This allows for angles greater than $90^\circ$ or even negative angles (representing rotation in the opposite direction). Alongside this, we introduce a crucial alternative unit for measuring angles: the radian. While degrees are familiar, radians provide a more natural mathematical measure, especially in calculus. We establish the fundamental conversion factor $\mathbf{\pi \text{ radians} = 180^\circ}$ and practice converting between these two systems ($\text{radians} = \text{degrees} \times \frac{\pi}{180}$ and $\text{degrees} = \text{radians} \times \frac{180}{\pi}$).

The core conceptual shift involves generalizing the trigonometric functions (sine, cosine, tangent, cosecant, secant, cotangent) beyond the SOH CAH TOA definitions. We utilize the unit circle approach. Consider a circle centered at the origin with radius 1 ($x^2 + y^2 = 1$). For any angle $\theta$ measured in standard position (initial side along the positive x-axis, rotation counter-clockwise), the terminal side of the angle intersects the unit circle at a unique point with coordinates $(x, y)$. We then define the primary trigonometric functions for any angle $\theta$ as:

- $\mathbf{\cos \theta = x}$

- $\mathbf{\sin \theta = y}$

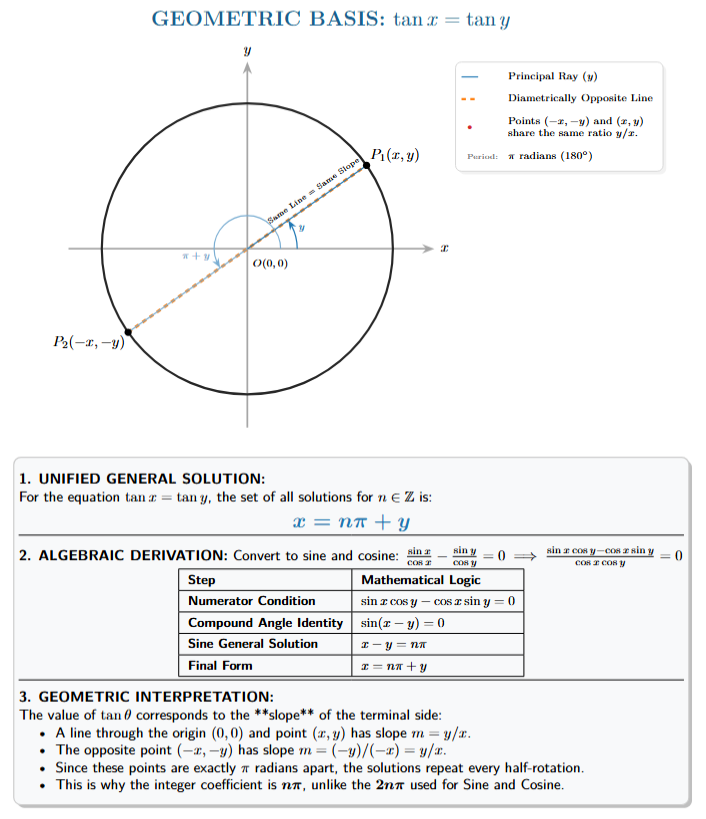

This generalized definition unveils the inherent periodic nature of trigonometric functions. Since adding a full rotation ($360^\circ$ or $2\pi$ radians) brings the terminal side back to the same position, the function values repeat. For example, $\sin(\theta + 2\pi) = \sin \theta$ and $\cos(\theta + 2\pi) = \cos \theta$ (period $2\pi$), while $\tan(\theta + \pi) = \tan \theta$ (period $\pi$). We study the characteristic graphs of these functions (like the sine wave), noting key features such as amplitude and period, which visually represent this repetition.

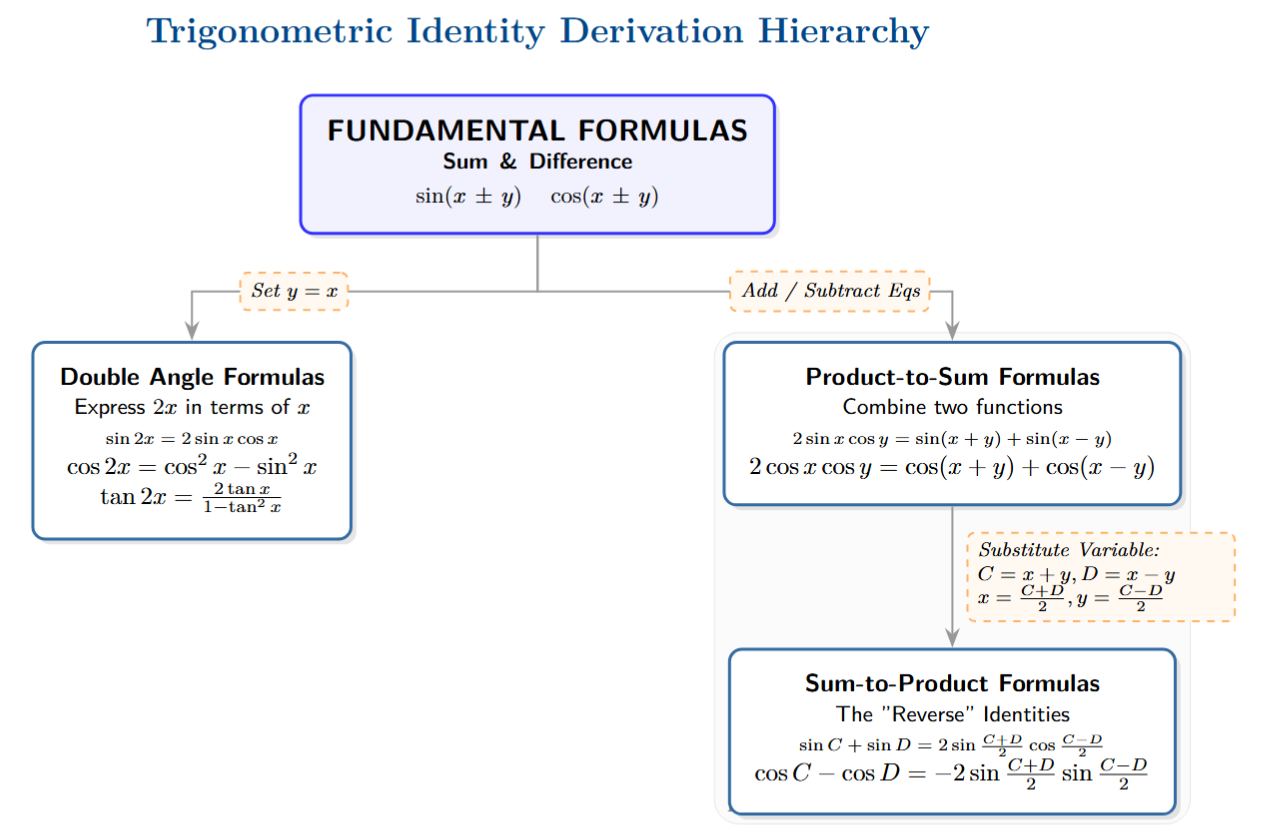

A major component of this chapter is the derivation and application of a vast array of Trigonometric Identities. Building upon the revisited reciprocal, quotient, and Pythagorean identities ($\sin^2\theta + \cos^2\theta = 1$, etc.), we develop formulas for:

- Sum and Difference Formulas: e.g., $\cos(A \pm B) = \cos A \cos B \mp \sin A \sin B$, $\sin(A \pm B) = \sin A \cos B \pm \cos A \sin B$, $\tan(A \pm B) = \frac{\tan A \pm \tan B}{1 \mp \tan A \tan B}$.

- Multiple Angle Formulas: Expressing functions of $2A$ or $3A$ in terms of functions of $A$ (e.g., $\sin 2A = 2\sin A \cos A$, $\cos 2A = \cos^2 A - \sin^2 A$).

- Submultiple Angle Formulas (related to half-angles).

- Product-to-Sum Formulas: Converting products like $\sin A \cos B$ into sums/differences.

- Sum-to-Product Formulas: Converting sums/differences like $\sin C + \sin D$ into products.

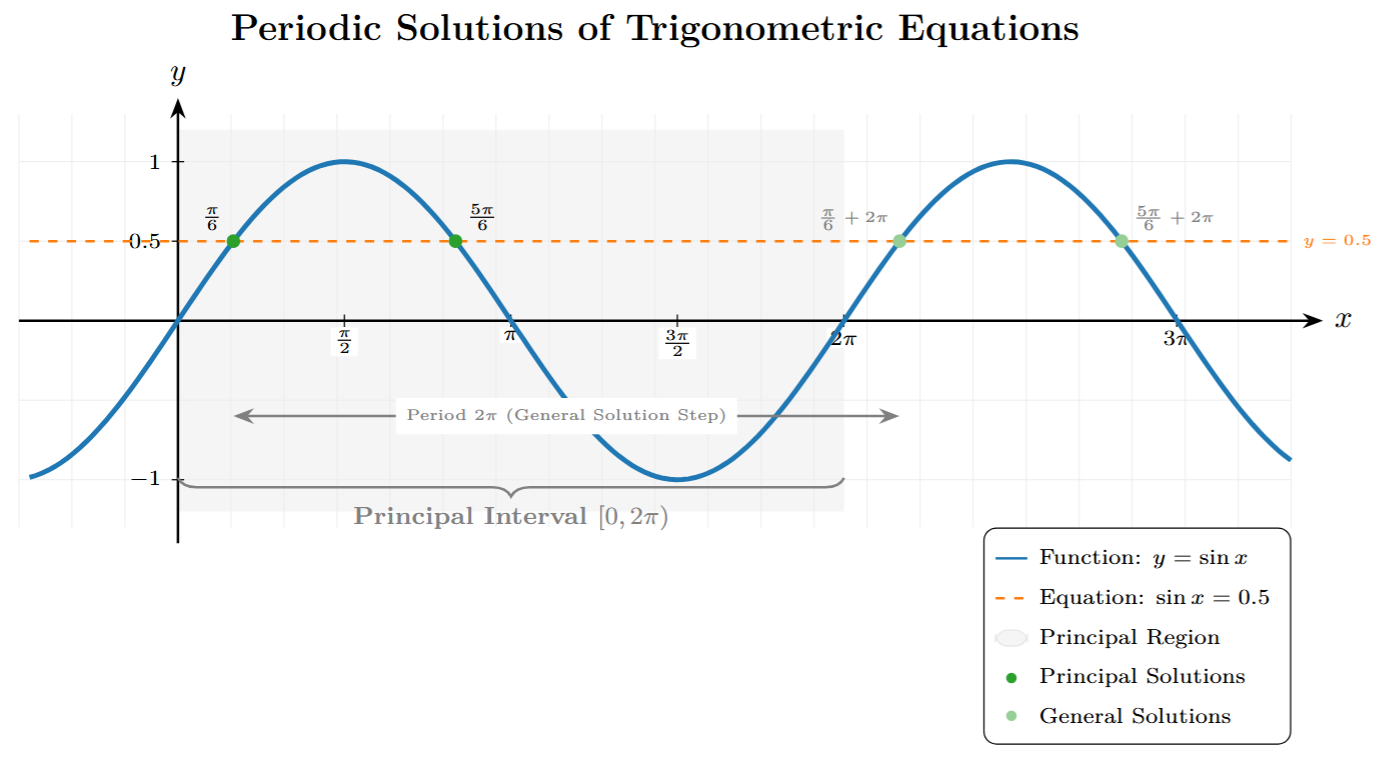

Finally, the chapter focuses on solving Trigonometric Equations – equations involving trigonometric functions of unknown angles. We learn methods to find:

- Principal Solutions: Solutions lying within a specific interval, typically $[0, 2\pi)$ or $0^\circ \le \theta < 360^\circ$.

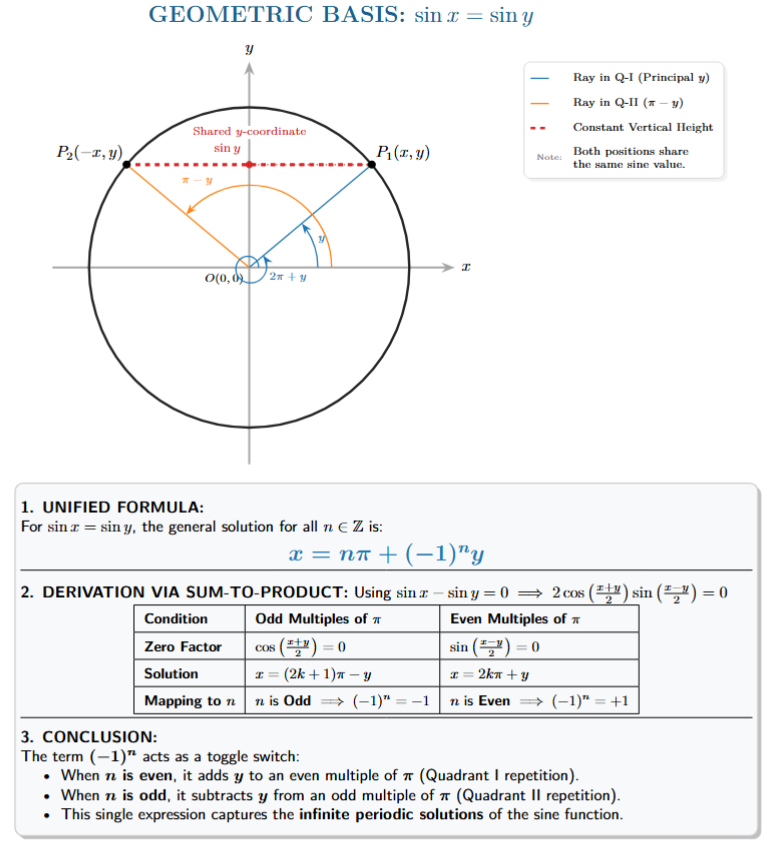

- General Solutions: Expressions that represent all possible solutions by incorporating the periodic nature of the functions, usually involving an integer $n$. For example, if $\sin x = \sin y$, the general solution is $x = n\pi + (-1)^n y$, where $n$ is any integer ($n \in \mathbb{Z}$).

Angle and Its Measurement

The foundation of trigonometry lies in the concept of an angle. In geometry, an angle is often seen as a static figure formed by two rays meeting at a common endpoint. However, in trigonometry, an angle is defined in a more dynamic sense: it is the measure of rotation of a ray about its initial point.

Imagine a ray, which we can call OA. If this ray rotates around its fixed starting point O, it sweeps out an angle. The key components of this angle are:

- Initial Side: The original position of the ray before the rotation begins (e.g., ray OA).

- Terminal Side: The final position of the ray after it has completed its rotation (e.g., ray OB).

- Vertex: The fixed point around which the rotation occurs (point O).

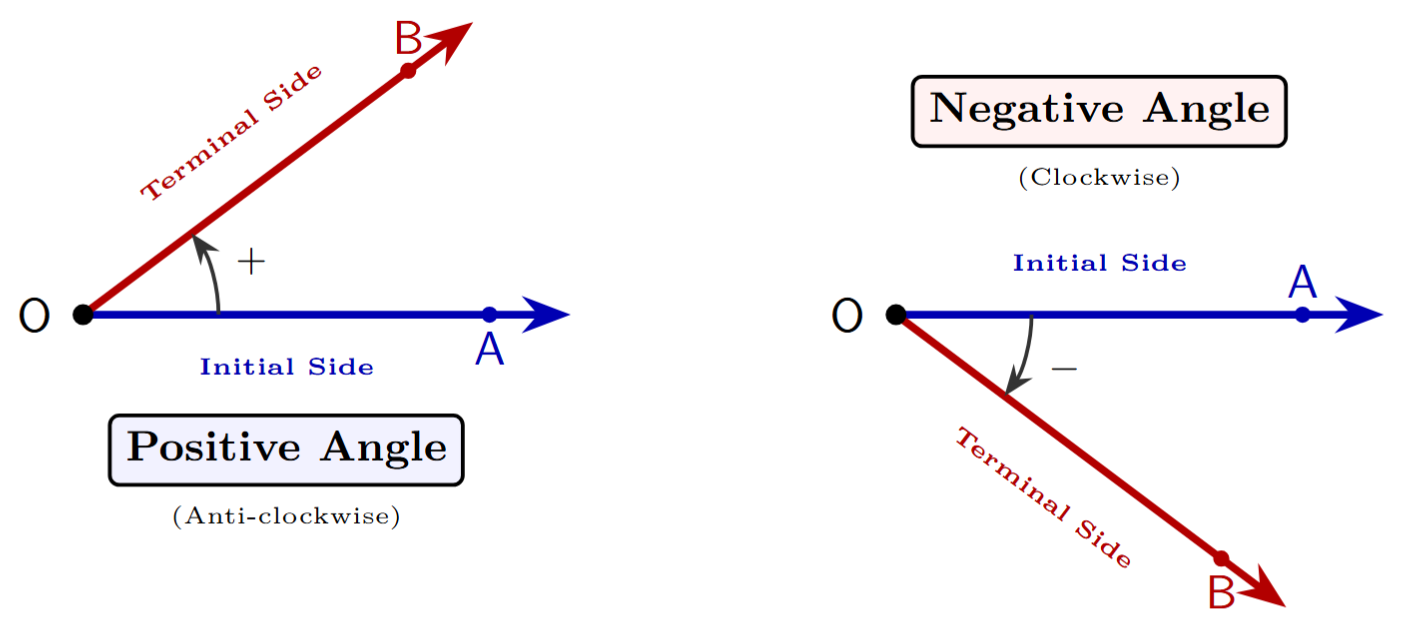

Positive and Negative Angles

The amount of rotation has a magnitude, but in trigonometry, its direction is equally important. This direction determines whether the angle is considered positive or negative, providing a crucial distinction for analyzing circular motion and periodic functions.

