| Classwise Concept with Examples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

| Content On This Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Point, Line and Plane | Line Segment & Ray | Angle - Interior and Exterior |

| Open and Closed Curves | Polygon & Various Types of Polygon | Circle and Terms Associated With a Circle |

Chapter 4 Basic Geometrical Ideas (Concepts)

Welcome to the fascinating world of Chapter 4: Basic Geometrical Ideas! Geometry is the branch of mathematics that studies shapes, sizes, positions of figures, and properties of space. Think about the shapes you see every day – the roundness of a ball, the straight edge of a book, the corners of a room. Geometry helps us describe and understand these shapes in a precise way. This chapter is incredibly important because it introduces the fundamental building blocks and the special language we use to talk about geometry. We will start with the simplest ideas and gradually build up our understanding, learning the names and definitions of basic geometric elements. Mastering this vocabulary is like learning the alphabet before you can read – it's essential for exploring all the amazing shapes and patterns that exist in the world around us and in mathematics.

Our journey begins with the most basic concept: a point. Imagine the tiniest dot you can make; a point represents an exact location or position in space, but it has no size – no length, width, or thickness. We usually represent it with a capital letter, like point A. If we connect two points using the shortest possible path, we get a line segment. A line segment has two definite endpoints and a fixed length that we can measure. We denote it as $\overline{AB}$. Now, imagine extending this segment infinitely in both directions, never stopping – that gives us a line. A line has no endpoints and goes on forever. We often name it with a lowercase letter like 'l' or using two points on it, like $\overleftrightarrow{AB}$. What if we start at a point and extend infinitely in only one direction? That's a ray, like a beam of sunlight starting from the sun. It has one starting point (endpoint) and continues forever in the other direction, denoted as $\overrightarrow{PQ}$.

Lines in a flat surface can interact in specific ways. When two lines cross each other, they are called intersecting lines, and they meet at exactly one point. Think of the crossing roads. Lines that lie in the same plane but never meet, no matter how far they are extended, are called parallel lines. They always maintain the same distance apart, like the opposite edges of a ruler or railway tracks. Moving beyond straight paths, we encounter curves. Some curves are open curves (they don't end where they started), while others are closed curves (they form a loop, ending back at the starting point). A special type of simple closed curve made entirely of line segments is called a polygon. Familiar shapes like triangles and squares are polygons.

Polygons have specific parts we need to know:

- The line segments forming the polygon are called its sides.

- The points where the sides meet are called vertices (singular: vertex).

- Sides that share a common vertex are adjacent sides.

- Vertices that are endpoints of the same side are adjacent vertices.

- A line segment connecting two non-adjacent vertices is called a diagonal.

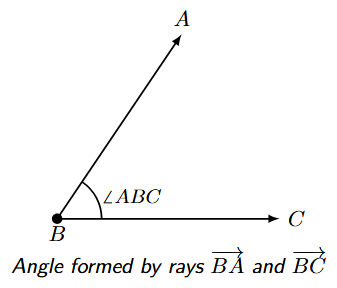

When two rays share a common starting point (vertex), they form an angle. The rays are called the arms of the angle, and the common endpoint is the vertex of the angle. We can name an angle using three letters, with the vertex in the middle (e.g., $\angle ABC$), or sometimes just by its vertex. An angle divides the plane into its interior (inside the arms) and exterior (outside the arms). We'll look closely at triangles (three-sided polygons) and quadrilaterals (four-sided polygons), identifying their sides, vertices, and angles.

Finally, we explore the perfectly round shape: the circle. A circle is a set of points in a plane that are all the same distance from a fixed central point. Key parts of a circle include:

- The center: The fixed point inside.

- The radius: The distance from the center to any point on the circle.

- The diameter: A line segment passing through the center with endpoints on the circle (it's twice the radius).

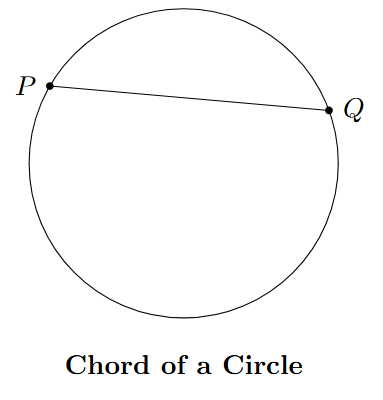

- A chord: Any line segment whose endpoints lie on the circle.

- An arc: A portion of the circle's boundary.

- A sector: A region inside the circle bounded by two radii and an arc (like a pizza slice).

- A segment: A region inside the circle bounded by a chord and an arc.