1. Positive Angle

An angle is considered positive if the direction of rotation from the initial side to the terminal side is anti-clockwise (or counter-clockwise). This is the direction opposite to the movement of the hands of a clock.

2. Negative Angle

An angle is considered negative if the direction of rotation from the initial side to the terminal side is clockwise. This is the same direction in which the hands of a clock move.

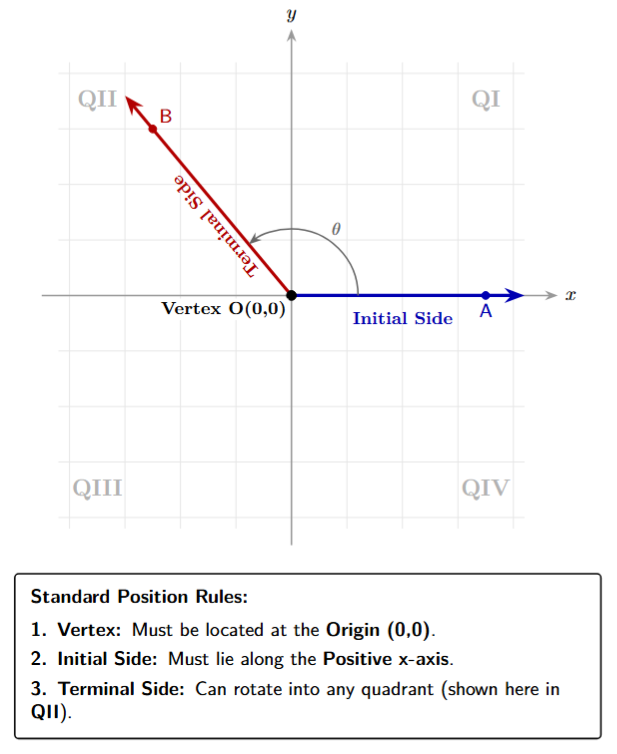

Angle in Standard Position

To have a consistent and universal way of representing angles, we place them in a standard position on the Cartesian coordinate plane (the x-y plane).

An angle is said to be in standard position if it satisfies two conditions:

- Its vertex is at the origin (0, 0) of the coordinate system.

- Its initial side lies along the positive x-axis.

When an angle is in standard position, the terminal side can lie in any of the four quadrants or on one of the axes. This standardized placement allows us to easily compare and analyze different angles.

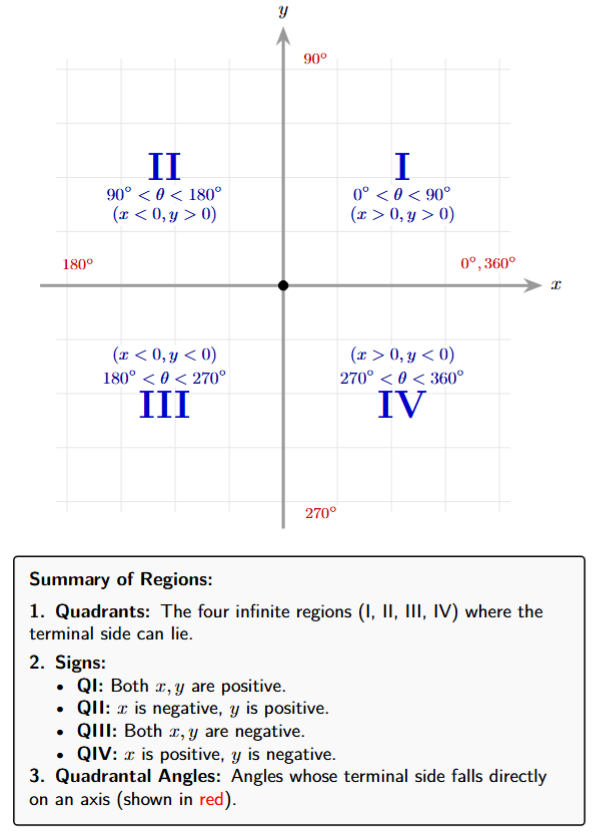

Quadrants and Quadrantal Angles

The x and y axes divide the Cartesian plane into four regions called quadrants. When an angle is in standard position, its terminal side determines which quadrant the angle lies in.

- Quadrant I: The terminal side lies in the first quadrant (where x > 0, y > 0). Angles are between 0° and 90°.

- Quadrant II: The terminal side lies in the second quadrant (where x < 0, y > 0). Angles are between 90° and 180°.

- Quadrant III: The terminal side lies in the third quadrant (where x < 0, y < 0). Angles are between 180° and 270°.

- Quadrant IV: The terminal side lies in the fourth quadrant (where x > 0, y < 0). Angles are between 270° and 360°.

If the terminal side of an angle in standard position lies on one of the axes (e.g., at 0°, 90°, 180°, 270°, 360°), it is called a quadrantal angle.

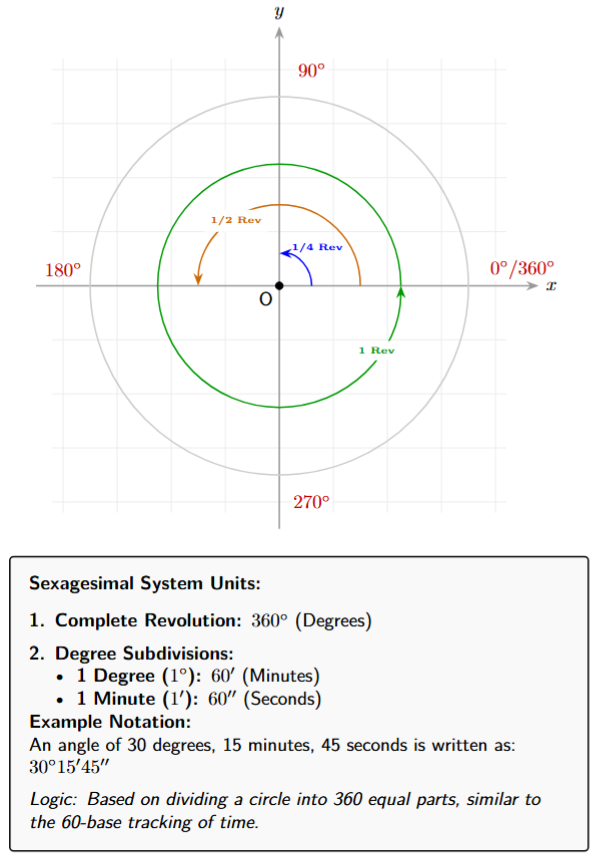

Systems of Measuring Angles:

There are two primary systems used for measuring angles: the Degree Measure and the Radian Measure.

1. Degree Measure (Sexagesimal System):

In the Degree system, a complete rotation of the ray is divided into 360 equal parts. Each part is called a degree. The symbol for degree is $^\circ$.

So, a complete revolution corresponds to $360^\circ$. A straight angle (half a revolution) is $180^\circ$, and a right angle (a quarter of a revolution) is $90^\circ$.

$1 \text{ revolution} = 360^\circ$

For finer measurements, a degree is subdivided into smaller units:

- One degree ($1^\circ$) is divided into 60 equal parts, called minutes. The symbol for a minute is $'$.

$1^\circ = 60'$ (Sixty minutes)

- One minute ($1'$) is divided into 60 equal parts, called seconds. The symbol for a second is $''$.

$1' = 60''$ (Sixty seconds)

For example, an angle of 30 degrees, 15 minutes, and 45 seconds is written as $30^\circ 15' 45''$.

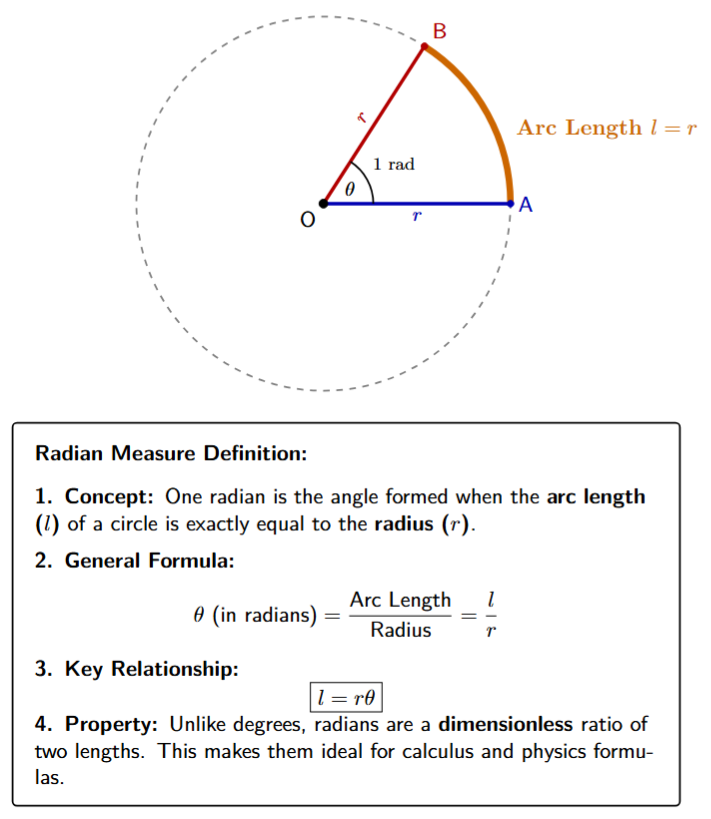

2. Radian Measure (Circular System):

The Radian system is the standard unit of angular measurement used in higher mathematics, particularly in calculus and physics. While the sexagesimal system (degrees) is based on arbitrary divisions, the radian measure is intrinsic to the geometry of the circle. It provides a direct link between the linear measure of an arc and the angular measure at the center.

Definition of Radian

One radian is defined as the measure of the angle subtended at the center of a circle by an arc whose length is exactly equal to the radius of that circle.

Consider a circle with center $O$ and radius $r$. Let an arc $AB$ be traced on the circumference such that the length of arc $AB$ ($l$) is equal to $r$. The angle $\angle AOB$ formed at the center is called 1 radian, denoted by $1^c$ or $1 \text{ rad}$.

Derivation of the Fundamental Formula

We know from geometry that the angles subtended by the arcs of a circle at the center are proportional to the lengths of the corresponding arcs.

The Relationship Between Arc, Radius, and Angle

Let a circle have radius $r$. Let an arc of length $l$ subtend an angle $\theta$ at the center. By the definition of a radian, an arc of length $r$ subtends an angle of $1 \text{ radian}$.

According to the property of circles:

$\frac{\text{Angle } \theta}{1 \text{ Radian}} = \frac{\text{Length of arc } l}{\text{Length of arc } r}$

... (i)

By simplifying the ratio:

$\theta = \frac{l}{r} \text{ radians}$

... (ii)

From equation (ii), we derive the primary formula for arc length:

$l = r\theta$

[Where $\theta$ is in radians]

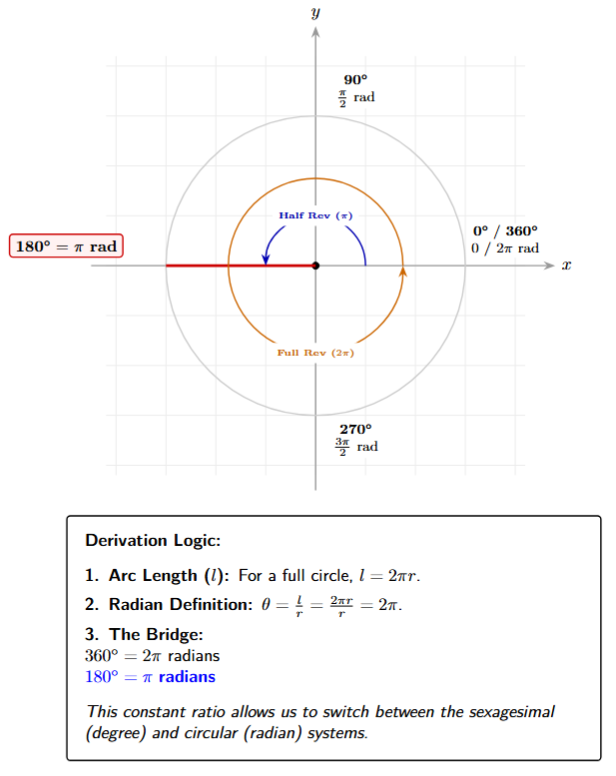

Relation Between Degree and Radian Measures

In trigonometry and geometry, angles can be measured in two primary units: degrees and radians. To work effectively with angles, it's crucial to understand the relationship between these two systems and how to convert from one to the other. The relationship is established by considering a complete revolution or a full circle.

Deriving the Fundamental Relationship

The core of the conversion lies in equating the measure of a full circle in both systems.

-

Full Revolution in Degrees: By definition, a complete revolution around a central point is divided into 360 degrees.

$1 \text{ complete revolution} = 360^\circ$

-

Full Revolution in Radians: The radian measure of an angle is defined by the formula $\theta = \frac{l}{r}$, where $l$ is the arc length and $r$ is the radius of the circle.

For a complete revolution, the arc length is the entire circumference of the circle, which is given by the formula $l = 2\pi r$.

Substituting this arc length into the radian formula, we get:

$\theta = \frac{2\pi r}{r} = 2\pi$

Thus, a complete revolution is equal to $2\pi$ radians.

-

Equating the Measures: Since both $360^\circ$ and $2\pi$ radians represent the same physical quantity (a full circle), we can set them equal to each other:

$360^\circ = 2\pi \text{ radians}$

Dividing both sides by 2 gives us the most common and fundamental relationship for conversion:

$180^\circ = \pi \text{ radians}$

Conversion Formulas

From the fundamental relationship $180^\circ = \pi \text{ radians}$, we can derive the specific conversion factors.

1. To Convert from Degrees to Radians:

To find the value of one degree, we can divide the fundamental relationship by 180:

$1^\circ = \frac{\pi}{180} \text{ radians}$

Therefore, to convert any angle from degrees to radians, you must multiply the degree measure by the conversion factor $\frac{\pi}{180}$.

Radian measure = Degree measure $\times \frac{\pi}{180}$

2. To Convert from Radians to Degrees:

To find the value of one radian, we can divide the fundamental relationship by $\pi$:

$1 \text{ radian} = \frac{180^\circ}{\pi}$

Using the approximation $\pi \approx 3.14159$, one radian is approximately $57.2958^\circ$, or more accurately $57^\circ 16'$.

Therefore, to convert any angle from radians to degrees, you must multiply the radian measure by the conversion factor $\frac{180}{\pi}$.

Degree measure = Radian measure $\times \frac{180}{\pi}$

Summary Table of Key Relations

| To Convert | Multiply by | Example: $60^\circ$ to Radians |

| Degrees to Radians | $\frac{\pi}{180}$ | $60 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \frac{\pi}{3}$ radians |

| Radians to Degrees | $\frac{180}{\pi}$ | $\frac{\pi}{3} \times \frac{180}{\pi} = 60^\circ$ |

Common Conversions:

Here are some common angle measures expressed in both degrees and radians:

| Degree | Radian |

|---|---|

| $0^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $30^\circ$ | $30 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \frac{\pi}{6}$ |

| $45^\circ$ | $45 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \frac{\pi}{4}$ |

| $60^\circ$ | $60 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \frac{\pi}{3}$ |

| $90^\circ$ | $90 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \frac{\pi}{2}$ |

| $180^\circ$ | $180 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \pi$ |

| $270^\circ$ | $270 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \frac{3\pi}{2}$ |

| $360^\circ$ | $360 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = 2\pi$ |

Example 1. Convert $45^\circ$ to radian measure.

Answer:

Given:

Angle in degree measure $= 45^\circ$.

To Find:

Equivalent angle in radian measure.

Solution:

We use the conversion formula from degrees to radians (Formula 5):

Radian measure = Degree measure $\times \frac{\pi}{180}$

Substitute the given degree measure:

Radian measure = $45 \times \frac{\pi}{180}$

Simplify the expression:

Radian measure = $\frac{45\pi}{180}$

We can simplify the fraction $\frac{45}{180}$ by dividing both numerator and denominator by their greatest common divisor, which is 45.

$\frac{\cancel{45}^{1} \times \pi}{\cancel{180}_{4}} = \frac{\pi}{4}$

So, $45^\circ$ is equal to $\frac{\pi}{4}$ radians.

The final answer is $\mathbf{\frac{\pi}{4} radians}$.

Example 2. Convert $\frac{2\pi}{3}$ radians to degree measure.

Answer:

Given:

Angle in radian measure $= \frac{2\pi}{3}$.

To Find:

Equivalent angle in degree measure.