Point, Line and Plane

Geometry is a branch of mathematics that helps us understand the world around us by studying shapes, sizes, positions of figures, and properties of space. In this chapter, we will begin our journey into geometry by learning about its most basic building blocks: the point, the line, and the plane.

These fundamental concepts are idealised, meaning they exist in our mathematical thoughts but are represented by simple models in drawings.

Point

Imagine marking a position with a very sharp pencil tip on a paper. That mark represents a point. A point is a fundamental concept in geometry that describes a location in space. It has no size, no dimension (zero dimension), no length, no breadth, and no thickness. It simply indicates an exact position.

Points are usually represented by a tiny dot and are named using a capital letter for identification.

Examples of models of a point in real life include:

- The sharp tip of a pen or pencil.

- The corner of a table.

- The location of a city on a map.

- A star in the night sky (from our perspective).

Points help us to specify an exact location.

Line

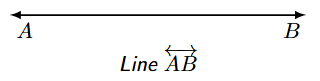

A line is defined as a straight, one-dimensional figure that has no thickness and extends infinitely in both opposite directions. It is a fundamental concept in geometry. A line is composed of a set of infinite points that are arranged in a straight path.

Graphically, we represent a line by drawing a straight path and placing arrowheads at both ends. These arrowheads signify that the line continues endlessly in both directions.

A line can be named in two common ways:

- By using a single lowercase letter, such as line $l$, line $m$, or line $n$.

- By picking any two distinct points on the line and using their capital letters. For example, if points A and B are on the line, we can call it line AB. The notation for this is $\overleftrightarrow{AB}$ or $\overleftrightarrow{BA}$.

Since a line is infinite in length, it is impossible to draw it completely on paper. We only draw a segment of it and use arrows to indicate its infinite nature.

Important Property: An essential axiom in Euclidean geometry states that through any two distinct given points, there is exactly one unique straight line that can be drawn.

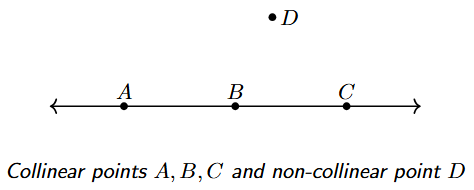

Collinear Points

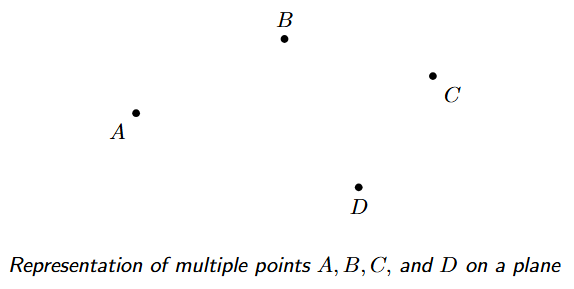

When three or more points lie on the same single straight line, they are said to be collinear points. Conversely, points that do not lie on the same straight line are called non-collinear points.

In the figure shown above, points A, B, and C are collinear as they all fall on the same straight line. Point D, however, is a non-collinear point with respect to A, B, and C because it does not lie on the same line.

Note that any two points are always collinear, as per the property mentioned above, that a unique straight line can always be drawn passing through them.

Plane

A plane is a fundamental concept in geometry representing a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely far in all directions. A plane has length and width but no thickness (depth). It can be thought of as the surface of a perfectly flat sheet of paper that goes on forever.

Even though a plane extends infinitely, for visualization purposes, it is often represented in diagrams by a four-sided figure like a parallelogram or a rectangle.

Examples of objects that model a part of a plane include:

- The surface of a smooth wall.

- The floor of a room.

- The top surface of a table.

- The surface of a still lake.

A plane consists of an infinite number of points and can contain an infinite number of lines.

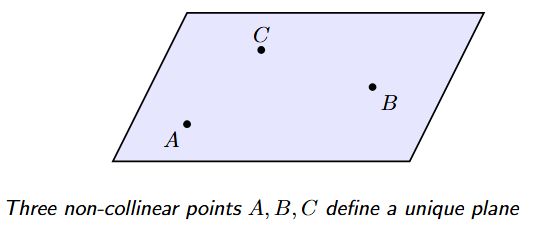

Important Property: Three non-collinear points (points that do not lie on the same straight line) are required to define a unique plane. This means that there is exactly one plane that can pass through any three given non-collinear points.

Intersecting and Parallel Lines

When we consider two lines in the same plane, they can either cross each other or never cross. This gives us the concepts of intersecting and parallel lines.

Intersecting Lines:

Two distinct lines in the same plane are called intersecting lines if they cross each other at exactly one common point. The point where they meet is called the point of intersection.