Solution:

We use the conversion formula from radians to degrees (Formula 6):

Degree measure = Radian measure $\times \frac{180}{\pi}$

Substitute the given radian measure:

Degree measure = $\frac{2\pi}{3} \times \frac{180}{\pi}$

Simplify the expression by cancelling $\pi$ from numerator and denominator, and simplifying the numbers:

$\frac{2\cancel{\pi}}{\cancel{3}_{1}} \times \frac{\cancel{180}^{60}}{\cancel{\pi}} = 2 \times 60$

= $120$

So, $\frac{2\pi}{3}$ radians is equal to $120^\circ$.

The final answer is $\textbf{120}^\circ$.

Example 3. Convert $6^\circ$ into radians.

Answer:

Given:

Angle in degree measure $= 6^\circ$.

To Find:

Equivalent angle in radian measure.

Solution:

Using the conversion formula from degrees to radians (Formula 5):

Radian measure = Degree measure $\times \frac{\pi}{180}$

Substitute the given degree measure:

Radian measure = $6 \times \frac{\pi}{180}$

Simplify the fraction:

$\frac{\cancel{6}^{1} \times \pi}{\cancel{180}_{30}} = \frac{\pi}{30}$

So, $6^\circ$ is equal to $\frac{\pi}{30}$ radians.

The final answer is $\mathbf{\frac{\pi}{30} radians}$.

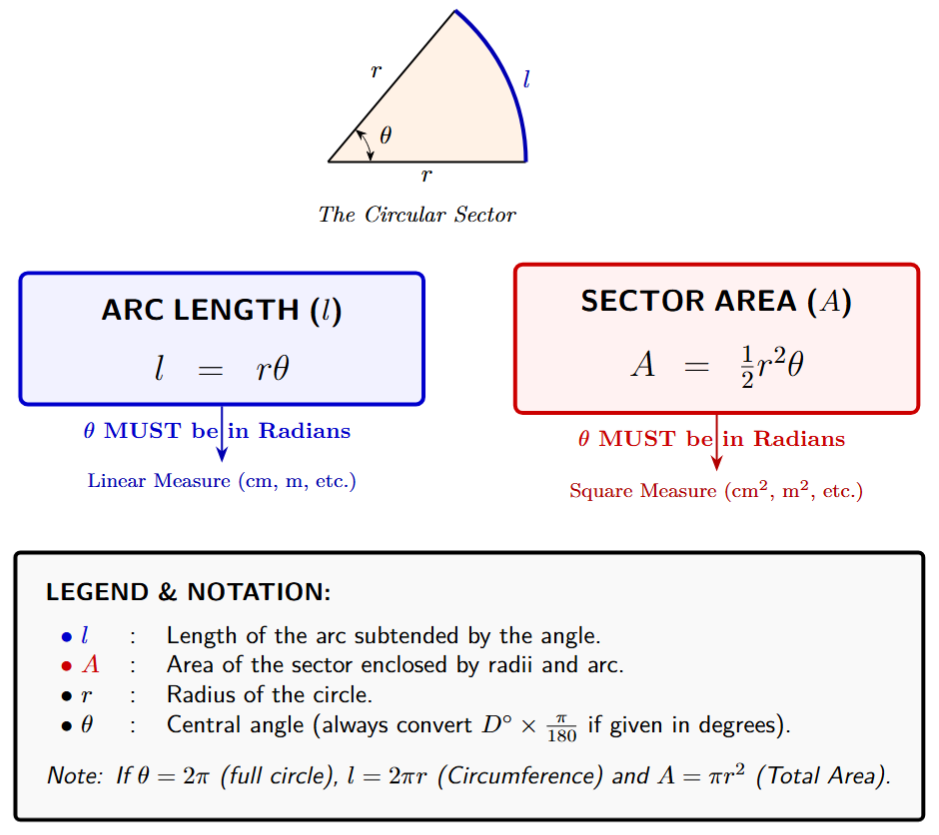

Length of an Arc and Area of a Sector

The radian measure of an angle provides a very natural and convenient relationship between the angle, the radius of a circle, and the length of the arc subtended by the angle at the center. This relationship is fundamental for solving problems involving sectors and arcs of circles.

Length of an Arc

Consider a circle with radius $r$. An arc of this circle subtends a central angle $\theta$ at the center. The length of this arc, denoted by $l$, is directly proportional to both the radius $r$ and the central angle $\theta$.

The formula relating arc length ($l$), radius ($r$), and the central angle ($\theta$) is:

$l = r\theta$

This formula is valid only when the angle $\theta$ is measured in radians. If the angle is given in degrees, it must first be converted to radians by multiplying by the conversion factor $\frac{\pi}{180}$.

Derivation of the Arc Length Formula ($l = r\theta$)

The derivation is based on the principle of proportionality. In any circle, the ratio of the length of an arc to the total circumference is equal to the ratio of the angle subtended by that arc to the angle of a full circle ($360^\circ$ or $2\pi$ radians).

We can set up a proportion using radian measures:

$\frac{\text{Length of Arc}}{\text{Circumference}} = \frac{\text{Central Angle of Arc}}{\text{Angle of Full Circle}}$

Substituting the corresponding values:

$\frac{l}{2\pi r} = \frac{\theta}{2\pi}$

To solve for $l$, we multiply both sides by $2\pi r$:

$l = \left(\frac{\theta}{2\pi}\right) \times 2\pi r$

By canceling the $2\pi$ terms, we arrive at the formula:

$l = \theta \times r \implies \boldsymbol{l = r\theta}$

Area of a Sector

A sector of a circle is the pie-shaped region enclosed by two radii and the arc between them. Similar to arc length, the area of a sector is directly proportional to its central angle $\theta$.

For a circle of radius $r$, the area ($A$) of a sector with a central angle $\theta$ is given by the formula:

$A = \frac{1}{2}r^2\theta$

As with the arc length formula, the angle $\theta$ in this formula must be in radians.

Derivation of the Area of a Sector Formula ($A = \frac{1}{2}r^2\theta$)

The derivation uses the same proportionality principle. The ratio of the area of a sector to the area of the entire circle is equal to the ratio of the sector's central angle to the angle of a full circle.

$\frac{\text{Area of Sector}}{\text{Area of Full Circle}} = \frac{\text{Central Angle of Sector}}{\text{Angle of Full Circle}}$

The area of a full circle is $\pi r^2$. Substituting the values into the proportion:

$\frac{A}{\pi r^2} = \frac{\theta}{2\pi}$

To solve for $A$, we multiply both sides by $\pi r^2$:

$A = \left(\frac{\theta}{2\pi}\right) \times \pi r^2$

We can cancel the $\pi$ term from the numerator and denominator:

$A = \frac{\theta}{2\cancel{\pi}} \times \cancel{\pi} r^2 = \frac{\theta r^2}{2}$

Rearranging this gives the standard form of the formula:

$\boldsymbol{A = \frac{1}{2}r^2\theta}$

Example 1. A circle has a radius of 5 cm. Find the length of the arc subtended by a central angle of $60^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

Radius of the circle, $r = 5$ cm.

Central angle $= 60^\circ$.

To Find:

Length of the arc ($l$).

Solution:

The formula for arc length $l = r\theta$ requires the angle $\theta$ to be in radians. The given angle is in degrees, so we first convert $60^\circ$ to radians using the conversion formula:

Radian measure = Degree measure $\times \frac{\pi}{180}$

$\theta = 60^\circ \times \frac{\pi}{180}$ radians

Simplify the expression:

$\theta = \frac{60\pi}{180}$ radians

$\theta = \frac{\cancel{60}^{1} \times \pi}{\cancel{180}_{3}}$ radians

$\theta = \frac{\pi}{3}$ radians

Now that the angle is in radians, we can use the arc length formula $l = r\theta$ (Formula 1):

$l = r\theta$

Substitute the values of $r$ and $\theta$:

$l = 5 \times \frac{\pi}{3}$

$l = \frac{5\pi}{3}$

The length of the arc is $\frac{5\pi}{3}$ cm.

The final answer is $\mathbf{\frac{5\pi}{3} cm}$.

Example 2. A sector of a circle with radius 8 cm has a central angle of $\frac{3\pi}{4}$ radians. Find the area of the sector.

Answer:

Given:

Radius of the circle, $r = 8$ cm.

Central angle, $\theta = \frac{3\pi}{4}$ radians.

To Find:

Area of the sector ($A$).

Solution:

The central angle is given in radians ($\frac{3\pi}{4}$ radians), so we can directly use the formula for the area of a sector $A = \frac{1}{2}r^2\theta$ (Formula 2):

$A = \frac{1}{2}r^2\theta$

Substitute the given values of $r$ and $\theta$:

$A = \frac{1}{2} \times (8)^2 \times \frac{3\pi}{4}$

Calculate $(8)^2$:

$A = \frac{1}{2} \times 64 \times \frac{3\pi}{4}$

Simplify the expression. We can multiply $\frac{1}{2}$ and 64, and then simplify with the denominator 4:

$A = 32 \times \frac{3\pi}{4}$

$A = \cancel{32}^{8} \times \frac{3\pi}{\cancel{4}_{1}}$

$A = 8 \times 3\pi$

$A = 24\pi$

The area of the sector is $24\pi$ square centimeters.

The final answer is $\mathbf{24\pi cm}^\mathbf{2}$.

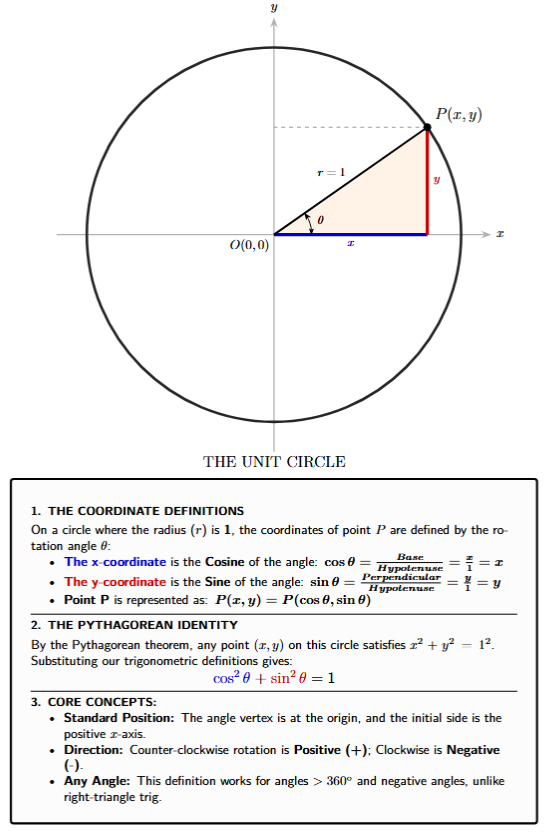

Trigonometric Functions of a Real Number

In earlier classes, you learned about trigonometric ratios of acute angles in right-angled triangles (angles between $0^\circ$ and $90^\circ$). These ratios ($\sin \theta, \cos \theta, \tan \theta$, etc.) relate the angles of a right triangle to the lengths of its sides. However, to analyze periodic phenomena and use trigonometry in calculus and other advanced topics, we need to extend the definitions of these ratios to angles of any magnitude (positive or negative) and define them as functions of a real number.

This extension is done using the concept of the unit circle and defining trigonometric functions based on the coordinates of a point on this circle.

The Unit Circle: A Broader Definition of Trigonometric Functions

While mnemonics like Pandit Badri Prasad or SOH-CAH-TOA work perfectly for defining trigonometric ratios for acute angles within a right-angled triangle, this approach is inherently limited. The unit circle provides a more powerful and comprehensive way to define trigonometric functions for any angle, regardless of its size or sign.

What is the Unit Circle?

The unit circle is a circle drawn on the Cartesian coordinate plane with two specific properties:

- Its center is located at the origin, point $(0, 0)$.

- Its radius ($r$) is exactly 1 unit.

Because its radius is 1, any point $(x, y)$ on the circumference of the unit circle must satisfy its equation: $x^2 + y^2 = 1^2$, or simply $\boldsymbol{x^2 + y^2 = 1}$.

Defining Sine and Cosine using the Unit Circle

Imagine an angle $\theta$ placed in a "standard position" on the Cartesian plane. This means its vertex is at the origin $(0, 0)$ and its starting side (initial side) lies along the positive x-axis. The other side (terminal side) rotates counter-clockwise by an amount $\theta$.

This rotating terminal side will eventually intersect the circumference of the unit circle at a unique point, which we can label $P(x, y)$.

Connecting to Right-Triangle Trigonometry

To understand why the coordinates of this point are so special, let's create a right-angled triangle by dropping a perpendicular line from the point $P(x, y)$ down to the x-axis. This gives us a triangle with:

- A horizontal side (Base or Adjacent side) of length $x$.

- A vertical side (Perpendicular or Opposite side) of length $y$.

- The hypotenuse, which is the radius of the unit circle, has a length of 1.

Now, let's apply our standard trigonometric definitions ("Pandit Badri Prasad" or SOH-CAH-TOA) to this triangle:

- $\sin \theta = \frac{\text{Perpendicular}}{\text{Hypotenuse}} = \frac{y}{1} = y$

- $\cos \theta = \frac{\text{Base}}{\text{Hypotenuse}} = \frac{x}{1} = x$

This reveals the crucial connection: the x and y coordinates of the point on the unit circle are precisely the cosine and sine of the angle $\theta$. The definition works so cleanly because the hypotenuse is 1, simplifying the ratios.

The Formal Definition and Its Implication

Because of this relationship, we can formally define sine and cosine for any angle $\theta$ based on the coordinates of the intersection point $P(x, y)$ on the unit circle:

- The x-coordinate of the point is defined as the cosine of the angle: $\boldsymbol{x = \cos \theta}$

- The y-coordinate of the point is defined as the sine of the angle: $\boldsymbol{y = \sin \theta}$

This is a powerful concept. It means that any point on the unit circle can be represented not just by its Cartesian coordinates $(x, y)$, but also by its trigonometric coordinates $(\cos \theta, \sin \theta)$, where $\theta$ is the angle that leads to that point.

The Fundamental Pythagorean Identity

This unit circle definition leads directly to the most fundamental identity in trigonometry. We know that every point $(x, y)$ on the unit circle must satisfy its equation:

$x^2 + y^2 = 1$

By substituting our new definitions for $x$ and $y$ into this equation, we get:

$(\cos \theta)^2 + (\sin \theta)^2 = 1$

This is universally written as the Pythagorean Identity:

$\boldsymbol{\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta = 1}$

This identity holds true for any real number $\theta$, making it a cornerstone of trigonometry.

Trigonometric Ratios in All Four Quadrants using the Unit Circle

The unit circle provides a powerful framework for understanding the values and, critically, the signs (positive or negative) of trigonometric functions for any angle. The sign of each function is determined by the quadrant in which the angle's terminal side lies.

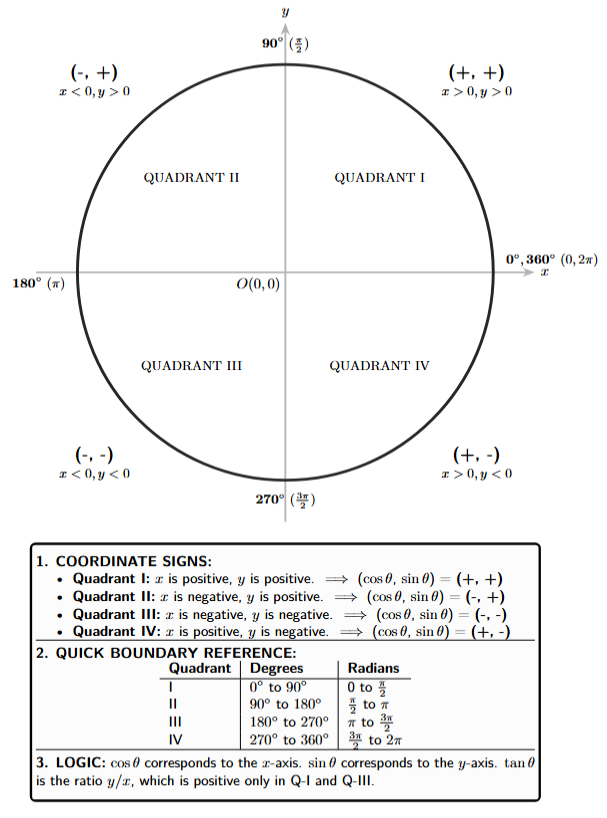

The Four Quadrants and Coordinate Signs

The Cartesian plane is divided into four quadrants by the x and y axes. An angle $\theta$ is in a specific quadrant if its terminal side lies in that quadrant.

The key is to remember the sign of the x and y coordinates in each quadrant. Since on the unit circle, $\boldsymbol{\cos \theta = x}$ and $\boldsymbol{\sin \theta = y}$, the signs of sine and cosine directly follow the signs of the coordinates.

- Quadrant I ($0^\circ < \theta < 90^\circ$ or $0 < \theta < \frac{\pi}{2}$): Both x and y are positive. $(x, y) = (+, +)$.

- Quadrant II ($90^\circ < \theta < 180^\circ$ or $\frac{\pi}{2} < \theta < \pi$): x is negative, y is positive. $(x, y) = (-, +)$.