In the diagram above, Line $L_1$ and Line $L_2$ are intersecting lines, and P is their point of intersection.

Any two non-parallel lines in the same plane will always intersect at exactly one point.

Parallel Lines:

Two distinct lines in the same plane are called parallel lines if they never meet or intersect, no matter how far they are extended in either direction. The perpendicular distance between two parallel lines is always the same at all points.

In the diagram above, Line $L_1$ and Line $L_2$ are parallel lines. They will never intersect.

Examples of parallel lines in real life include:

- Opposite edges of a straight ruler or a book.

- Railway tracks (assuming they are perfectly straight and level).

- Parallel lines drawn in a notebook.

- Opposite sides of a rectangle or square.

Properties of Points, Lines, and Planes

The following are some of the fundamental properties and axioms that describe the relationships between points, lines, and planes in Euclidean geometry. Understanding these axioms is crucial for building a foundation in geometry.

1. An infinite number of lines can pass through a single point.

Imagine a single point in space. You can draw one line passing through it. Now, you can pivot or rotate this line around that fixed point. Each new angle of rotation creates a new, distinct line. Since there are infinite possible angles for rotation, an infinite number of unique lines can be drawn through that single point.

2. Exactly one unique line can pass through two distinct points.

This is a foundational axiom of geometry. If you have two different points, say Point A and Point B, there is only one possible straight path that connects them and extends infinitely in both directions. You cannot draw a second, different straight line that also passes through both A and B. Any other path connecting them would have to be curved, and thus would not be a line.

3. If two distinct lines intersect, they intersect at exactly one point.

By definition, a line is a straight path. If two different (distinct) straight lines were to cross at more than one point, they would have to curve to meet again, which contradicts the definition of a line. Therefore, two distinct straight lines can only share one common point. If they share two or more points, they must be the exact same line.

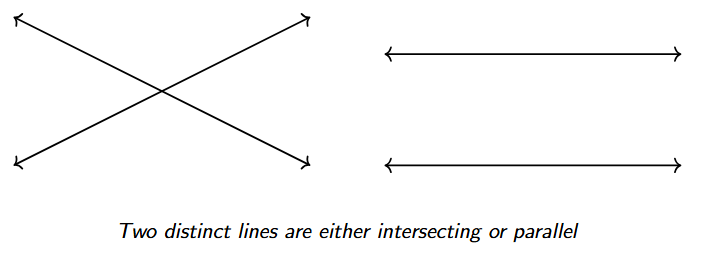

4. Two distinct lines in a plane are either intersecting or parallel.

This property outlines the only two possible relationships for two different lines on a flat surface (a plane).

- Intersecting: The lines cross each other at one single point.

- Parallel: The lines maintain a constant distance from each other and never cross, no matter how far they are extended.

There is no third possibility for two distinct straight lines within the same plane.

5. Three non-collinear points define a unique plane.

To define a single, specific flat surface (a plane), you need at least three points that are not all in a straight line. A three-legged stool is always stable because its three feet (points) define a single plane (the floor). If you only have two points, you can rotate a plane around the line connecting them, meaning infinite planes can pass through those two points. A third point, not on that line, fixes the plane in a unique position.

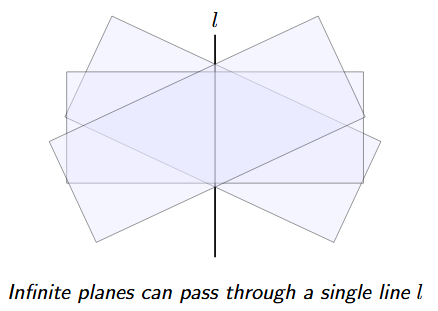

6. An infinite number of planes can pass through a single line.

Imagine a single line in space acting as the spine of an open book. Each page of the book represents a different plane. All of these planes pass through and share the same spine (the line). Since you can have an infinite number of "pages" at different angles around the spine, it follows that an infinite number of planes can pass through a single line.

7. If two points lie in a plane, the entire line containing them lies in that plane.

This property describes the inherent "flatness" of a plane. If you choose any two points on a flat surface and draw the unique straight line that passes through them, every single point on that line will also lie on that same flat surface. The line does not curve away or leave the plane at any point.

8. The intersection of two distinct, non-parallel planes is a line.

When two flat surfaces (planes) cross each other, the location where they meet forms a straight line. A common real-world example is the corner of a room where two walls meet; their intersection is a straight line running from the floor to the ceiling. Another example is the crease formed when a piece of paper is folded; this crease is the line of intersection between the two planes formed by the folded paper.

Line Segment, Ray, and Their Properties

In the previous section, we learned about a line as a straight path that extends infinitely in both directions. However, in practical geometry, we often work with specific parts of lines. Two fundamental parts of a line are the line segment and the ray. These are distinct from a line because they do not extend infinitely in both directions.

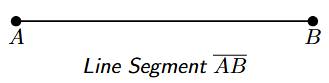

Line Segment

A line segment is a part of a line that is bounded by two distinct endpoints. It contains these endpoints and all the points on the line between them. The primary characteristic of a line segment is that it has a fixed, measurable length.

A line segment with endpoints A and B is denoted as $\overline{AB}$ or $\overline{BA}$. The order of the endpoints does not matter when naming a line segment. The length of the line segment $\overline{AB}$ is denoted simply as AB.

Examples of models representing line segments in real life include:

- The edge of a table or a book.

- A pencil or a ruler.

- A stretched piece of thread between two points.

Midpoint of a Line Segment

The midpoint of a line segment is the point that divides the segment into two equal, or congruent, line segments. If M is the midpoint of the line segment $\overline{AB}$, then the length of AM is equal to the length of MB.

We can express this relationship mathematically as:

$AM = MB = \frac{1}{2}AB$

A line segment has exactly one midpoint.

Congruent Line Segments

Two line segments are said to be congruent if they have the same length. The symbol for congruence is $\cong$. So, if line segment $\overline{AB}$ and line segment $\overline{CD}$ have the same length (i.e., AB = CD), then we can write:

$\overline{AB} \cong \overline{CD}$

Ray

A ray is also a part of a line. It has one fixed endpoint (called the initial point or origin) and extends infinitely in one direction from that point.

A ray is named using its endpoint first, followed by any other point on the ray. For example, a ray starting at endpoint A and passing through point B is denoted as $\overrightarrow{AB}$. The order of the letters is crucial:

- The first letter must be the endpoint.

- The second letter indicates the direction of the infinite extension.

Therefore, $\overrightarrow{AB}$ and $\overrightarrow{BA}$ are two different rays. $\overrightarrow{BA}$ would start at B and extend infinitely through A.

Since a ray extends infinitely in one direction, it does not have a measurable length.

Examples of models of rays in real life:

- A ray of light from the sun or a flashlight.

- The beam from a laser pointer.

Opposite Rays

Two rays are called opposite rays if they share the same endpoint and form a straight line. For three collinear points A, O, and B, if O is between A and B, then $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{OB}$ are opposite rays.

The union of two opposite rays is a line.

Comparing Line, Line Segment, and Ray

The following table summarizes the key differences between a line, a line segment, and a ray:

| Feature | Line | Line Segment | Ray |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoints | Zero endpoints | Two endpoints | One endpoint (initial point) |

| Extension | Extends infinitely in both directions | Does not extend; has a fixed position | Extends infinitely in one direction |

| Length | Infinite (cannot be measured) | Finite and definite (can be measured) | Infinite (cannot be measured) |

| Notation Symbol | $\overleftrightarrow{AB}$ | $\overline{AB}$ or $\overline{BA}$ | $\overrightarrow{AB}$ (starting point first) |

| Diagram |  |

|

|

Angle - Interior and Exterior

In geometry, when two rays or line segments meet at a common point, they form an angle. Angles are a fundamental concept used to describe the amount of turn or the shape of corners in figures.

Angle

An angle is a figure formed by two rays that share a common endpoint. This common endpoint is the corner point of the angle.

An angle consists of two main parts:

- Arms (or Sides): The two rays that form the angle are called its arms or sides. In the figure above, the rays $\overrightarrow{BA}$ and $\overrightarrow{BC}$ are the arms of the angle.

- Vertex: The common endpoint from which the two rays originate is called the vertex of the angle. In the figure, point B is the vertex.

Naming an Angle

It is important to name angles correctly to avoid confusion. There are three common methods:

- Using Three Letters: This is the most precise method. The angle is named using three points: one point on each arm and the vertex in the middle. For the angle shown above, we can name it $\angle ABC$ or $\angle CBA$. The vertex letter must always be the middle letter.

- Using the Vertex Letter: If there is only one angle associated with a vertex, you can name the angle using just the single capital letter of the vertex. For the angle above, we could call it $\angle B$. However, this method can be ambiguous if multiple angles share the same vertex, as shown below.

- Using a Number or Symbol: Sometimes, especially in complex diagrams, a small number or a symbol (like $x$ or $\theta$) is placed inside the angle near the vertex. The angle is then referred to by that number or symbol, such as $\angle 1$ or $\angle x$.

In the right-side diagram, calling the angle "$\angle P$" would be unclear. Does it refer to $\angle APB$, $\angle BPC$, or $\angle APC$? In such cases, the three-letter method is necessary.