- Quadrant III ($180^\circ < \theta < 270^\circ$ or $\pi < \theta < \frac{3\pi}{2}$): Both x and y are negative. $(x, y) = (-, -)$.

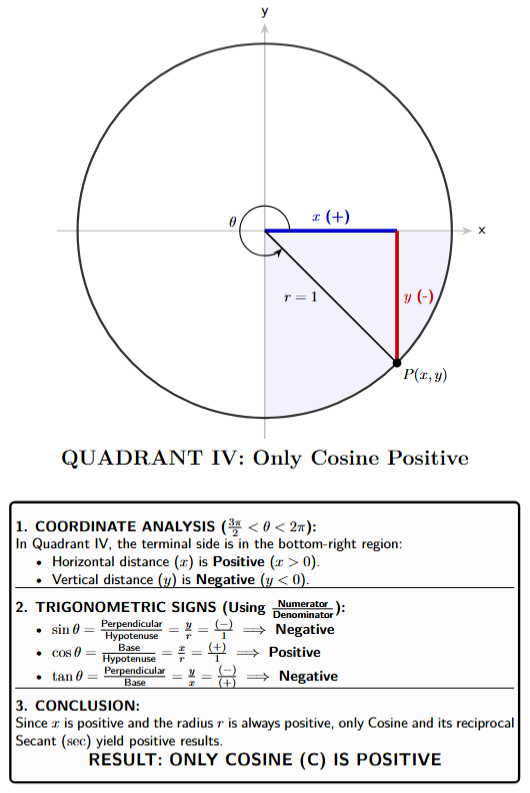

- Quadrant IV ($270^\circ < \theta < 360^\circ$ or $\frac{3\pi}{2} < \theta < 2\pi$): x is positive, y is negative. $(x, y) = (+, -)$.

Signs of Trigonometric Ratios by Quadrant

We can now determine the sign of all six trigonometric ratios in each quadrant. Remember that $\tan \theta = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}$, and the reciprocal functions ($\text{cosec}, \sec, \cot$) will have the same sign as their parent functions ($\sin, \cos, \tan$).

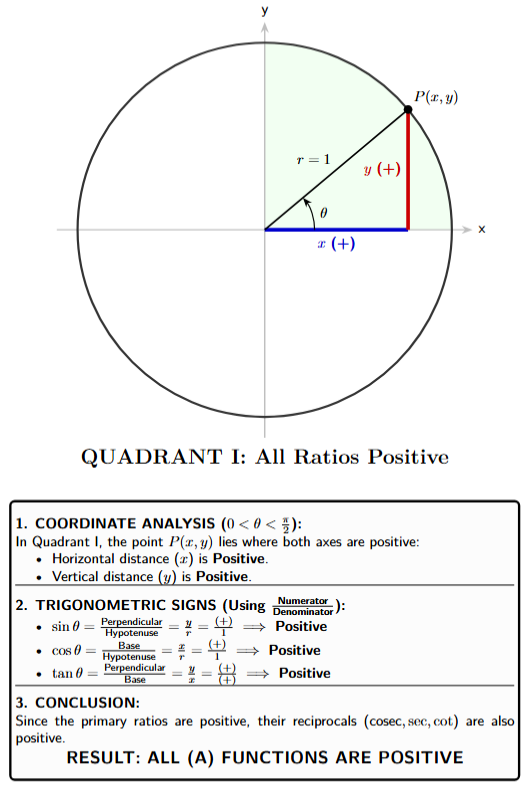

Quadrant I $(+, +)$

- $\sin \theta = y$ is Positive

- $\cos \theta = x$ is Positive

- $\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x} = \frac{+}{+}$ is Positive

- Conclusion: All trigonometric ratios are positive.

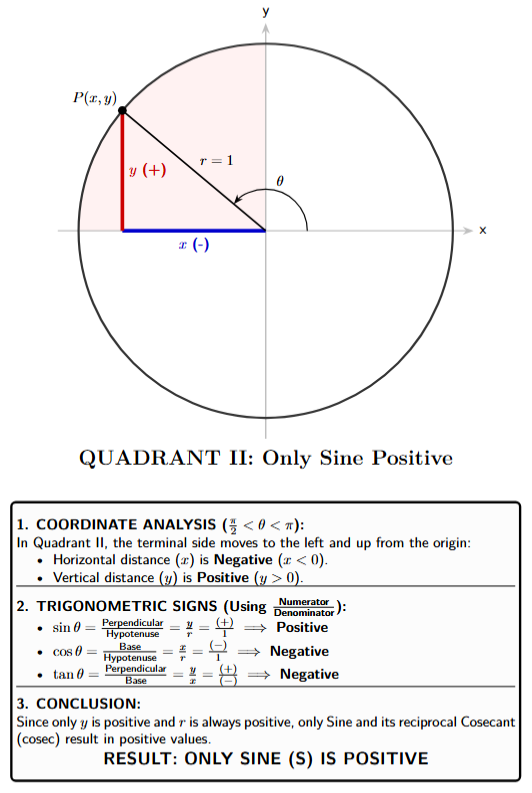

Quadrant II $(-, +)$

- $\sin \theta = y$ is Positive

- $\cos \theta = x$ is Negative

- $\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x} = \frac{+}{-}$ is Negative

- Conclusion: Only Sine and its reciprocal, Cosecant, are positive.

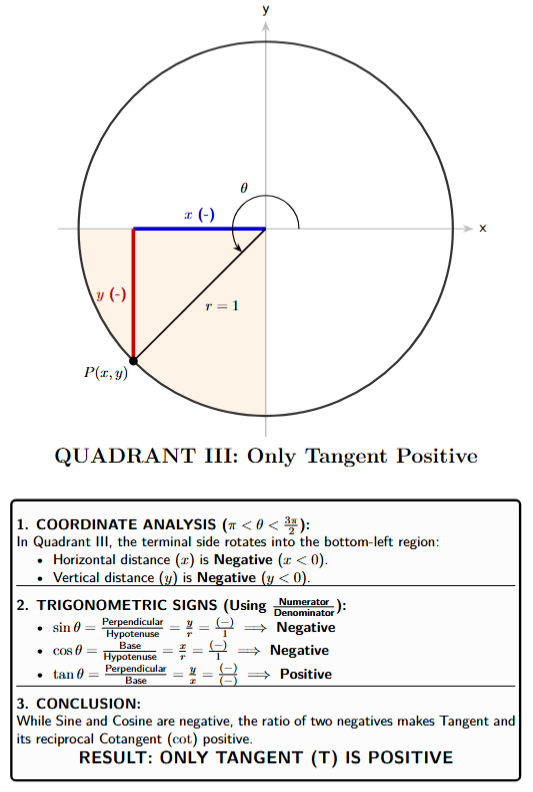

Quadrant III $(-, -)$

- $\sin \theta = y$ is Negative

- $\cos \theta = x$ is Negative

- $\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x} = \frac{-}{-}$ is Positive

- Conclusion: Only Tangent and its reciprocal, Cotangent, are positive.

Quadrant IV $(+, -)$

- $\sin \theta = y$ is Negative

- $\cos \theta = x$ is Positive

- $\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x} = \frac{-}{+}$ is Negative

- Conclusion: Only Cosine and its reciprocal, Secant, are positive.

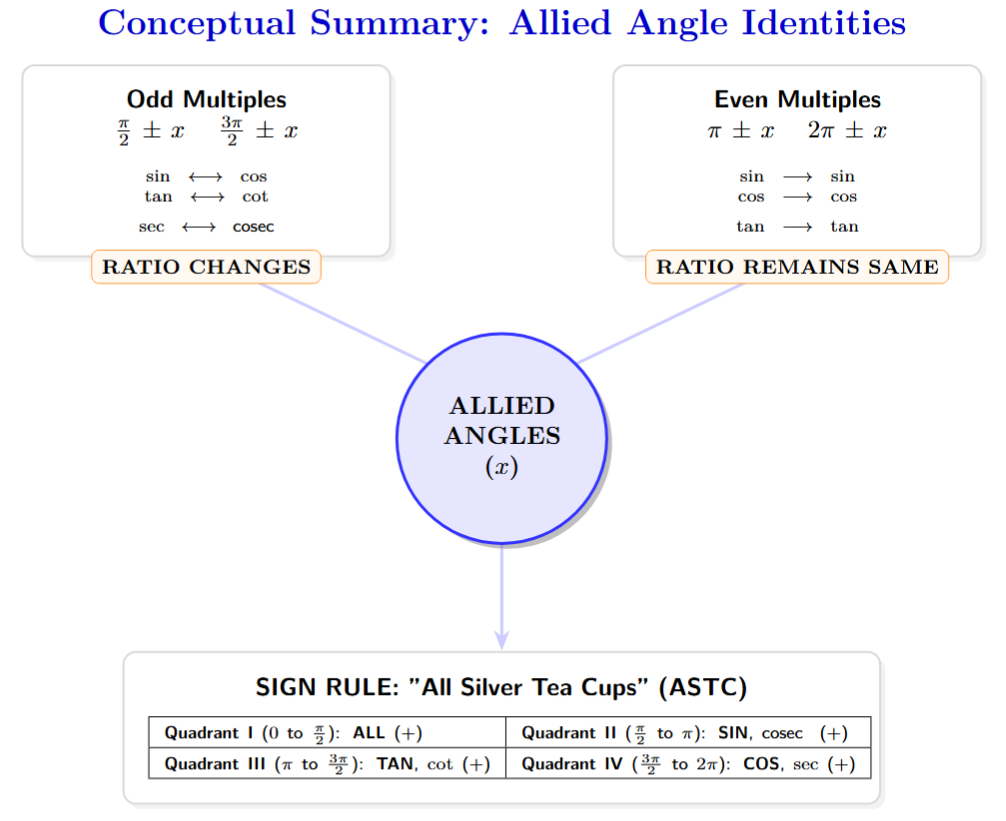

The ASTC Rule: A Mnemonic for Remembering the Signs

A simple way to remember which functions are positive in each quadrant is the ASTC rule, often remembered with the phrase "All Students Take Calculus" or "Add Sugar To Coffee". Starting from Quadrant I and moving counter-clockwise:

- A (Quadrant I): All ratios are positive.

- S (Quadrant II): Sine (and $\text{cosec}$) is positive.

- T (Quadrant III): Tangent (and $\cot$) is positive.

- C (Quadrant IV): Cosine (and $\sec$) is positive.

Summary Table

| Quadrant | Angle Range (Degrees) | Angle Range (Radians) | Signs of (x, y) | Positive Ratios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | $0^\circ - 90^\circ$ | $0 - \frac{\pi}{2}$ | $(+, +)$ | All ($\sin, \cos, \tan, \text{cosec}, \sec, \cot$) |

| II | $90^\circ - 180^\circ$ | $\frac{\pi}{2} - \pi$ | $(-, +)$ | Sine, Cosecant |

| III | $180^\circ - 270^\circ$ | $\pi - \frac{3\pi}{2}$ | $(-, -)$ | Tangent, Cotangent |

| IV | $270^\circ - 360^\circ$ | $\frac{3\pi}{2} - 2\pi$ | $(+, -)$ | Cosine, Secant |

Why This Definition is Powerful

The transition from right-angled triangle trigonometry to the unit circle definition is a significant leap in mathematical analysis. While the triangle-based approach is intuitive, it restricts the angle $\theta$ to be acute ($0^\circ < \theta < 90^\circ$). The unit circle definition is universally applicable and offers several advantages:

1. Extension of Angles: It allows us to calculate trigonometric values for obtuse angles ($90^\circ$ to $180^\circ$), reflex angles, and even angles greater than $360^\circ$ (representing multiple full rotations).

2. Negative Angles: It provides a clear geometric interpretation for negative angles, which represent clockwise rotation from the positive x-axis.

3. Periodicity: It naturally illustrates that trigonometric functions are periodic. Since the point $P(x, y)$ returns to the same position after every $2\pi$ radians (or $360^\circ$), the values of sine and cosine repeat.

4. Coordinate Geometry Integration: It links trigonometry directly with the Cartesian coordinate system, making it indispensable for Calculus, Physics, and Engineering.

Definition of Trigonometric Functions:

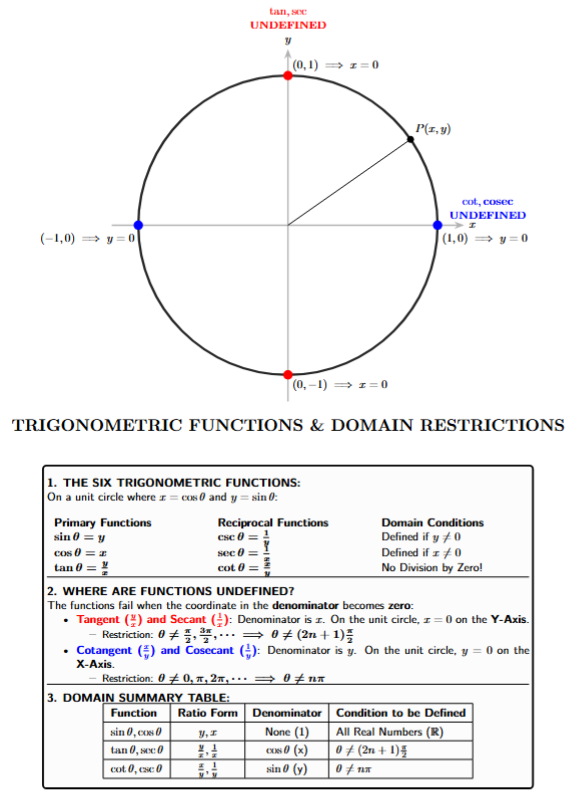

Let a real number $\theta$ represent an angle (in radians) in the standard position. Let $P(x, y)$ be the point where the terminal side of $\theta$ intersects the unit circle $x^2 + y^2 = 1$. The six trigonometric functions are defined as follows:

Primary Functions

1. The Sine Function

The sine of $\theta$ is defined as the y-coordinate of the point $P$.

$\sin \theta = y$

2. The Cosine Function

The cosine of $\theta$ is defined as the x-coordinate of the point $P$.

$\cos \theta = x$

3. The Tangent Function

The tangent of $\theta$ is the ratio of the y-coordinate to the x-coordinate.

$\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x} = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}$

[Provided $\cos \theta \neq 0$]

Reciprocal Functions

4. The Cosecant Function

The cosecant of $\theta$ is the reciprocal of the y-coordinate (or sine).

$\text{cosec} \theta = \frac{1}{y} = \frac{1}{\sin \theta}$

[Provided $\sin \theta \neq 0$]

5. The Secant Function

The secant of $\theta$ is the reciprocal of the x-coordinate (or cosine).

$\sec \theta = \frac{1}{x} = \frac{1}{\cos \theta}$

[Provided $\cos \theta \neq 0$]

6. The Cotangent Function

The cotangent of $\theta$ is the ratio of the x-coordinate to the y-coordinate.

$\cot \theta = \frac{x}{y} = \frac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta} = \frac{1}{\tan \theta}$

[Provided $\sin \theta \neq 0$]

The Problem of Division by Zero

In mathematics, division by zero is undefined. When we define trigonometric functions using ratios (like $\frac{y}{x}$ or $\frac{1}{y}$), we must ensure that the denominator never becomes zero. If the denominator were allowed to be zero, the function would fail to provide a real number output, leading to what is known as a discontinuity or an asymptote.

Since these functions are defined based on the unit circle coordinates $(x, y)$, where $x = \cos \theta$ and $y = \sin \theta$, the restrictions depend entirely on where the point $P$ lies on the axes.

Restrictions for Tan and Sec ($\cos \theta \neq 0$)

The functions Tangent ($\frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}$) and Secant ($\frac{1}{\cos \theta}$) both have $\cos \theta$ (the x-coordinate) in the denominator.

When does $\cos \theta = 0$?

On the unit circle, the x-coordinate is zero when the point $P$ lies exactly on the Y-axis. This happens at:

- $\theta = 90^\circ$ (or $\frac{\pi}{2}$ radians)

- $\theta = 270^\circ$ (or $\frac{3\pi}{2}$ radians)

General Formula for Restriction

To prevent division by zero, $\theta$ cannot be any odd multiple of $90^\circ$. In radian measure, we express this as:

$\theta \neq (2n + 1)\frac{\pi}{2}$

[where $n$ is any integer]

If we substitute any such value into $\tan \theta$, the ratio becomes $\frac{y}{0}$, which is undefined.

Restrictions for Cot and Cosec ($\sin \theta \neq 0$)

The functions Cotangent ($\frac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}$) and Cosecant ($\frac{1}{\sin \theta}$) both have $\sin \theta$ (the y-coordinate) in the denominator.

When does $\sin \theta = 0$?

On the unit circle, the y-coordinate is zero when the point $P$ lies exactly on the X-axis. This happens at:

- $\theta = 0^\circ, 180^\circ, 360^\circ, \dots$

- In radians: $0, \pi, 2\pi, \dots$

General Formula for Restriction

To prevent division by zero, $\theta$ cannot be any multiple of $180^\circ$. In radian measure, we express this as:

$\theta \neq n\pi$

[where $n$ is any integer]

If we attempt to calculate $\text{cosec}(180^\circ)$, the ratio becomes $\frac{1}{0}$, which is undefined.

Summary of Domain Restrictions

The "Domain" of a function is the set of all possible input values ($\theta$) for which the function is defined. To prevent mathematical errors, we exclude the "zero-denominator" points from the domain.

| Function | Ratio Form | Denominator | Condition to be Defined |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\sin \theta, \cos \theta$ | $y, x$ | None (1) | All Real Numbers ($\mathbb{R}$) |

| $\tan \theta, \sec \theta$ | $\frac{y}{x}, \frac{1}{x}$ | $\cos \theta$ | $\theta \neq (2n+1)\frac{\pi}{2}$ |

| $\cot \theta, \text{cosec} \theta$ | $\frac{x}{y}, \frac{1}{y}$ | $\sin \theta$ | $\theta \neq n\pi$ |

Pythagorean Identities Derived from $\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta = 1$:

From the fundamental identity $\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta = 1$, we can derive two more important identities:

1. Divide $\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta = 1$ by $\cos^2 \theta$, assuming $\cos \theta \neq 0$:

$\frac{\cos^2 \theta}{\cos^2 \theta} + \frac{\sin^2 \theta}{\cos^2 \theta} = \frac{1}{\cos^2 \theta}$

$1 + \left(\frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}\right)^2$

Using the definitions $\tan \theta = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}$ and $\sec \theta = \frac{1}{\cos \theta}$, we get:

$$1 + \tan^2 \theta = \sec^2 \theta$$

This identity is valid for all real numbers $\theta$ where $\cos \theta \neq 0$, i.e., $\theta \neq (2n+1)\frac{\pi}{2}$ for integer $n$.

2. Divide $\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta = 1$ by $\sin^2 \theta$, assuming $\sin \theta \neq 0$:

$\frac{\cos^2 \theta}{\sin^2 \theta} + \frac{\sin^2 \theta}{\sin^2 \theta} = \frac{1}{\sin^2 \theta}$

$\left(\frac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}\right)^2 + 1 = \left(\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^2$

Using the definitions $\cot \theta = \frac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}$ and $\text{cosec} \theta = \frac{1}{\sin \theta}$, we get:

$$\cot^2 \theta + 1 = \text{cosec}^2 \theta$$

This identity is valid for all real numbers $\theta$ where $\sin \theta \neq 0$, i.e., $\theta \neq n\pi$ for integer $n$.

Values of Trigonometric Functions at Standard Angles:

The values of trigonometric functions for certain standard angles are the building blocks of trigonometry. These angles, namely $0^\circ, 30^\circ, 45^\circ, 60^\circ,$ and $90^\circ$ (along with their quadrantal counterparts $180^\circ, 270^\circ,$ and $360^\circ$), appear frequently in physics, engineering, and competitive mathematics.

While these values were originally derived using geometric properties of specific triangles (like the Isosceles Right Triangle for $45^\circ$ or the Equilateral Triangle for $30^\circ/60^\circ$), they are best understood today through the Unit Circle coordinates $(x, y)$.

Derivation Logic

For any angle $\theta$, the values are determined as follows:

- $\sin \theta = y$-coordinate of the intersection point on the unit circle.

- $\cos \theta = x$-coordinate of the intersection point on the unit circle.

- $\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x}$ (Slope of the terminal ray).

The following table summarizes the values of the six trigonometric functions for standard angles in both degrees and radians. This table is essential for solving problems in Calculus and Heights & Distances.

| Angle $\theta$ (Degrees) | Angle $\theta$ (Radians) | $\sin \theta$ | $\cos \theta$ | $\tan \theta$ | $\text{cosec} \theta$ | $\sec \theta$ | $\cot \theta$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $0^\circ$ | $0$ | $0$ | $1$ | $0$ | Undefined | $1$ | Undefined |

| $30^\circ$ | $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $\frac{1}{2}$ | $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$ | $2$ | $\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$ | $\sqrt{3}$ |

| $45^\circ$ | $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$ | $1$ | $\sqrt{2}$ | $\sqrt{2}$ | $1$ |

| $60^\circ$ | $\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$ | $\frac{1}{2}$ | $\sqrt{3}$ | $\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$ | $2$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$ |

| $90^\circ$ | $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $1$ | $0$ | Undefined | $1$ | Undefined | $0$ |

| $180^\circ$ | $\pi$ | $0$ | $-1$ | $0$ | Undefined | $-1$ | Undefined |

| $270^\circ$ | $\frac{3\pi}{2}$ | $-1$ | $0$ | Undefined | $-1$ | Undefined | $0$ |

| $360^\circ$ | $2\pi$ | $0$ | $1$ | $0$ | Undefined | $1$ | Undefined |

Notes on Undefined Values:

In competitive exams, understanding why a value is undefined is as important as knowing the value itself. Undefined states occur when the denominator of a trigonometric ratio becomes zero.

Case 1: Vertical Terminal Side ($\cos \theta = 0$)

When the terminal side of the angle $\theta$ lies on the Y-axis (at $90^\circ, 270^\circ,$ etc.), the x-coordinate is zero. This makes functions with $\cos \theta$ in the denominator undefined.

$\tan \theta = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}$ and $\sec \theta = \frac{1}{\cos \theta}$

[Undefined at $\cos \theta = 0$]

General Condition:

$\theta = (2n + 1)\frac{\pi}{2}$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

Case 2: Horizontal Terminal Side ($\sin \theta = 0$)

When the terminal side of the angle $\theta$ lies on the X-axis (at $0^\circ, 180^\circ, 360^\circ,$ etc.), the y-coordinate is zero. This makes functions with $\sin \theta$ in the denominator undefined.

$\cot \theta = \frac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}$ and $\text{cosec} \theta = \frac{1}{\sin \theta}$

[Undefined at $\sin \theta = 0$]

General Condition:

$\theta = n\pi$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

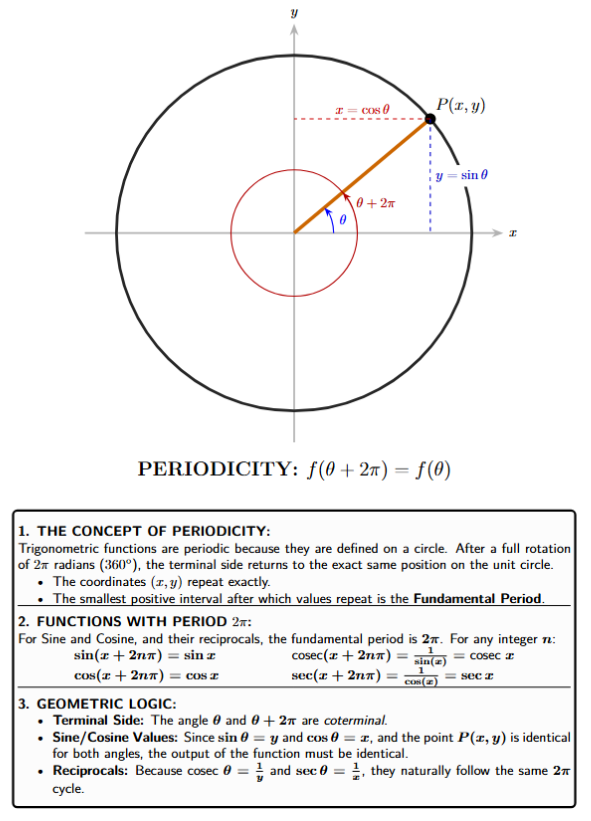

Periodicity of Trigonometric Functions

A function $f(x)$ is defined as periodic if there exists a positive real number $T$ such that $f(x + T) = f(x)$ for all $x$ in the domain. The smallest such value of $T$ is called the fundamental period. This property is a direct consequence of the circular nature of trigonometric definitions.

When an angle $\theta$ completes one full revolution ($2\pi$ radians or $360^\circ$), the terminal side returns to its original position. Consequently, the coordinates $(x, y)$ on the unit circle repeat their values.

1. Sine, Cosine, Cosecant, and Secant (Period $2\pi$)

For the Sine and Cosine functions, the values repeat only after a full rotation. Since Cosecant and Secant are their reciprocals, they share the same period.

For any integer $n \in \mathbb{Z}$:

$\sin(x + 2n\pi) = \sin x$

$\cos(x + 2n\pi) = \cos x$

$\text{cosec}(x + 2n\pi) = \text{cosec } x$

$\sec(x + 2n\pi) = \sec x$

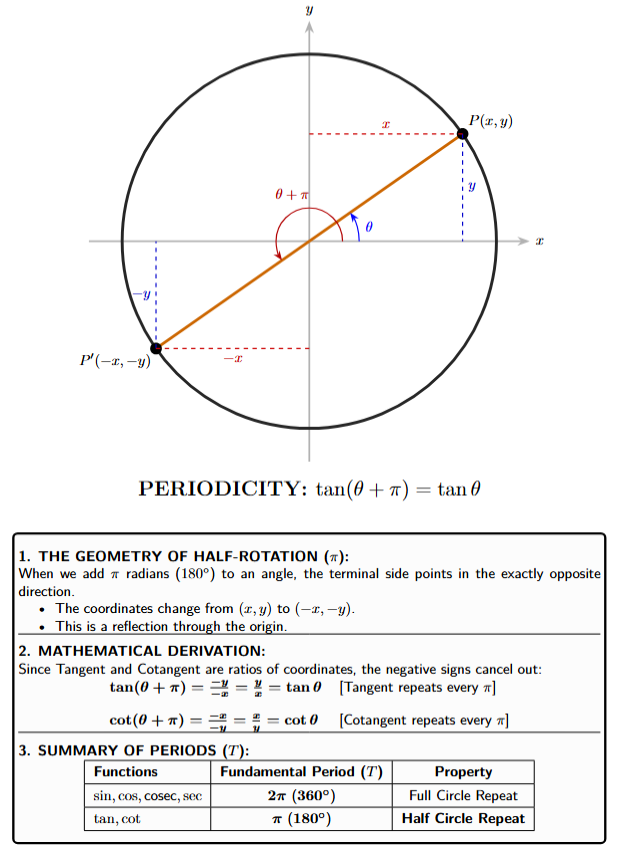

2. Tangent and Cotangent (Period $\pi$)

The Tangent and Cotangent functions repeat more frequently. If an angle $x$ corresponds to point $P(x, y)$, adding half a rotation ($\pi$ radians) results in the point $P'(-x, -y)$.

Derivation of Tangent Periodicity

By definition, $\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x}$. Let's calculate the tangent for $(x + \pi)$:

$\tan(x + \pi) = \frac{-y}{-x}$

[Coordinates of diametrically opposite point]

$\tan(x + \pi) = \frac{y}{x} = \tan x$

Thus, the values of tangent and cotangent repeat every $\pi$ radians ($180^\circ$):

$\tan(x + n\pi) = \tan x$

$\cot(x + n\pi) = \cot x$

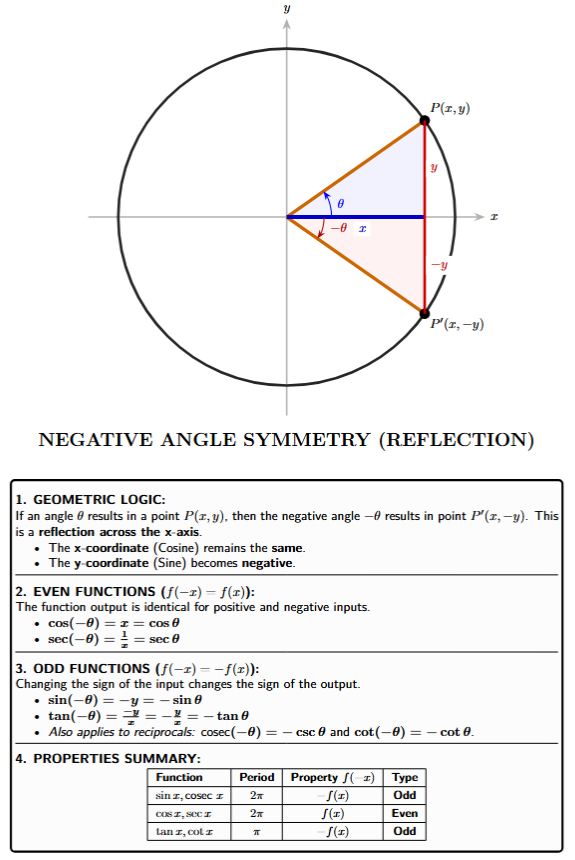

Trigonometric Functions for Negative Angles (Even and Odd Properties)

The Even-Odd properties of trigonometric functions describe how they behave when the sign of the input angle is changed. Geometrically, if $\theta$ is a point $P(x, y)$ on the unit circle, then $-\theta$ is its reflection across the x-axis, point $P'(x, -y)$.

Classification of Functions

1. Even Functions ($\cos, \sec$)

A function is even if $f(-x) = f(x)$. On the unit circle, the x-coordinate (cosine) remains unchanged when reflecting across the x-axis.

$\cos(-\theta) = \cos \theta$

[x-coordinate is same]

$\sec(-\theta) = \sec \theta$

2. Odd Functions ($\sin, \tan, \text{cosec}, \cot$)

A function is odd if $f(-x) = -f(x)$. The y-coordinate (sine) changes sign when reflecting across the x-axis.

$\sin(-\theta) = -\sin \theta$

[y-coordinate becomes negative]

$\tan(-\theta) = \frac{\sin(-\theta)}{\cos(-\theta)} = \frac{-\sin \theta}{\cos \theta} = -\tan \theta$

$\text{cosec}(-\theta) = -\text{cosec } \theta$

$\cot(-\theta) = -\cot \theta$

The properties of trigonometric functions regarding their repetition (periodicity) and their behavior with negative angles (even-odd nature) are essential for simplifying complex trigonometric expressions. The table below provides a comprehensive summary of these characteristics for all six functions.

| Function | Fundamental Period (Radians) | Fundamental Period (Degrees) | Negative Angle Property $f(-x)$ | Function Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\sin x$ | $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $-\sin x$ | Odd |

| $\cos x$ | $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $\cos x$ | Even |

| $\tan x$ | $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $-\tan x$ | Odd |

| $\text{cosec } x$ | $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $-\text{cosec } x$ | Odd |

| $\sec x$ | $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $\sec x$ | Even |

| $\cot x$ | $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $-\cot x$ | Odd |

Graph of Trigonometric Functions

The visual representation of trigonometric functions provides a profound understanding of their periodic nature and behavior across the set of real numbers. These graphs are essential for solving complex engineering, physics, and mathematical problems, especially those involving wave motion and oscillations. A trigonometric graph maps the input angle $x$ (usually in radians) on the horizontal axis and the functional value $f(x)$ on the vertical axis.

All trigonometric functions are periodic, meaning their values repeat after a specific interval known as the period. Mathematically, a function $f$ is periodic if there exists a positive real number $T$ such that:

$f(x + T) = f(x)$

[For all $x$ in domain]

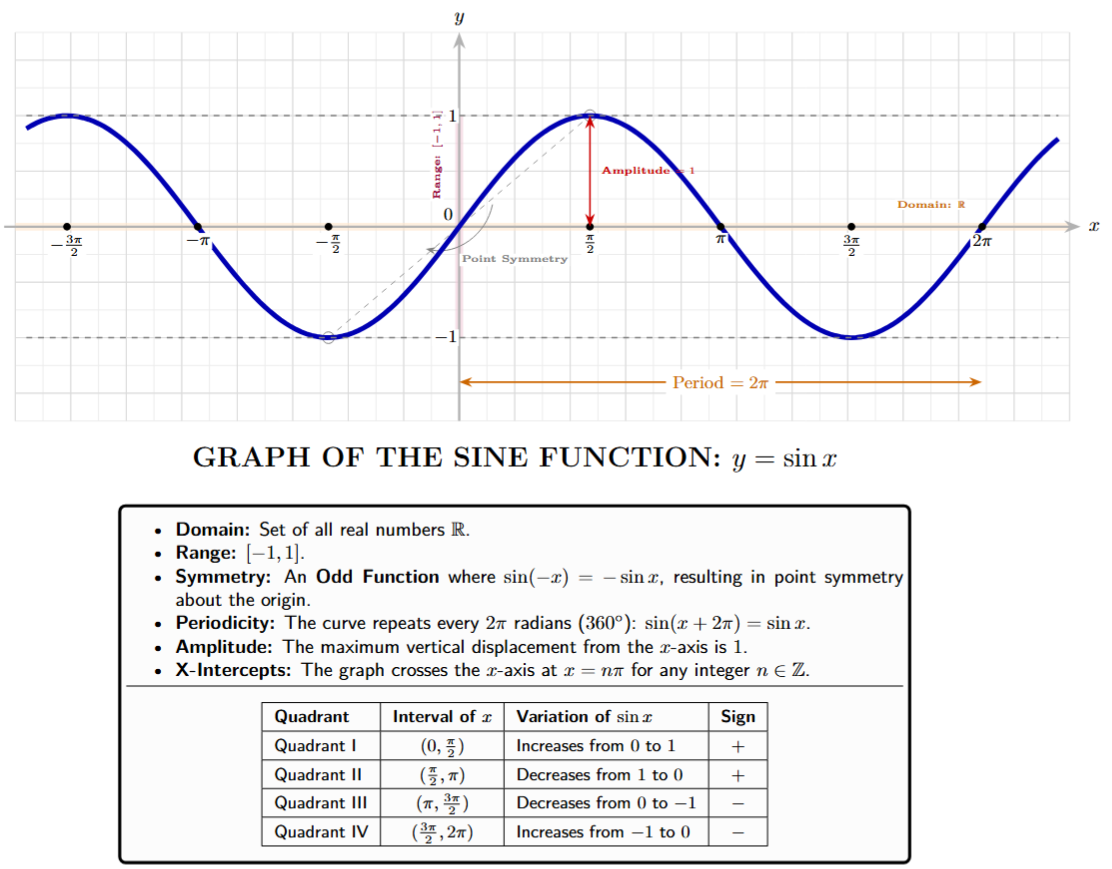

1. Graph of $y = \sin x$:

The sine function is the most basic periodic oscillation. It is derived from the unit circle, where for any point $P(x, y)$ on a circle of radius $1$ centered at the origin, the $y$-coordinate represents the sine of the angle $\theta$ formed with the positive x-axis.