Magnitude of an Angle

The "size" of an angle is a measure of the amount of rotation or opening between its two arms. This measure is typically expressed in units called degrees ($^\circ$). A full circle of rotation is divided into 360 degrees.

- A full turn is $360^\circ$.

- A straight line forms an angle of $180^\circ$.

- A right angle (like the corner of a square) is $90^\circ$.

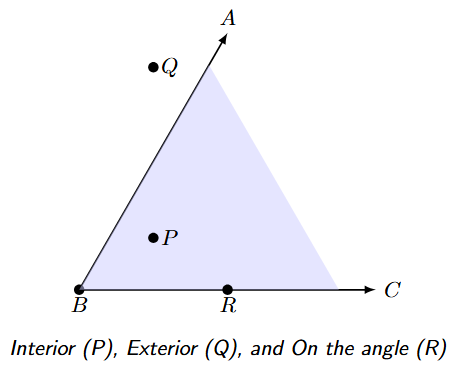

Interior and Exterior of an Angle

Any angle drawn on a plane divides all the points of the plane into three distinct regions:

1. The Interior of the Angle

The interior of an angle is the set of all points that lie "inside" the two arms of the angle. It is the region of the plane that is between the two rays. In the diagram above, the shaded region represents the interior of $\angle ABC$, and point P lies in the interior.

2. The Exterior of the Angle

The exterior of an angle is the set of all points in the plane that are not in the interior and are not on the angle itself. It is the entire region "outside" the arms of the angle. In the diagram, point Q lies in the exterior of $\angle ABC$.

3. On the Angle

A point is said to be on the angle if it lies on either of the two rays (arms) that form the angle. The vertex is also a point on the angle. In the diagram, point B (the vertex) and point R are on the angle $\angle ABC$.

Curves: Open, Closed, and Simple

In everyday language, a "curve" refers to something that is bent and not straight. However, in mathematics, the term has a broader meaning. A curve can be thought of as any path drawn on a plane without lifting the drawing tool. This means even a perfectly straight line is considered a type of curve in geometry.

Defining a Curve

A curve is a continuous line or shape drawn on a surface without lifting the pencil. Curves can be straight, bent, or a combination of both.

Simple vs. Non-Simple Curves

A key distinction among curves is whether they cross over themselves.

- A Simple Curve is a curve that does not cross itself at any point.

- A Non-Simple Curve (or Complex Curve) is a curve that crosses itself at one or more points.

Now, let's combine this idea with whether the curve is open or closed.

Open Curve

An open curve is a curve whose starting and ending points are different. It does not enclose any area and has two distinct endpoints.

Examples of open curves include:

- A line segment or a ray.

- A parabola or a hyperbola.

- The shapes of letters like 'C', 'S', 'U', or 'M'.

Closed Curve

A closed curve is a curve whose starting and ending points are the same. It forms a complete loop and encloses a region of the plane.

Examples of closed curves include:

- A circle, an ellipse, or an oval.

- Polygons like triangles, squares, and pentagons.

- The shapes of letters like 'O', 'D', or 'P'.

Simple Closed Curve

A simple closed curve is a curve that is both simple (it does not cross itself) and closed (its start and end points are the same). These are the most common shapes we study in basic geometry, such as polygons and circles.

- Simple Closed Curve: A circle, a square, or a triangle. They are closed and do not intersect themselves.

- Non-Simple Closed Curve: The figure '8' or a five-pointed star drawn without lifting the pen. They are closed, but they cross over themselves.

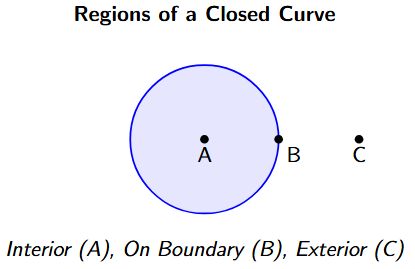

Regions of a Simple Closed Curve

A fundamental property of any simple closed curve (like a circle or a polygon) is that it divides the plane into three distinct and separate parts. This concept is part of the Jordan Curve Theorem.

The three regions are:

- The Interior ('Inside'): This is the finite region that is completely enclosed by the curve. In the diagram, Point A is in the interior.

- The Boundary ('On'): This is the curve itself. It acts as the "fence" that separates the inside from the outside. In the diagram, Point B is on the boundary.

- The Exterior ('Outside'): This is the infinite region of the plane that is outside the curve. In the diagram, Point C is in the exterior.

Every point on the plane must belong to exactly one of these three regions. You cannot get from the interior to the exterior without crossing the boundary.

Polygons and Their Classification

Having explored basic geometric figures, we now focus on a specific and very important type of simple closed curve known as a polygon. Polygons are fundamental shapes that form the basis of many objects and structures we see in the world, from the triangular shape of a roof truss to the hexagonal cells of a honeycomb.

The word "polygon" originates from the Greek words poly (meaning "many") and gon (meaning "angle"). Thus, a polygon is literally a "many-angled" figure.

Definition of a Polygon

A polygon is a two-dimensional shape defined as a simple closed curve made up entirely of straight line segments. Let's break down this definition:

- Simple: The line segments do not cross over each other.

- Closed: The line segments form a complete path, with the starting point being the same as the ending point, enclosing a region.

- Made of Line Segments: The boundary of the shape consists only of straight lines; there are no curves.

Based on the definition:

- Figures (a), (b), and (c) are polygons.

- Figure (d) is not a polygon because it is an open curve.

- Figure (e) is not a polygon because it is not made of line segments.

- Figure (f) is not a polygon because it is not a simple curve (it intersects itself).

Parts of a Polygon

Every polygon has specific named parts. Let's use a pentagon ABCDE to illustrate them.

- Sides: The line segments that form the boundary of the polygon are its sides. The pentagon ABCDE has 5 sides: $\overline{AB}, \overline{BC}, \overline{CD}, \overline{DE},$ and $\overline{EA}$.

- Vertices: A vertex is a point where two sides meet (a corner). The pentagon has 5 vertices: A, B, C, D, and E. The number of vertices is always equal to the number of sides.

- Adjacent Sides: Any two sides that share a common vertex are adjacent sides. For example, $\overline{AB}$ and $\overline{BC}$ are adjacent because they meet at vertex B.

- Adjacent Vertices: The two endpoints of any single side are adjacent vertices. For example, vertices A and B are adjacent as they are the endpoints of side $\overline{AB}$.

- Diagonals: A diagonal is a line segment that connects two non-adjacent vertices. In the pentagon, $\overline{AC}$ is a diagonal because vertices A and C are not adjacent. The number of diagonals in an n-sided polygon is given by the formula $\frac{n(n-3)}{2}$.

Classification of Polygons

Polygons can be classified in several ways, most commonly by the number of their sides, their shape, and the equality of their sides and angles.

1. Classification by Number of Sides

The name of a polygon is determined by its number of sides. A polygon must have at least 3 sides.

| Number of Sides | Name of Polygon | Example Figure |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Triangle |  |

| 4 | Quadrilateral |  |

| 5 | Pentagon |  |

| 6 | Hexagon |  |

| 7 | Heptagon |  |

| 8 | Octagon |  |

| 9 | Nonagon |  |

| 10 | Decagon |  |

For polygons with more sides, we often use the general term 'n-gon' (e.g., a 17-sided polygon is a 17-gon).

2. Convex and Concave Polygons

- Convex Polygon: A polygon is convex if all its interior angles are less than $180^\circ$. All vertices seem to point "outwards". Any diagonal drawn on a convex polygon lies entirely inside the polygon.

- Concave Polygon: A polygon is concave if it has at least one interior angle greater than $180^\circ$ (a reflex angle). This creates a "dent" or a "cave" in the shape. At least one diagonal of a concave polygon will lie partially or wholly outside the polygon.

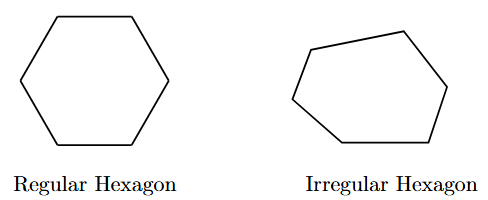

3. Regular and Irregular Polygons

- Regular Polygon: A polygon is regular if it is both equilateral (all sides are equal in length) and equiangular (all interior angles are equal in measure). Examples include the equilateral triangle, the square, and the regular pentagon.

- Irregular Polygon: A polygon that is not regular is an irregular polygon. It might have equal sides but unequal angles (like a rhombus) or equal angles but unequal sides (like a rectangle).

In-depth Look at Key Polygons

Triangles (3-sided polygon)

A triangle is a polygon with three sides, three vertices, and three interior angles. The sum of its interior angles is always $180^\circ$.

Classification of Triangles by Sides:

- Equilateral Triangle: All three sides are of equal length. All three angles are equal ($60^\circ$ each). It is a regular polygon.

- Isosceles Triangle: Two sides are of equal length. The angles opposite these equal sides are also equal.

- Scalene Triangle: All three sides have different lengths, and all three angles have different measures.

Classification of Triangles by Angles:

- Acute Triangle: All three interior angles are acute (less than $90^\circ$).

- Right Triangle: One interior angle is a right angle (exactly $90^\circ$). The side opposite the right angle is the hypotenuse.

- Obtuse Triangle: One interior angle is obtuse (greater than $90^\circ$).

Components of a Triangle

Sides, Vertices, and Angles: As defined above, a triangle has three sides (line segments), three vertices (corners), and three interior angles.

Altitude: An altitude of a triangle is the perpendicular line segment from a vertex to the opposite side. It represents the 'height' of the triangle from that vertex. A triangle has three altitudes, which meet at the orthocenter.

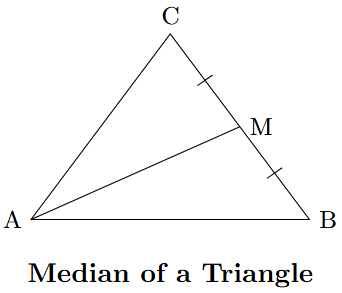

Median: A median of a triangle is a line segment that connects a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. A triangle has three medians, which meet at the centroid.

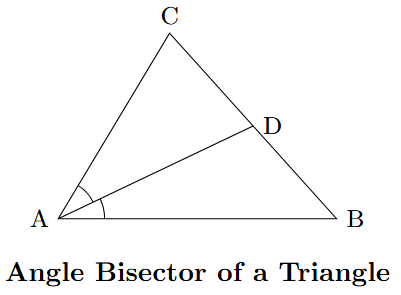

Angle Bisector: An angle bisector is a line segment that divides an interior angle of the triangle into two equal angles. A triangle has three angle bisectors, which meet at the incenter.

Quadrilaterals (4-sided polygon)

A quadrilateral is a polygon with four sides, four vertices, and four interior angles. The sum of the measures of its interior angles is always $360^\circ$.

Types of Quadrilaterals

- Trapezium (or Trapezoid): A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides.

- Parallelogram: A quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides.

- Rectangle: A parallelogram with four right angles.

- Rhombus: A parallelogram with four equal sides.

- Square: A parallelogram that is both a rectangle and a rhombus (four right angles and four equal sides).

- Kite: A quadrilateral with two distinct pairs of equal-length adjacent sides.

Components of a Quadrilateral

Adjacent and Opposite Sides: Adjacent sides share a common vertex (e.g., $\overline{AB}$ and $\overline{BC}$). Opposite sides do not share a vertex (e.g., $\overline{AB}$ and $\overline{DC}$).

Adjacent and Opposite Angles: Adjacent angles share a common side (e.g., $\angle A$ and $\angle B$). Opposite angles do not share a side (e.g., $\angle A$ and $\angle C$).

Diagonals: A diagonal is a line segment that connects two opposite (non-adjacent) vertices. A quadrilateral has two diagonals ($\overline{AC}$ and $\overline{BD}$).

Circle and Terms Associated With a Circle

In our study of geometry, we've focused on polygons, which are made of straight line segments. We now turn our attention to another fundamental simple closed curve: the circle. A circle is a perfectly round shape, distinguished by its lack of straight sides and corners. It is one of the most common and important shapes in mathematics and nature, appearing in objects like wheels, coins, and the orbits of planets.

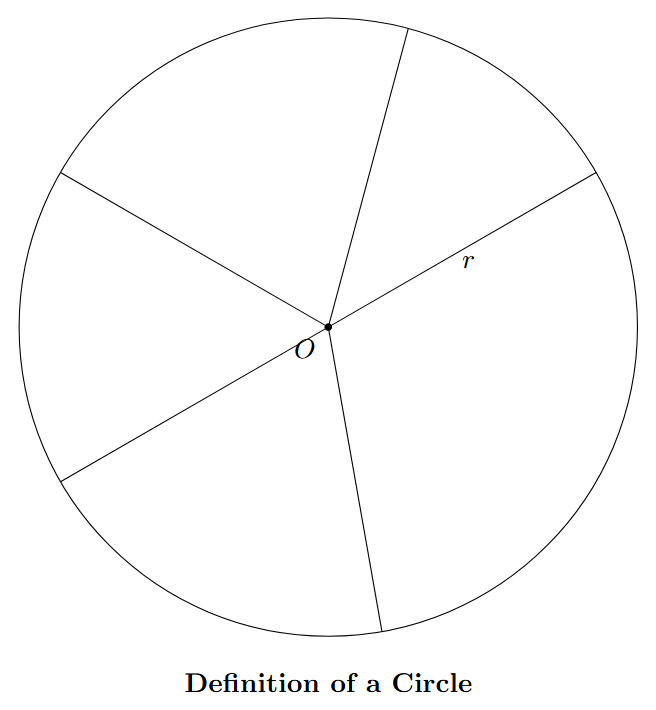

Definition of a Circle

A circle is formally defined as the set (or collection) of all points in a plane that are at a constant, fixed distance from a single fixed point in the same plane.

- The fixed point is called the centre of the circle (Point O in the figure).

- The fixed distance from the centre to any point on the circle is called the radius of the circle (labeled as 'r').

In simple terms, if you fix a point (the centre) and then draw all the points that are exactly the same distance away from it, you will form a circle.

Regions of a Circle

A circle, like any simple closed curve, divides the plane it occupies into three distinct regions:

- Interior of the Circle: This is the region consisting of all points inside the boundary of the circle. A point P is in the interior if its distance from the centre O is less than the radius ($OP < r$).

- Exterior of the Circle: This is the region consisting of all points outside the boundary of the circle. A point Q is in the exterior if its distance from the centre O is greater than the radius ($OQ > r$).

- On the Circle (Boundary): This refers to the set of points that make up the circle itself. A point R is on the circle if its distance from the centre O is exactly equal to the radius ($OR = r$).

The length of the boundary of a circle is given a special name: the circumference.

Terms Associated With a Circle

To discuss circles effectively, we use a specific vocabulary. The following terms are essential.

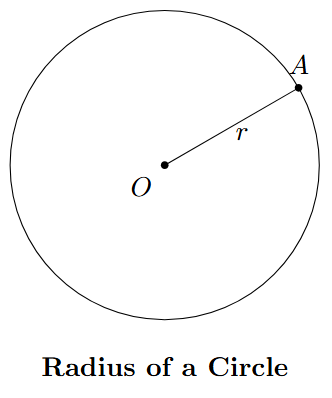

Radius

A radius is any line segment that connects the centre of the circle to a point on its boundary. The term "radius" can refer to this line segment or its length. All radii of a given circle are equal in length. (Plural: radii).

Chord

A chord is a line segment whose two endpoints lie on the boundary of the circle. It connects any two points on the circle.

Diameter

A diameter is a special type of chord that passes through the centre of the circle. It is the longest possible chord in a circle. The length of the diameter is always twice the length of the radius.

$\text{Diameter} = 2 \times \text{Radius}$

$D = 2r$

... (i)

Arc

An arc is a continuous portion of the circumference (boundary) of a circle between two points. A chord, like $\overline{AB}$, divides the circumference into two arcs:

- Minor Arc: The shorter arc between the two points (shown in red). It is denoted as $\overset{\frown}{AB}$.

- Major Arc: The longer arc between the two points (shown in blue). It is often denoted using a third point, like $\overset{\frown}{ACB}$, to distinguish it from the minor arc.

- Semicircle: If the two points are the endpoints of a diameter, the arc is a semicircle, which is exactly half of the circumference.

Segment

A segment of a circle is the region in the interior enclosed by a chord and its corresponding arc. A chord divides the circle's interior into two segments:

- Minor Segment: The smaller region enclosed by the chord and the minor arc.

- Major Segment: The larger region enclosed by the chord and the major arc.

Sector

A sector of a circle is the region in the interior enclosed by two radii and the arc between their endpoints. It resembles a slice of a pie. Two radii divide the circle's interior into two sectors:

- Minor Sector: The smaller "slice" enclosed by the two radii and the minor arc.

- Major Sector: The larger "slice" enclosed by the two radii and the major arc.

Circumference

The circumference is the total length of the boundary of the circle. It is the perimeter of the circle. The formula for the circumference C is $C = 2\pi r$, where $r$ is the radius and $\pi$ (pi) is a mathematical constant approximately equal to 3.14159.

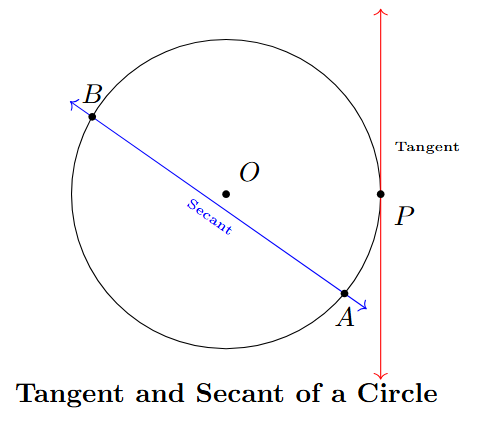

Tangent and Secant

- Secant: A secant is a line that intersects a circle at two distinct points. It can be thought of as a chord that is extended infinitely in both directions.

- Tangent: A tangent is a line that touches the circle at exactly one point, called the point of tangency.