Derivation and Conceptual Origin

Consider a unit circle $x^2 + y^2 = 1$. As a point moves counter-clockwise along the circumference, the vertical height ($y$) varies. Since the maximum height is $1$ and the minimum is $-1$, the function is naturally bounded.

$y = \sin x$

[Defining the ordinate]

Fundamental Properties of $y = \sin x$

(i) Domain: Since the sine function is defined for every possible rotation (angle), its domain is the set of all real numbers.

Domain $= (-\infty, \infty)$ or $\mathbb{R}$.

(ii) Range: On a unit circle, the y-coordinate never exceeds $1$ and never drops below $-1$.

Range $= [-1, 1]$

(iii) Periodicity: The sine function completes one full cycle every $2\pi$ radians ($360^\circ$).

$\sin(x + 2n\pi) = \sin x$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

(iv) Amplitude: The amplitude is the maximum displacement from the equilibrium (x-axis). For $y = \sin x$, the amplitude is $1$.

(v) Odd Nature (Symmetry): The sine function is an odd function, meaning it is symmetric with respect to the origin.

$\sin(-x) = -\sin x$

Table of Key Values for $y = \sin x$

To plot the graph accurately, we observe the values of $\sin x$ at critical intervals within the first period $[0, 2\pi]$.

| $x$ (Radians) | $x$ (Degrees) | $y = \sin x$ |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $30^\circ$ | $0.5$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $45^\circ$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.707$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $60^\circ$ | $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \approx 0.866$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $90^\circ$ | $1$ (Max Value) |

| $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $\frac{3\pi}{2}$ | $270^\circ$ | $-1$ (Min Value) |

| $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $0$ |

Behavior in Different Quadrants

The behavior of the sine graph changes as $x$ moves through the four quadrants:

| Quadrant | Range of $x$ | Variation of $\sin x$ |

|---|---|---|

| I | $(0, \frac{\pi}{2})$ | Increases from $0$ to $1$ |

| II | $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$ | Decreases from $1$ to $0$ |

| III | $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$ | Decreases from $0$ to $-1$ |

| IV | $(\frac{3\pi}{2}, 2\pi)$ | Increases from $-1$ to $0$ |

Graphical Representation

The resulting curve is known as a Sinusoid. It is continuous and differentiable everywhere in its domain.

Example 1. Find the value of $\sin(750^\circ)$.

Answer:

We know that the sine function has a period of $360^\circ$. Any angle can be written in the form $(n \times 360^\circ + \theta)$.

Given: Angle $= 750^\circ$

We can express $750^\circ$ as:

$750^\circ = 2 \times 360^\circ + 30^\circ$

Using the property $\sin(n \times 360^\circ + \theta) = \sin \theta$:

$\sin(750^\circ) = \sin(2 \times 360^\circ + 30^\circ)$

$\sin(750^\circ) = \sin(30^\circ)$

From the standard values table:

$\sin(30^\circ) = \frac{1}{2}$

Final Answer: The value of $\sin(750^\circ)$ is $0.5$.

2. Graph of $y = \cos x$:

The cosine function is a periodic oscillation that, much like the sine function, is derived from the unit circle. For any point $P(x, y)$ on a circle of radius $1$ centered at the origin, the x-coordinate represents the cosine of the angle $\theta$ formed with the positive x-axis. In the context of waves, the cosine graph is often referred to as a cosinusoid.

Derivation and Conceptual Origin

Consider a unit circle $x^2 + y^2 = 1$. As a point moves counter-clockwise along the circumference, the horizontal distance from the y-axis ($x$) varies. Since the circle has a radius of $1$, the maximum horizontal displacement is $1$ and the minimum is $-1$.

$y = \cos x$

[Defining the abscissa]

Fundamental Properties of $y = \cos x$

(i) Domain: The cosine function is defined for every real number angle. Thus, Domain $= \mathbb{R}$ or $(-\infty, \infty)$.

(ii) Range: Similar to the sine function, the output values are bounded by the unit circle's radius. Hence, Range $= [-1, 1]$.

(iii) Periodicity: The cosine function completes one full cycle every $2\pi$ radians ($360^\circ$).

$\cos(x + 2n\pi) = \cos x$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

(iv) Amplitude: The amplitude is the maximum displacement from the x-axis. For $y = \cos x$, the amplitude is $1$.

(v) Even Nature (Symmetry): Unlike the sine function, the cosine function is an even function. Its graph is symmetric with respect to the y-axis.

$\cos(-x) = \cos x$

Table of Key Values for $y = \cos x$

To plot the graph accurately, we observe the values of $\cos x$ at critical intervals within the first period $[0, 2\pi]$.

| $x$ (Radians) | $x$ (Degrees) | $y = \cos x$ |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0^\circ$ | $1$ (Max Value) |

| $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $30^\circ$ | $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \approx 0.866$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $45^\circ$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.707$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $60^\circ$ | $0.5$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $90^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $-1$ (Min Value) |

| $\frac{3\pi}{2}$ | $270^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $1$ |

Behavior in Different Quadrants

The behavior of the cosine graph changes as $x$ moves through the four quadrants:

| Quadrant | Range of $x$ | Variation of $\cos x$ |

|---|---|---|

| I | $(0, \frac{\pi}{2})$ | Decreases from $1$ to $0$ |

| II | $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$ | Decreases from $0$ to $-1$ |

| III | $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$ | Increases from $-1$ to $0$ |

| IV | $(\frac{3\pi}{2}, 2\pi)$ | Increases from $0$ to $1$ |

Comparison between Sine and Cosine Graphs

In competitive exams, understanding the relationship between $\sin x$ and $\cos x$ is crucial for solving transformation problems. The two functions are related by a horizontal shift of $\frac{\pi}{2}$ radians ($90^\circ$).

1. Phase Relationship: The cosine function leads the sine function by $\pi/2$.

$\cos x = \sin\left(x + \frac{\pi}{2}\right)$

$\sin x = \cos\left(x - \frac{\pi}{2}\right)$

2. Intersections: Within the interval $[0, 2\pi]$, the graphs of $\sin x$ and $\cos x$ intersect at two points where their values are equal:

$x = \frac{\pi}{4}$ (both are $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$) and $x = \frac{5\pi}{4}$ (both are $-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$).

Graphical Representation

The resulting curve is smooth and continuous. Unlike the sine graph which starts at $(0,0)$, the cosine graph starts at its maximum value $(0,1)$.

Example 1. Find the value of $\cos(480^\circ)$.

Answer:

We know that the cosine function has a period of $360^\circ$. Any angle can be written in the form $(n \times 360^\circ + \theta)$.

Given: Angle $= 480^\circ$

We can express $480^\circ$ as:

$480^\circ = 1 \times 360^\circ + 120^\circ$

Using the property $\cos(n \times 360^\circ + \theta) = \cos \theta$:

$\cos(480^\circ) = \cos(120^\circ)$

Now, $\cos(120^\circ)$ can be written using the quadrant rule ($\cos(180^\circ - \theta) = -\cos \theta$):

$\cos(120^\circ) = \cos(180^\circ - 60^\circ)$

$\cos(120^\circ) = -\cos(60^\circ)$

From the standard values table:

$\cos(60^\circ) = \frac{1}{2}$

Final Answer: The value of $\cos(480^\circ)$ is $-0.5$.

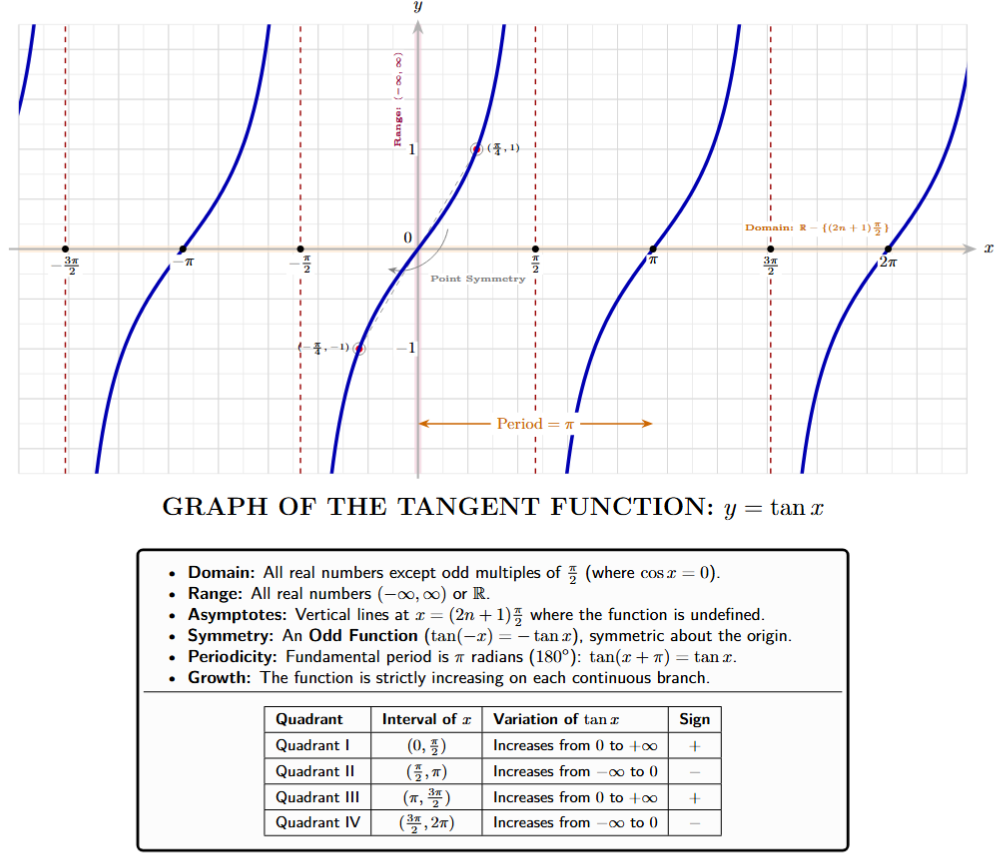

3. Graph of $y = \tan x$:

The tangent function, denoted as $y = \tan x$, represents a fundamentally different periodic behavior compared to the sine and cosine functions. While sine and cosine are smooth, continuous waves bounded between $-1$ and $1$, the tangent function is discontinuous and spans the entire set of real numbers from negative infinity to positive infinity.

Derivation and Conceptual Origin

The tangent function is analytically defined as the ratio of the sine function to the cosine function. In the unit circle, if a point $P(x, y)$ makes an angle $x$ with the positive x-axis, then:

$\tan x = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x}$

[Ratio Identity]

Because the denominator contains $\cos x$, the function becomes undefined whenever $\cos x = 0$. This occurs at odd multiples of $\frac{\pi}{2}$ (i.e., $\pm \frac{\pi}{2}, \pm \frac{3\pi}{2}, ...$).

Fundamental Properties of $y = \tan x$

(i) Domain: The domain includes all real numbers except those where the cosine is zero.

Domain $= \mathbb{R} - \{(2n + 1)\frac{\pi}{2} : n \in \mathbb{Z} \}$

(ii) Range: Unlike sine, the tangent function is not bounded. It covers all real values.

Range $= (-\infty, \infty)$ or $\mathbb{R}$.

(iii) Periodicity: The tangent function repeats much faster than sine or cosine. Its fundamental period is $\pi$ radians ($180^\circ$).

$\tan(x + n\pi) = \tan x$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

(iv) Asymptotes: The graph features vertical lines called asymptotes at $x = (2n+1)\frac{\pi}{2}$. The curve approaches these lines but never touches them.

(v) Odd Nature (Symmetry): The tangent function is an odd function, making it symmetric with respect to the origin.

$\tan(-x) = -\tan x$

Table of Key Values for $y = \tan x$

To plot the graph, we observe the values within the primary interval $(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2})$:

| $x$ (Radians) | $x$ (Degrees) | $y = \tan x$ |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $30^\circ$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \approx 0.577$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $45^\circ$ | $1$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $60^\circ$ | $\sqrt{3} \approx 1.732$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $90^\circ$ | $\infty$ (Not Defined) |

| $\frac{2\pi}{3}$ | $120^\circ$ | $-\sqrt{3}$ |

| $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $0$ |

Behavior in Different Quadrants

The variation of $\tan x$ depends on the signs of $\sin x$ and $\cos x$ in each quadrant:

| Quadrant | Range of $x$ | Variation of $\tan x$ |

|---|---|---|

| I (All) | $(0, \frac{\pi}{2})$ | Increases from $0$ to $\infty$ |

| II (Sine) | $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$ | Increases from $-\infty$ to $0$ |

| III (Tan) | $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$ | Increases from $0$ to $\infty$ |

| IV (Cos) | $(\frac{3\pi}{2}, 2\pi)$ | Increases from $-\infty$ to $0$ |

Graphical Representation

The tangent graph consists of infinitely many separate branches. Each branch is strictly increasing. The points where the graph crosses the x-axis ($y=0$) are $x = n\pi$.

Example 1. Evaluate the value of $\tan(225^\circ)$.

Answer:

We use the periodicity and quadrant rules for the tangent function.

Given: Angle $= 225^\circ$

Since the angle lies in the Third Quadrant ($180^\circ < 225^\circ < 270^\circ$), we know that $\tan x$ is positive here.

We can express $225^\circ$ as:

$225^\circ = 180^\circ + 45^\circ$

Using the reduction formula $\tan(180^\circ + \theta) = \tan \theta$:

$\tan(225^\circ) = \tan(45^\circ)$

From the standard values table:

$\tan(45^\circ) = 1$

Final Answer: The value of $\tan(225^\circ)$ is $1$.

Example 2. Find the number of solutions for $\tan x = \sqrt{3}$ in the interval $[0, 2\pi]$.

Answer:

The tangent function is positive in the First and Third quadrants.

Quadrant I:

$\tan x = \sqrt{3} \implies x = 60^\circ = \frac{\pi}{3}$

Quadrant III:

$\tan x = \tan(\pi + \frac{\pi}{3}) = \tan(\frac{4\pi}{3})$

$x = \frac{4\pi}{3}$

Conclusion: There are $2$ solutions in the given interval.

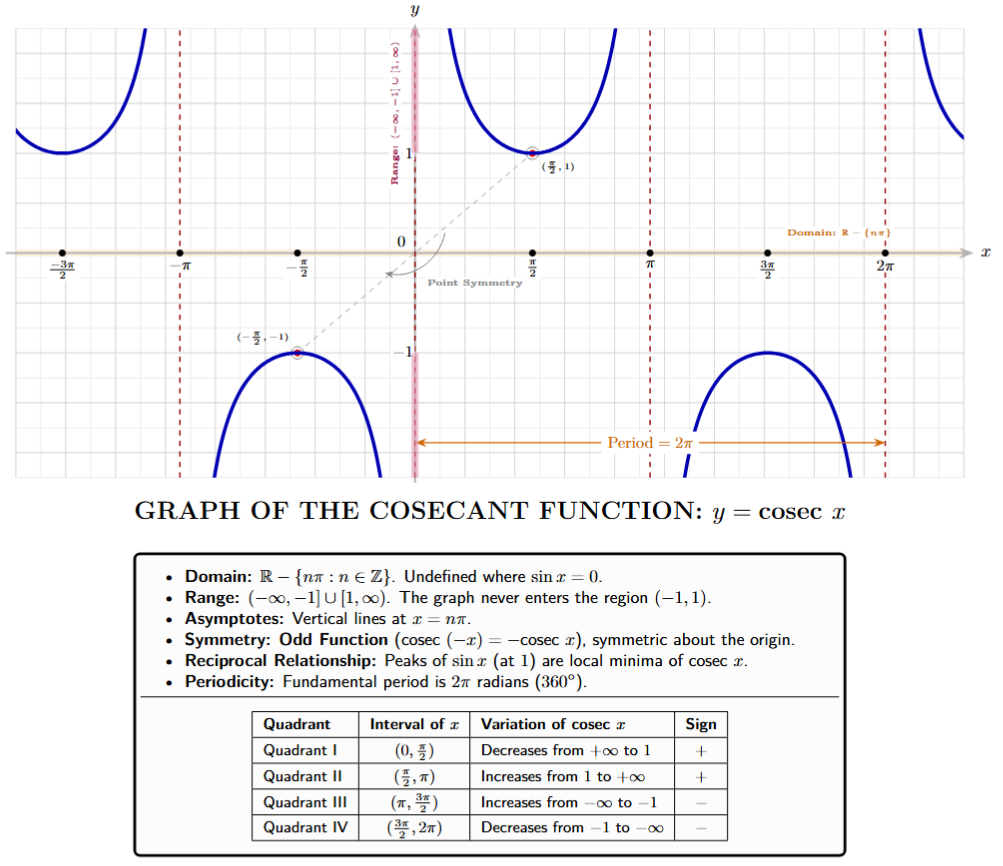

4. Graph of $y = \text{cosec } x$:

The cosecant function, denoted as $y = \text{cosec } x$, is the reciprocal of the sine function. Because it is derived from the reciprocal of $\sin x$, its graphical behavior is significantly different from the smooth sinusoidal waves. The values of $\text{cosec } x$ are entirely dependent on the values of $\sin x$, leading to a graph characterized by U-shaped curves (often called branches) and vertical asymptotes.

Derivation and Conceptual Origin

The cosecant function is analytically defined as follows:

$y = \text{cosec } x = \frac{1}{\sin x}$

[Reciprocal Identity]

Since division by zero is undefined, the function $y = \text{cosec } x$ does not exist at points where $\sin x = 0$. These points occur at all integer multiples of $\pi$ (i.e., $0, \pm \pi, \pm 2\pi, \dots$).

Fundamental Properties of $y = \text{cosec } x$

(i) Domain: The domain includes all real numbers except where the sine function vanishes.

Domain $= \mathbb{R} - \{n\pi : n \in \mathbb{Z} \}$

(ii) Range: Since $|\sin x| \leq 1$, its reciprocal must have an absolute value greater than or equal to $1$.

Range $= (-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)$

(iii) Periodicity: Like the sine function, the cosecant function repeats its values every $2\pi$ radians ($360^\circ$).

$\text{cosec}(x + 2n\pi) = \text{cosec } x$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

(iv) Asymptotes: The graph contains vertical asymptotes at $x = n\pi$. These are the lines the graph approaches but never touches.

(v) Odd Nature (Symmetry): Since sine is an odd function, its reciprocal is also an odd function. The graph is symmetric with respect to the origin.

$\text{cosec}(-x) = -\text{cosec } x$

Table of Key Values for $y = \text{cosec } x$

To plot the graph, we observe the values within the interval $(0, 2\pi)$:

| $x$ (Radians) | $x$ (Degrees) | $y = \text{cosec } x$ |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0^\circ$ | $\infty$ (Undefined) |

| $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $30^\circ$ | $2$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $45^\circ$ | $\sqrt{2} \approx 1.414$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $90^\circ$ | $1$ (Local Minimum) |

| $\frac{5\pi}{6}$ | $150^\circ$ | $2$ |

| $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $\pm \infty$ (Undefined) |

| $\frac{3\pi}{2}$ | $270^\circ$ | $-1$ (Local Maximum) |

Behavior in Different Quadrants

The sign of $\text{cosec } x$ follows the same "ASTC" rule as $\sin x$:

| Quadrant | Interval | Variation of $\text{cosec } x$ |

|---|---|---|

| I | $(0, \frac{\pi}{2})$ | Decreases from $\infty$ to $1$ |

| II | $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$ | Increases from $1$ to $\infty$ |

| III | $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$ | Increases from $-\infty$ to $-1$ |

| IV | $(\frac{3\pi}{2}, 2\pi)$ | Decreases from $-1$ to $-\infty$ |

Relationship with the Sine Graph

When studying for competitive exams, it is helpful to visualize the sine and cosecant graphs together:

1. At every point where $\sin x = 1$ (the peaks), $\text{cosec } x = 1$.

2. At every point where $\sin x = -1$ (the troughs), $\text{cosec } x = -1$.

3. As $\sin x$ gets closer to $0$, $\text{cosec } x$ shoots off toward positive or negative infinity.

Graphical Representation

The graph consists of alternating upward and downward opening curves. It never crosses the x-axis, meaning $\text{cosec } x = 0$ has no real solutions.

Example 1. Evaluate the value of $\text{cosec}(-330^\circ)$.

Answer:

We apply the odd function property and periodicity.

Step 1: Use the property $\text{cosec}(-x) = -\text{cosec } x$.

$\text{cosec}(-330^\circ) = -\text{cosec}(330^\circ)$

Step 2: Use the quadrant rule. $330^\circ$ is in the Fourth Quadrant.

$330^\circ = 360^\circ - 30^\circ$

$\text{cosec}(360^\circ - \theta) = -\text{cosec } \theta$

Step 3: Substitute the values.

$\text{cosec}(-330^\circ) = -(-\text{cosec } 30^\circ)$

$\text{cosec}(-330^\circ) = \text{cosec } 30^\circ$

From standard values, $\sin 30^\circ = 1/2$, so $\text{cosec } 30^\circ = 2$.

Final Answer: The value is $2$.

Example 2. Determine the range of the function $f(x) = 3 \text{cosec } x + 2$.

Answer:

We know the standard range of $\text{cosec } x$ is $(-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)$.

Case 1: When $\text{cosec } x \geq 1$

$3 \text{cosec } x \geq 3$

$3 \text{cosec } x + 2 \geq 5$

Case 2: When $\text{cosec } x \leq -1$

$3 \text{cosec } x \leq -3$

$3 \text{cosec } x + 2 \leq -1$

Final Range: $(-\infty, -1] \cup [5, \infty)$.

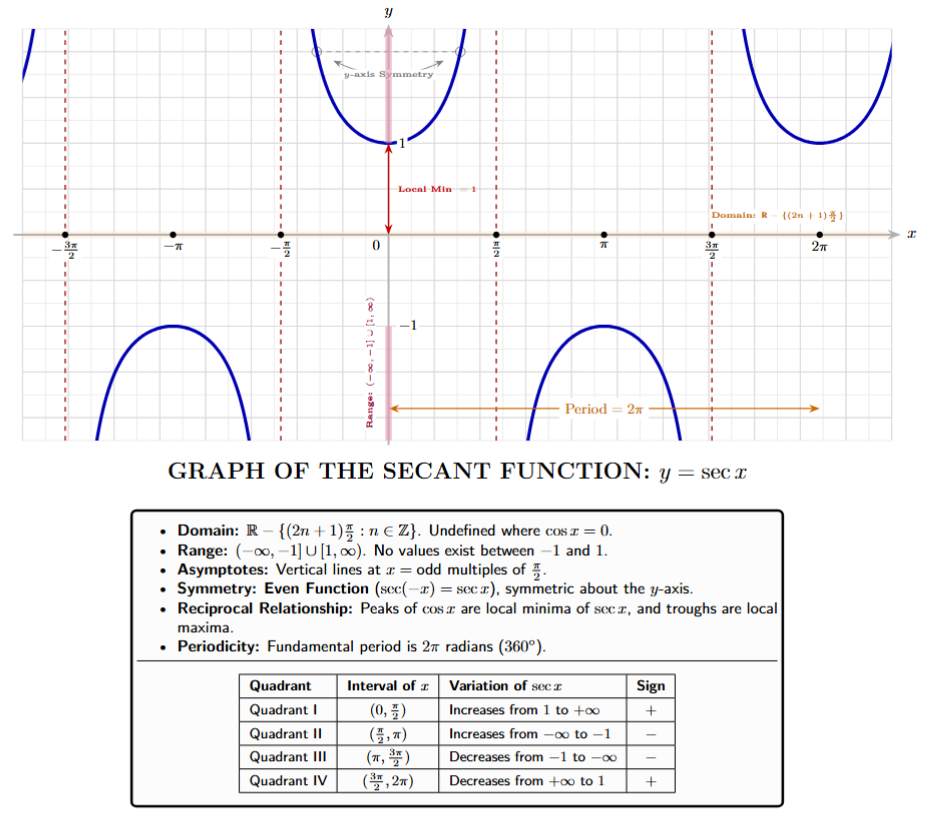

5. Graph of $y = \sec x$:

The secant function, denoted as $y = \sec x$, is defined as the reciprocal of the cosine function. Its behavior is intrinsically linked to the cosine wave, but instead of being bounded, it extends to infinity. The graph of the secant function is characterized by a series of alternating parabolic-like branches separated by vertical asymptotes.

Derivation and Conceptual Origin

The secant function is analytically derived from the reciprocal relationship with cosine:

$y = \sec x = \frac{1}{\cos x}$

[Reciprocal Identity]

This definition implies that the function is undefined whenever $\cos x = 0$. These points occur at odd multiples of $\frac{\pi}{2}$, specifically $x = \dots, -\frac{3\pi}{2}, -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{3\pi}{2}, \dots$.

Fundamental Properties of $y = \sec x$

(i) Domain: The domain includes all real numbers except those where the cosine value is zero.

Domain $= \mathbb{R} - \{(2n + 1)\frac{\pi}{2} : n \in \mathbb{Z} \}$

(ii) Range: Since the maximum value of $|\cos x|$ is $1$, its reciprocal $|\sec x|$ must always be greater than or equal to $1$.

Range $= (-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)$

(iii) Periodicity: The secant function shares the same period as the cosine function.

$\sec(x + 2n\pi) = \sec x$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

(iv) Asymptotes: The graph features vertical asymptotes at $x = (2n+1)\frac{\pi}{2}$. As $x$ approaches these values, $\sec x$ tends toward $\pm\infty$.

(v) Even Nature (Symmetry): Since cosine is an even function, the secant function is also an even function. The graph is symmetric with respect to the y-axis.

$\sec(-x) = \sec x$

Table of Key Values for $y = \sec x$

To plot the graph accurately, we analyze the values within the interval $[0, 2\pi]$:

| $x$ (Radians) | $x$ (Degrees) | $y = \sec x$ |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0^\circ$ | $1$ (Local Minimum) |

| $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $30^\circ$ | $\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \approx 1.15$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $45^\circ$ | $\sqrt{2} \approx 1.414$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $60^\circ$ | $2$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $90^\circ$ | $\infty$ (Undefined) |

| $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $-1$ (Local Maximum) |

| $\frac{3\pi}{2}$ | $270^\circ$ | $\pm \infty$ (Undefined) |

| $2\pi$ | $360^\circ$ | $1$ |

Behavior in Different Quadrants

The sign and growth of $\sec x$ depend on $\cos x$ in the four quadrants:

| Quadrant | Range of $x$ | Variation of $\sec x$ |

|---|---|---|

| I | $(0, \frac{\pi}{2})$ | Increases from $1$ to $\infty$ |

| II | $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$ | Increases from $-\infty$ to $-1$ |

| III | $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$ | Decreases from $-1$ to $-\infty$ |

| IV | $(\frac{3\pi}{2}, 2\pi)$ | Decreases from $\infty$ to $1$ |

Comparison with the Cosine Graph

For a visual and conceptual comparison:

1. At every point where the cosine graph has a peak ($\cos x = 1$), the secant graph has a local minimum ($\sec x = 1$).

2. At every point where the cosine graph has a trough ($\cos x = -1$), the secant graph has a local maximum ($\sec x = -1$).

3. As the cosine value approaches zero, the secant value approaches positive or negative infinity, creating the asymptotic behavior.

Graphical Representation

The resulting graph consists of several U-shaped and inverted U-shaped branches. It exists entirely outside the vertical strip between $y = -1$ and $y = 1$.

Example 1. Find the value of $\sec(420^\circ)$.

Answer:

We use the periodicity and reciprocal properties of the secant function.

Given: Angle $= 420^\circ$

We know that $\sec(n \times 360^\circ + \theta) = \sec \theta$.

$420^\circ = 1 \times 360^\circ + 60^\circ$

Therefore:

$\sec(420^\circ) = \sec(60^\circ)$

Using the reciprocal identity:

$\sec(60^\circ) = \frac{1}{\cos(60^\circ)}$

From the standard values table, $\cos(60^\circ) = \frac{1}{2}$.

$\sec(60^\circ) = \frac{1}{1/2} = 2$

Final Answer: The value of $\sec(420^\circ)$ is $2$.

Example 2. Identify the interval in which $\sec x$ is negative within $[0, 2\pi]$.

Answer:

Since $\sec x = 1/\cos x$, the sign of the secant function is determined by the sign of the cosine function.

Cosine is negative in the Second and Third quadrants.

1. Quadrant II: $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$

2. Quadrant III: $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$

Conclusion: $\sec x < 0$ for $x \in (\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{3\pi}{2})$.

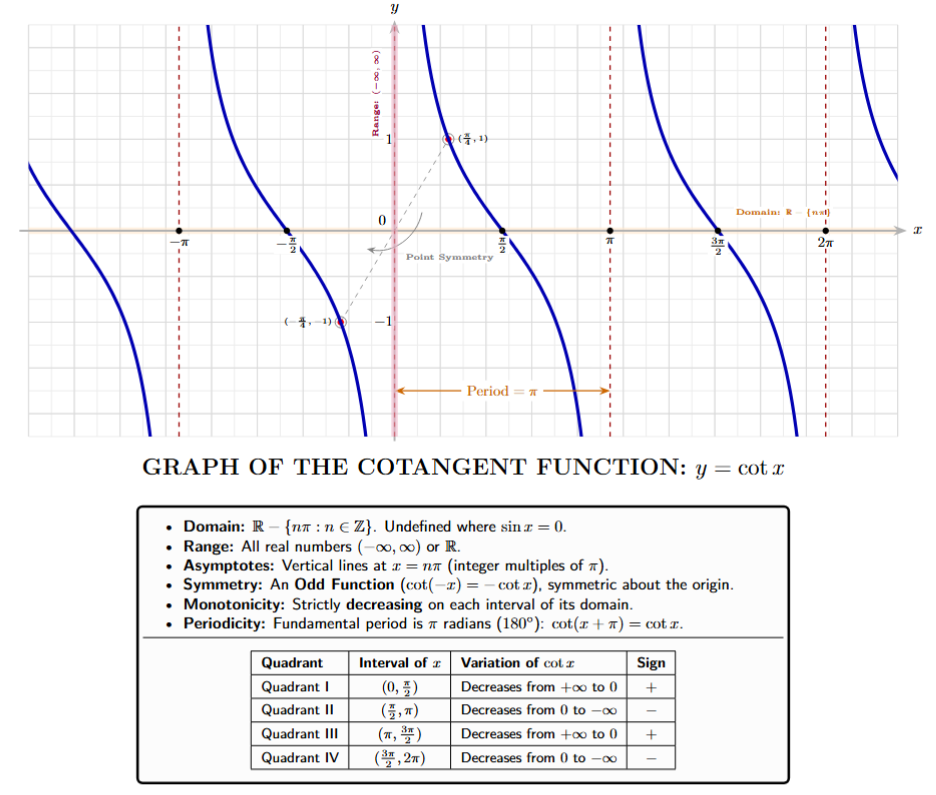

6. Graph of $y = \cot x$:

The cotangent function, denoted as $y = \cot x$, is the reciprocal of the tangent function. While it shares the same periodicity as the tangent function, its graphical structure is reflected and shifted. The cotangent function represents the ratio of the adjacent side to the opposite side in a right-angled triangle, or the ratio of the x-coordinate to the y-coordinate on a unit circle.

Derivation and Conceptual Origin

The cotangent function is analytically defined as the ratio of the cosine function to the sine function. This relationship is expressed as:

$y = \cot x = \frac{\cos x}{\sin x}$

[Ratio Identity]

Alternatively, it is the reciprocal of the tangent function:

$y = \cot x = \frac{1}{\tan x}$

Because the denominator contains $\sin x$, the function becomes undefined whenever $\sin x = 0$. This occurs at all integer multiples of $\pi$ (i.e., $0, \pm\pi, \pm 2\pi, ...$).

Fundamental Properties of $y = \cot x$

(i) Domain: The domain includes all real numbers except the points where the sine function is zero.

Domain $= \mathbb{R} - \{n\pi : n \in \mathbb{Z} \}$.

(ii) Range: Like the tangent function, the cotangent function is not bounded and covers the entire set of real numbers.

Range $= (-\infty, \infty)$ or $\mathbb{R}$.

(iii) Periodicity: The fundamental period of the cotangent function is $\pi$ radians ($180^\circ$).

$\cot(x + n\pi) = \cot x$

[where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$]

(iv) Asymptotes: The graph features vertical asymptotes at $x = n\pi$. The curve approaches these lines but never crosses them.

(v) Odd Nature (Symmetry): The cotangent function is an odd function, making it symmetric with respect to the origin.

$\cot(-x) = -\cot x$

Table of Key Values for $y = \cot x$

To plot the graph, we observe the values within the primary interval $(0, \pi)$:

| $x$ (Radians) | $x$ (Degrees) | $y = \cot x$ |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0^\circ$ | $\pm \infty$ (Undefined) |

| $\frac{\pi}{6}$ | $30^\circ$ | $\sqrt{3} \approx 1.732$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $45^\circ$ | $1$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $60^\circ$ | $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \approx 0.577$ |

| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $90^\circ$ | $0$ |

| $\frac{2\pi}{3}$ | $120^\circ$ | $-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$ |

| $\pi$ | $180^\circ$ | $\pm \infty$ (Undefined) |

Behavior in Different Quadrants

The sign of $\cot x$ depends on the quadrants, following the same rule as $\tan x$ (Positive in I and III):

| Quadrant | Range of $x$ | Variation of $\cot x$ |

|---|---|---|

| I | $(0, \frac{\pi}{2})$ | Decreases from $\infty$ to $0$ |

| II | $(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi)$ | Decreases from $0$ to $-\infty$ |

| III | $(\pi, \frac{3\pi}{2})$ | Decreases from $\infty$ to $0$ |

| IV | $(\frac{3\pi}{2}, 2\pi)$ | Decreases from $0$ to $-\infty$ |

Comparison with the Tangent Graph

For competitive exam aspirants, the following comparisons are crucial:

1. Monotonicity: While $y = \tan x$ is a strictly increasing function on its domain intervals, $y = \cot x$ is a strictly decreasing function on its domain intervals.

2. Asymptotes: The asymptotes of $\tan x$ occur at odd multiples of $\pi/2$, whereas the asymptotes of $\cot x$ occur at integer multiples of $\pi$.

3. Phase Shift: The graphs are related by a horizontal shift and reflection:

$\cot x = \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{2} - x\right)$

Graphical Representation

The cotangent graph consists of several downward-sloping branches. Each branch is separated by a vertical asymptote where the function value shoots to infinity.

Example 1. Evaluate the value of $\cot(135^\circ)$.

Answer:

We use the quadrant reduction rules to find the value.

Given: Angle $= 135^\circ$

Since the angle lies in the Second Quadrant ($90^\circ < 135^\circ < 180^\circ$), we know that $\cot x$ must be negative.

We can express $135^\circ$ in two ways:

Method 1: Using $180^\circ - \theta$

$\cot(135^\circ) = \cot(180^\circ - 45^\circ)$

$\cot(135^\circ) = -\cot(45^\circ)$

Method 2: Using $90^\circ + \theta$

$\cot(135^\circ) = \cot(90^\circ + 45^\circ)$

$\cot(135^\circ) = -\tan(45^\circ)$

From the standard values table, $\cot(45^\circ) = 1$ and $\tan(45^\circ) = 1$.

$\cot(135^\circ) = -1$

Final Answer: The value of $\cot(135^\circ)$ is $-1$.

Example 2. Solve for $x$ in the interval $(0, \pi)$ if $\cot x = -\sqrt{3}$.

Answer:

We need to find the angle $x$ where the cotangent value is $-\sqrt{3}$.

Since the value is negative, and we are looking in the interval $(0, \pi)$, the angle must lie in the Second Quadrant.

We know that in the first quadrant:

$\cot(30^\circ) = \sqrt{3}$ or $\cot\left(\frac{\pi}{6}\right) = \sqrt{3}$

To find the corresponding angle in the second quadrant, we use the formula $\cot(\pi - \theta) = -\cot \theta$:

$x = \pi - \frac{\pi}{6}$

$x = \frac{5\pi}{6}$

Final Answer: The solution is $x = \frac{5\pi}{6}$ (or $150^\circ$).

Summary and Revision Guide: Graphs of Trigonometric Functions

Mastering the visual behavior of trigonometric functions is as important as knowing the identities. A graph allows a student to solve inequalities, find the number of solutions for equations, and understand the limits of a function at a glance. Below is a comprehensive summary, memory aids, and conceptual maps to facilitate quick revision.

Comparison Table of Properties

This table provides a side-by-side comparison of the six trigonometric functions, focusing on the attributes most frequently tested in exams.

| Function | Domain | Range | Period | Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $y = \sin x$ | $\mathbb{R}$ | $[-1, 1]$ | $2\pi$ | Odd |

| $y = \cos x$ | $\mathbb{R}$ | $[-1, 1]$ | $2\pi$ | Even |

| $y = \tan x$ | $\mathbb{R} - \{(2n+1)\frac{\pi}{2}\}$ | $\mathbb{R}$ | $\pi$ | Odd |

| $y = \text{cosec } x$ | $\mathbb{R} - \{n\pi\}$ | $(-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)$ | $2\pi$ | Odd |

| $y = \sec x$ | $\mathbb{R} - \{(2n+1)\frac{\pi}{2}\}$ | $(-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)$ | $2\pi$ | Even |

| $y = \cot x$ | $\mathbb{R} - \{n\pi\}$ | $\mathbb{R}$ | $\pi$ | Odd |

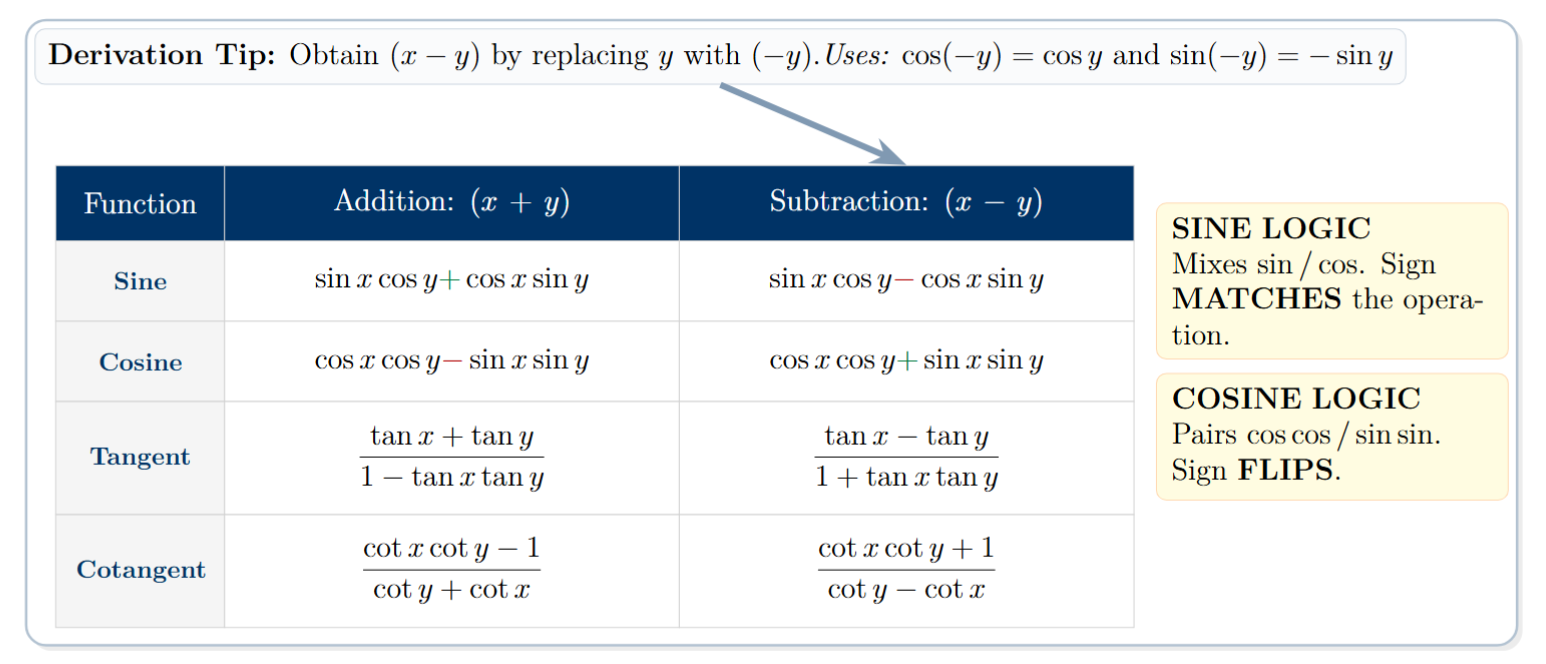

Trigonometric Functions of Sum and Difference

The ability to express trigonometric functions of angles that are the sum or difference of two other angles is essential for simplifying expressions, solving trigonometric equations, and deriving further identities. These formulas are often referred to as compound angle formulas or addition and subtraction formulas.

Fundamental Formulas:

The most fundamental of these formulas are those for the cosine and sine of the sum and difference of two angles.

1. Sine of Sum and Difference of Two Angles:

The addition and subtraction formulas for the sine function are essential tools in trigonometry. While these can be derived algebraically from the cosine identities using co-function properties, a geometric proof provides a clearer visual understanding of how the sine of a compound angle relate to the individual components of the triangles involved.

For any two angles $x$ and $y$, the fundamental sine identities are:

$\sin(x + y) = \sin x \cos y + \cos x \sin y$

…(1)

$\sin(x - y) = \sin x \cos y - \cos x \sin y$

…(2)

Geometric Proof of $\sin(x + y)$

This proof uses a construction involving two right-angled triangles joined together.

Given:

Two acute angles $x$ and $y$ such that their sum $(x + y)$ is also acute.

Construction:

1. Let a ray $OX$ revolve about $O$ to $OY$ to trace angle $y$, i.e., $\angle XOY = y$.

2. Let the ray revolve further from $OY$ to $OZ$ to trace angle $x$, i.e., $\angle YOZ = x$.

3. Thus, the total angle $\angle XOZ = x + y$.

4. Take a point $P$ on the ray $OZ$. Draw $PM \perp OX$ and $PN \perp OY$.

5. From $N$, draw $NR \perp OX$ and $NQ \perp PM$.

Proof:

In the construction, notice that $NQ \parallel OX$. Therefore, $\angle QNO = \angle NOX = y$ (Alternate angles). Also, in $\triangle PQN$, we can determine the angle at $P$:

$\angle QPN = 90^\circ - \angle QNP = y$

[Since $\angle PNO = 90^\circ$]

Now, in $\triangle POM$:

$\sin(x + y) = \frac{PM}{OP}$

[$\frac{\text{Perpendicular}}{\text{Hypotenuse}}$]

We can break the segment $PM$ into two parts: $PQ$ and $QM$.

$\sin(x + y) = \frac{PQ + QM}{OP}$

$\sin(x + y) = \frac{PQ}{OP} + \frac{QM}{OP}$

Since $QNRM$ is a rectangle, $QM = NR$. Substituting this:

$\sin(x + y) = \frac{PQ}{OP} + \frac{NR}{OP}$

... (i)

Now, we manipulate the fractions by multiplying and dividing by the common sides of the triangles:

For the first term, use $PN$ (Hypotenuse of $\triangle PQN$ and Perpendicular of $\triangle PON$):

$\frac{PQ}{OP} = \frac{PQ}{PN} \cdot \frac{PN}{OP} = \cos y \cdot \sin x$

(As $\cos y = \frac{PQ}{PN}$ and $\sin x = \frac{PN}{OP}$)

For the second term, use $ON$ (Hypotenuse of $\triangle ONR$ and Base of $\triangle PON$):

$\frac{NR}{OP} = \frac{NR}{ON} \cdot \frac{ON}{OP} = \sin y \cdot \cos x$

(As $\sin y = \frac{NR}{ON}$ and $\cos x = \frac{ON}{OP}$)

Substituting these back into equation (i):

$\sin(x + y) = (\sin x)(\cos y) + (\cos x)(\sin y)$

$$\sin(x + y) = \sin x \cos y + \cos x \sin y$$

Derivation of $\sin(x - y)$

To derive the formula for $\sin(x - y)$, substitute $-y$ for $y$ in the formula for $\sin(x + y)$

Proof by Substitution:

Replace $y$ with $-y$ in the addition formula:

$\sin(x + (-y)) = \sin x \cos(-y) + \cos x \sin(-y)$

Applying negative angle properties:

$\cos(-y) = \cos y$

[Even Function]

$\sin(-y) = -\sin y$

[Odd Function]

The formula becomes:

$$\sin(x - y) = \sin x \cos y - \cos x \sin y$$

2. Cosine of Sum and Difference of Two Angles:

While many identities exist, the formulas for the cosine of the sum and difference of two angles are considered the fundamental identities because almost all other trigonometric identities can be derived from them.

These formulas allow us to find the exact trigonometric values for angles that are not part of the standard set ($0^\circ, 30^\circ, 45^\circ, 60^\circ, 90^\circ$) by breaking them down into sums or differences of standard angles.

For any real numbers $x$ and $y$ (representing angles in radians):

$\cos(x + y) = \cos x \cos y - \sin x \sin y$

... (3)

$\cos(x - y) = \cos x \cos y + \sin x \sin y$

... (4)

These are central identities from which many others can be derived.

Geometric Derivation of $\cos(x - y)$

To derive the formula for $\cos(x - y)$ as elaborately as possible, we utilize the properties of a Unit Circle (a circle with radius $r = 1$ unit).

Construction Required

1. Draw a unit circle centered at the origin $O(0, 0)$.

2. Let $\angle P_1OX = x$ and $\angle P_2OX = y$.

3. Therefore, the angle $\angle P_1OP_2 = x - y$.

4. Now, consider a point $P_3$ such that $\angle P_3OX = x - y$. Let $P_4$ be the point $(1, 0)$ on the x-axis.

Proof using Distance Formula

By the definition of coordinates on a unit circle, the coordinates of the points are:

- $P_1 = (\cos x, \sin x)$

- $P_2 = (\cos y, \sin y)$

- $P_3 = (\cos(x - y), \sin(x - y))$

- $P_4 = (1, 0)$

Since the angle between $OP_1$ and $OP_2$ is the same as the angle between $OP_3$ and $OP_4$ (both are $x - y$), the chord lengths $P_1P_2$ and $P_3P_4$ must be equal.

$P_1P_2 = P_3P_4$

(Chords subtending equal angles)

Applying the Distance Formula, $d = \sqrt{(x_2-x_1)^2 + (y_2-y_1)^2}$, and squaring both sides:

$(P_1P_2)^2 = (P_3P_4)^2$

Expanding the left side ($P_1P_2$):

$LHS = (\cos x - \cos y)^2 + (\sin x - \sin y)^2$

$LHS = (\cos^2 x - 2\cos x \cos y + \cos^2 y) + (\sin^2 x - 2\sin x \sin y + \sin^2 y)$

Using the identity $\sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta = 1$:

$LHS = (\cos^2 x + \sin^2 x) + (\cos^2 y + \sin^2 y) - 2\cos x \cos y - 2\sin x \sin y$

$LHS = 2 - 2(\cos x \cos y + \sin x \sin y)$

[Simplifying constants]

Expanding the right side ($P_3P_4$):

$RHS = (\cos(x - y) - 1)^2 + (\sin(x - y) - 0)^2$

$RHS = \cos^2(x - y) - 2\cos(x - y) + 1 + \sin^2(x - y)$

$RHS = (\cos^2(x - y) + \sin^2(x - y)) + 1 - 2\cos(x - y)$

$RHS = 2 - 2\cos(x - y)$

[Using Pythagorean identity]

Now, equating equation $LHS$ and $RHS$:

$2 - 2\cos(x - y) = 2 - 2(\cos x \cos y + \sin x \sin y)$

Subtracting $2$ from both sides and dividing by $-2$:

$$\cos(x - y) = \cos x \cos y + \sin x \sin y$$

Derivation of $\cos(x + y)$

The sum formula is derived algebraically using the difference formula by substituting $y$ with $-y$.

Proof

We know that:

$\cos(x + y) = \cos(x - (-y))$

Applying the formula for $\cos(A - B)$ where $A = x$ and $B = -y$:

$\cos(x - (-y)) = \cos x \cos(-y) + \sin x \sin(-y)$

Using the properties of Negative Angles:

$\cos(-y) = \cos y$

(Even function)

$\sin(-y) = -\sin y$

(Odd function)

Substituting these back into the expression:

$\cos(x + y) = \cos x (\cos y) + \sin x (-\sin y)$

$$\cos(x + y) = \cos x \cos y - \sin x \sin y$$

3. Tangent of Sum and Difference of Two Angles:

We can derive the formulas for the tangent of sum and difference using the identity $\tan \theta = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}$ and the formulas for sine and cosine sums/differences.

Derivation of $\tan(x+y)$:

$\tan(x + y) = \frac{\sin(x + y)}{\cos(x + y)}$

Substitute the formulas for $\sin(x+y)$ and $\cos(x+y)$:

$= \frac{\sin x \cos y + \cos x \sin y}{\cos x \cos y - \sin x \sin y}$

To express this in terms of $\tan x$ and $\tan y$, divide the numerator and the denominator by $\cos x \cos y$, assuming $\cos x \neq 0$ and $\cos y \neq 0$:

$= \frac{\frac{\sin x \cos y}{\cos x \cos y} + \frac{\cos x \sin y}{\cos x \cos y}}{\frac{\cos x \cos y}{\cos x \cos y} - \frac{\sin x \sin y}{\cos x \cos y}}$

Simplify the terms (e.g., $\frac{\sin x \cos y}{\cos x \cos y} = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} = \tan x$):

$\tan(x + y) = \frac{\tan x + \tan y}{1 - \tan x \tan y}$

... (5)

This formula is valid when $\cos x \neq 0$, $\cos y \neq 0$, and $\cos(x+y) \neq 0$.

$$\tan(x + y) = \frac{\tan x + \tan y}{1 - \tan x \tan y}$$

Derivation of $\tan(x-y)$: