| Classwise Concept with Examples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th |

| Content On This Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Construction of Quadrilaterals | Construction of Parallelograms | Construction of Rectangles, Rhombi and Squares |

Chapter 4 Practical Geometry (Concepts)

Building directly upon the foundational construction skills acquired in Class 7, where the focus was primarily on triangles, this chapter on Practical Geometry elevates our expertise to the realm of quadrilaterals. Here, we transition from the inherent rigidity of three-sided figures to the more flexible nature of four-sided polygons. The central objective is to master the accurate construction of various types of quadrilaterals using the fundamental tools of geometry: an unmarked ruler (straightedge) and a pair of compasses, occasionally supplemented by a protractor for specific angle requirements.

A critical prerequisite for success in this chapter is a solid understanding of the diverse properties of quadrilaterals – concepts thoroughly explored in the preceding theoretical chapter. Unlike triangles, where three specific measurements (like SSS or SAS) are generally sufficient to define a unique shape due to their inherent structural stability, quadrilaterals are not inherently rigid. Simply knowing the lengths of four sides, for instance, does not guarantee a unique quadrilateral; imagine a square frame that can be easily deformed into a rhombus. Therefore, constructing a specific, unique quadrilateral requires more information. This chapter systematically explores scenarios where exactly five specific measurements are provided, establishing the conditions needed to lock down the shape and size uniquely.

We will meticulously learn the step-by-step procedures for constructing quadrilaterals under various given conditions. The typical scenarios encountered include:

- Constructing a quadrilateral given the lengths of its four sides and one diagonal. This method cleverly relies on breaking the quadrilateral into two triangles using the given diagonal and then applying the SSS triangle construction criterion twice.

- Constructing a quadrilateral when the lengths of three sides and both diagonals are known.

- Constructing a quadrilateral given the lengths of two adjacent sides and the measures of three angles.

- Constructing a quadrilateral when provided with the lengths of three sides and the measures of the two included angles (the angles between the pairs of known sides).

- Constructing special quadrilaterals based on minimal information derived from their unique properties, such as constructing a square given only the length of one side, or constructing a rhombus given the lengths of its diagonals.

Each construction follows a disciplined, logical process, essential for achieving accuracy:

- Draw a Rough Sketch: Always begin by sketching a freehand representation of the quadrilateral, labeling it with the given measurements. This crucial first step helps visualize the final figure, plan the sequence of construction steps, and anticipate potential issues.

- Execute Precise Construction: Using the ruler, draw initial line segments to the specified lengths. Employ the compasses meticulously to draw arcs representing side lengths or distances from specific points. Use a protractor, or where applicable, compass-and-ruler techniques (for constructible angles like $60^\circ$, $90^\circ$, $120^\circ$), to set out the required angles accurately.

- Locate Vertices: The precise points where lines intersect or arcs intersect lines/other arcs determine the exact locations of the quadrilateral's vertices.

This chapter strongly emphasizes precision in measurement and drawing, alongside the logical sequencing of steps rooted in geometric principles. It reinforces the understanding that specific combinations of five measurements (sides, angles, diagonals) are generally necessary and sufficient to uniquely define a quadrilateral. Implicitly, we also consider the conditions under which a construction is possible – for example, the lengths involved must satisfy the Triangle Inequality Property for any triangles formed within the quadrilateral during construction. Ultimately, mastering these techniques significantly enhances spatial reasoning, geometric intuition, and practical technical drawing skills.

Construction of Quadrilaterals

Practical geometry is all about constructing geometric shapes with given measurements using tools like a ruler (straightedge), compasses, protractor, and pencil. You have already learned how to construct triangles uniquely when given specific sets of three measurements (SSS, SAS, ASA, RHS). A triangle is the simplest polygon.

Now, we extend our construction skills to quadrilaterals, which are polygons with four sides. A quadrilateral is a more complex figure, having four sides, four angles, and two diagonals – a total of ten parts. To construct a quadrilateral uniquely, we need to know the lengths of its sides, the measures of its angles, or the lengths of its diagonals in specific combinations.

Requirements for Constructing a Unique Quadrilateral

Unlike a triangle which needs 3 measurements, a quadrilateral generally requires five independent measurements for a unique construction. These measurements must be given in a way that fixes the position of all four vertices.

Let's explore the different sets of five measurements that are sufficient to construct a unique convex quadrilateral.

Different Cases for Constructing a Quadrilateral

A convex quadrilateral can be constructed uniquely using a ruler, compasses, and protractor under the following conditions:

Case 1: When the lengths of four sides and one diagonal are given.

This is one of the most common cases. A diagonal divides a quadrilateral into two triangles. If you know the lengths of all four sides and the length of one diagonal, you can construct each of the two triangles separately using the SSS (Side-Side-Side) construction criterion, since all three sides of each triangle are known. Then, you join the two triangles along the common diagonal.

Example 1. Construct a quadrilateral ABCD where AB = 4 cm, BC = 5 cm, CD = 6 cm, AD = 5.5 cm, and diagonal AC = 7 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of side AB = 4 cm | Length of side BC = 5 cm |

| Length of side CD = 6 cm | Length of side AD = 5.5 cm |

| Length of diagonal AC = 7 cm |

To Construct:

A quadrilateral ABCD.

Construction Steps:

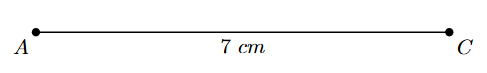

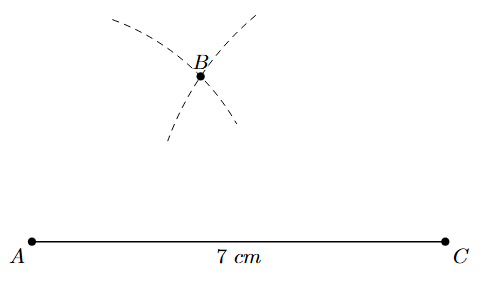

1. Start by drawing the given diagonal AC. Draw a line segment AC of length 7 cm.

2. Now, we will locate vertex B. Vertex B is 4 cm away from A and 5 cm away from C. With A as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of AB (4 cm) above the segment AC. With C as the centre, draw another arc with a radius equal to the length of BC (5 cm) above the segment AC. The point where these two arcs intersect is the vertex B.

3. Join the points A to B and C to B with line segments. You have now constructed $\triangle$ABC.

4. Next, we will locate vertex D, which is on the opposite side of diagonal AC from B. Vertex D is 5.5 cm away from A and 6 cm away from C. With A as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of AD (5.5 cm) below the segment AC. With C as the centre, draw another arc with a radius equal to the length of CD (6 cm) below the segment AC. The point where these two arcs intersect is the vertex D.

5. Join the points A to D and C to D with line segments. You have now constructed $\triangle$ADC.

6. Join the vertices in order (A to B, B to C, C to D, and D to A) to form the quadrilateral ABCD. The figure ABCD is the required quadrilateral.

Justification:

By constructing $\triangle$ABC with sides AB=4cm, BC=5cm, and AC=7cm, we uniquely determine the positions of A, B, and C. Similarly, by constructing $\triangle$ADC with sides AD=5.5cm, CD=6cm, and AC=7cm on the opposite side of AC, we uniquely determine the position of D relative to A and C. Since the base AC is common and its length is fixed, combining these two uniquely determined triangles forms a unique quadrilateral ABCD with the given side lengths and diagonal length.

Case 2: When the lengths of three sides and two diagonals are given.

In this scenario, the given measurements allow us to construct one of the triangles formed within the quadrilateral (either one side and two diagonals, or two sides and one diagonal) using the SSS criterion. Once a triangle is fixed, the remaining measurements are used to locate the fourth vertex.

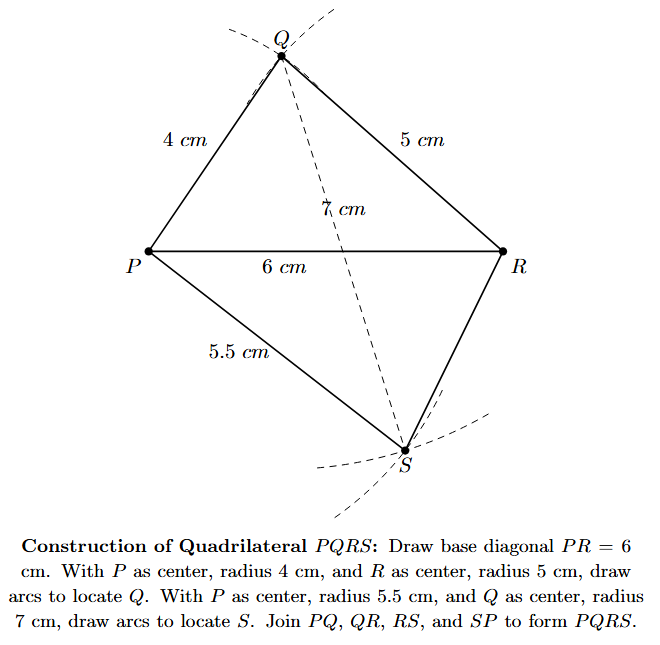

Example 2. Construct a quadrilateral PQRS where PQ = 4 cm, QR = 5 cm, PS = 5.5 cm, diagonal PR = 6 cm, and diagonal QS = 7 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of side PQ = 4 cm | Length of side QR = 5 cm |

| Length of side PS = 5.5 cm | Length of diagonal PR = 6 cm |

| Length of diagonal QS = 7 cm |

Construction Required:

A quadrilateral PQRS.

Construction Steps:

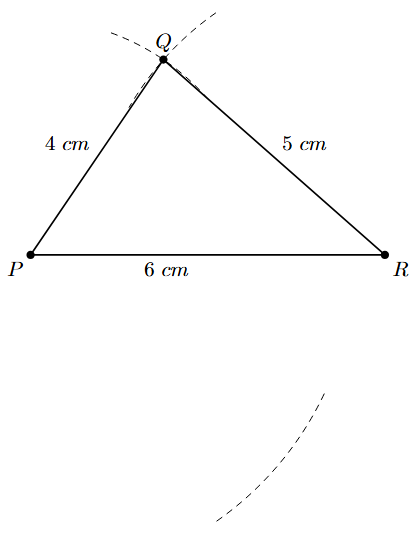

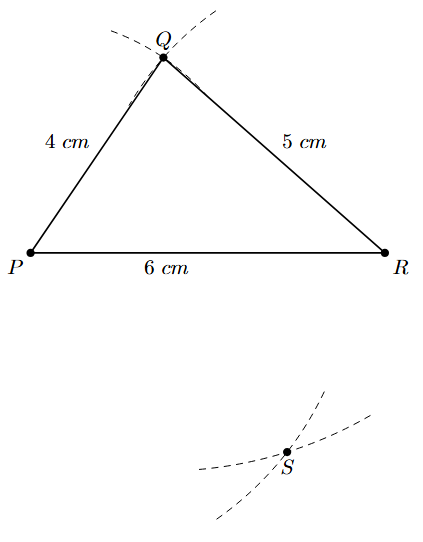

1. Observe the given measurements. We have sides PQ and QR and diagonal PR. These three lengths form triangle PQR (sides 4 cm, 5 cm, and 6 cm). Let's construct $\triangle$PQR first. Draw a line segment PR of length 6 cm (one of the given diagonals).

2. To locate vertex Q, which is 4 cm from P and 5 cm from R, use compasses. With P as centre, draw an arc with radius equal to the length of PQ (4 cm) on one side of PR. With R as centre, draw another arc with a radius equal to the length of QR (5 cm) on the same side of PR. The intersection of these two arcs is point Q.

3. Join the points P to Q and R to Q with line segments. You have constructed $\triangle$PQR.

4. Now, we need to locate the fourth vertex S. We know the length of side PS (5.5 cm) and the length of diagonal QS (7 cm). With P as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of PS (5.5 cm) on the side of PR opposite to Q.

5. With Q as the centre (Q is already located), draw another arc with a radius equal to the length of QS (7 cm). The intersection of the arc from P (step 4) and this arc from Q is point S.

6. Join the points P to S and R to S. Join Q to S (this is the second diagonal QS). The figure PQRS formed by joining the vertices in order is the required quadrilateral.

Justification:

Triangle PQR is uniquely constructed by SSS criterion. Points P, Q, R are fixed. Point S is uniquely determined as the intersection of two arcs: one centered at P with radius PS, and another centered at Q with radius QS. Since P and Q are fixed points and PS and QS are given lengths, the position of S is uniquely fixed. Thus, the quadrilateral PQRS with the given measurements is uniquely constructed.

Case 3: When two adjacent sides and three angles are given.

In this case, we are given the lengths of two sides that meet at a vertex, and three interior angles. The two given sides and the angle between them form two sides and the included angle of the quadrilateral. The other two given angles help in determining the directions of the remaining sides, leading to the location of the fourth vertex.

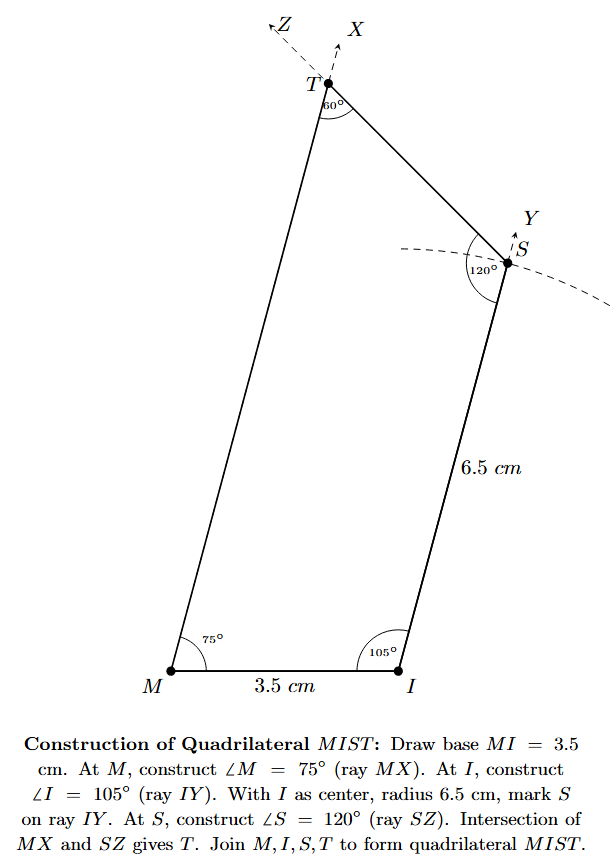

Example 3. Construct a quadrilateral MIST where MI = 3.5 cm, IS = 6.5 cm, $\angle$M = $75^\circ$, $\angle$I = $105^\circ$, and $\angle$S = $120^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of side MI = 3.5 cm | Length of side IS = 6.5 cm |

| Measure of $\angle$M = $75^\circ$ | Measure of $\angle$I = $105^\circ$ |

| Measure of $\angle$S = $120^\circ$ |

Construction Required:

A quadrilateral MIST.

Construction Steps:

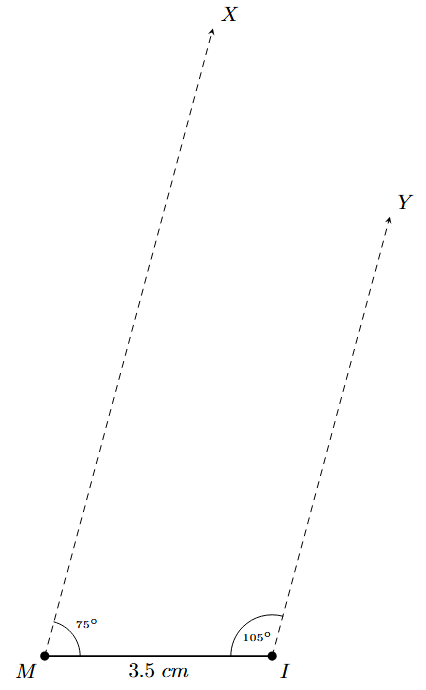

1. Draw a line segment MI of length 3.5 cm.

2. At point M, construct an angle equal to $\angle$M ($75^\circ$) using a protractor or compass. Draw a ray MX from M.

3. At point I, construct an angle equal to $\angle$I ($105^\circ$) using a protractor or compass. Draw a ray IY from I.

4. The side IS is 6.5 cm. With I as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of IS (6.5 cm) on the ray IY. The point where the arc intersects ray IY is the vertex S.

5. At point S (which is now located), construct an angle equal to $\angle$S ($120^\circ$) using a protractor. Draw a ray SZ from S.

6. The ray SZ will intersect the ray MX (drawn from M in step 2) at a point. This intersection point is the fourth vertex T.

7. MIST is the required quadrilateral.

Justification:

Side MI and angles at M and I are constructed as given, uniquely fixing the directions of rays MX and IY. Point S is uniquely located on ray IY at the given distance IS from I. Angle $\angle$ISZ is constructed as given, fixing the direction of ray SZ. The intersection of ray MX and ray SZ gives the unique position of point T. Thus, the quadrilateral MIST is uniquely determined by the given measurements.

Note: We could have first found the measure of the fourth angle $\angle$T using the angle sum property of a quadrilateral: $\angle$M + $\angle$I + $\angle$S + $\angle$T = $360^\circ$. So, $75^\circ + 105^\circ + 120^\circ + \angle$T = $360^\circ$, which gives $300^\circ + \angle$T = $360^\circ$, and $\angle$T = $60^\circ$. This knowledge might help in planning the construction or as a way to check the final angle, but it wasn't strictly necessary in this construction sequence.

Case 4: When Three Sides and Two Included Angles are given.

In this case, we are given the lengths of three consecutive sides and the measures of the two angles that are between these three sides. For example, if sides AB, BC, and CD are given, the included angles must be $\angle$B (between AB and BC) and $\angle$C (between BC and CD).

We start the construction by drawing the middle side among the three given sides (the one included between the two given angles). Then, we construct the two given angles at the endpoints of this middle side and mark the lengths of the other two given sides along the arms of these angles. Finally, we join the endpoints of these segments to complete the quadrilateral.

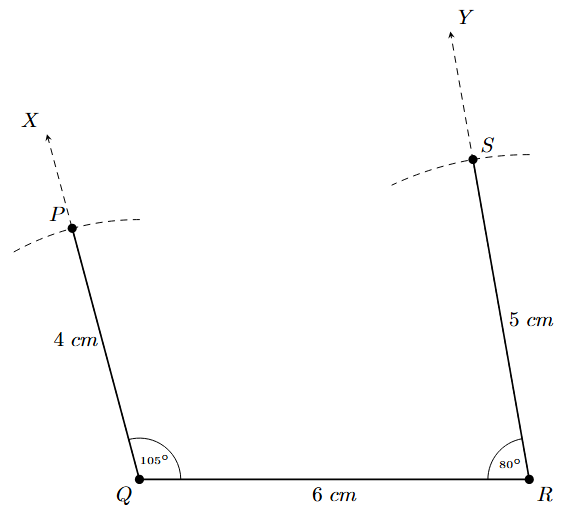

Example 4. Construct a quadrilateral PQRS where PQ = 4 cm, QR = 6 cm, RS = 5 cm, ∠Q = 105°, and ∠R = 80°.

Answer:

Given:

For quadrilateral PQRS:

- Three consecutive sides: PQ = 4 cm, QR = 6 cm, and RS = 5 cm.

- Two included angles: ∠Q = 105° and ∠R = 80°.

To Construct:

A quadrilateral PQRS with the given dimensions.

Steps of Construction:

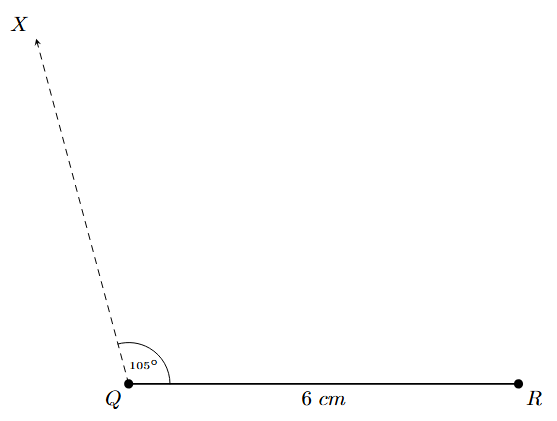

Step 1: Draw a line segment QR of length 6 cm. This will be the base for our construction.

Step 2: At point Q, use a protractor to construct an angle of 105°. Draw a ray QX from Q, such that ∠RQX = 105°.

Step 3: The vertex P lies on the ray QX and is 4 cm away from Q. With Q as the center and a radius of 4 cm, draw an arc that intersects the ray QX. Mark the intersection point as P.

Step 4: Now, at point R, use a protractor to construct an angle of 80°. Draw a ray RY from R on the same side as P, such that ∠QRY = 80°.

Step 5: The vertex S lies on the ray RY and is 5 cm away from R. With R as the center and a radius of 5 cm, draw an arc that intersects the ray RY. Mark the intersection point as S.

Step 6: Join the points P and S with a line segment using a ruler. This forms the fourth side of the quadrilateral.

The figure PQRS is the required quadrilateral.

Justification:

The construction is justified because the positions of all four vertices are uniquely determined. We start with a fixed base QR. The location of vertex P is uniquely fixed by the SAS condition (Side QR, Angle Q, Side QP). Similarly, the location of vertex S is uniquely fixed by the SAS condition (Side QR, Angle R, Side RS). Since the vertices P and S are unique points, the line segment joining them, PS, is also unique. Therefore, the quadrilateral PQRS is uniquely constructed.

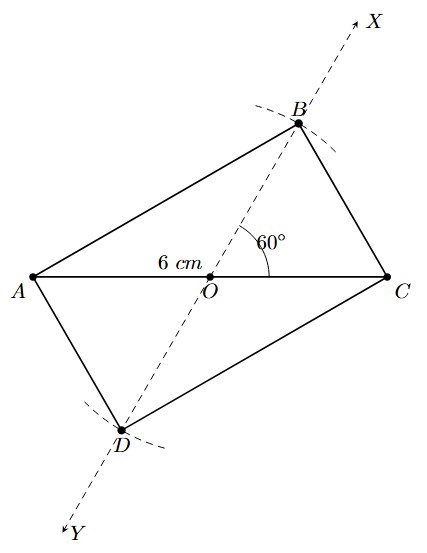

Construction of Parallelograms

Parallelograms are special types of quadrilaterals with specific properties that simplify their construction. Because opposite sides are parallel and equal, opposite angles are equal, adjacent angles are supplementary, and diagonals bisect each other, we don't need all five general measurements required for any quadrilateral. Knowing fewer measurements, if they are related in a specific way according to the properties of a parallelogram, is sufficient for unique construction.

We will look at some common cases for constructing a parallelogram.

Case 1: When the lengths of two adjacent sides and one angle are given.

In a parallelogram, if you know the lengths of two adjacent sides and the measure of the angle included between them, you can construct the entire parallelogram. This is similar to the SAS criterion for triangles.

Let the adjacent sides be $a$ and $b$, and the included angle be $\theta$. We can construct this angle at one vertex, mark the lengths $a$ and $b$ along the arms of the angle, and then use the property of opposite sides being equal to locate the fourth vertex.

Example 1. Construct a parallelogram ABCD where AB = 6 cm, BC = 4 cm, and $\angle$A = $60^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of adjacent side AB = 6 cm | Length of adjacent side BC = 4 cm |

| Measure of included angle $\angle$A = $60^\circ$ |

To Construct:

A parallelogram ABCD.

Construction Steps:

1. Draw a line segment AB of length 6 cm.

2. At point A, which is one endpoint of AB, construct an angle equal to $\angle$A ($60^\circ$) using a protractor or compass. Draw a ray AX originating from A.

3. The adjacent side AD has the same length as BC (opposite sides of a parallelogram are equal), which is 4 cm. With A as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of AD (4 cm) on the ray AX. The point where the arc intersects ray AX is the vertex D.

4. Now, we need to locate the fourth vertex C. We know that BC has length 4 cm and DC has the same length as AB (opposite sides are equal), which is 6 cm. With B as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of BC (4 cm).

5. With D as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of DC (6 cm). The intersection point of the arc from B (step 4) and this arc from D is the vertex C. Join the points B to C and D to C with line segments.

6. ABCD is the required parallelogram.

Justification:

By construction, AB = 6 cm, AD = 4 cm, and $\angle$A = $60^\circ$. Also, BC = 4 cm and DC = 6 cm. Since opposite sides AB=DC and AD=BC are equal in length, the quadrilateral ABCD is a parallelogram by definition (a quadrilateral with opposite sides equal is a parallelogram). The angle at A is $60^\circ$ as constructed. The construction uniquely determines the positions of all four vertices, resulting in a unique parallelogram.

Case 2: When the lengths of two adjacent sides and one diagonal are given.

Knowing the lengths of two adjacent sides and the length of one of the diagonals is also sufficient to construct a unique parallelogram. The diagonal divides the parallelogram into two triangles. Since opposite sides of a parallelogram are equal, you will have the lengths of all three sides of one of these triangles (two adjacent sides and the diagonal). You can construct this triangle using the SSS criterion and then use the property of opposite sides being equal to locate the fourth vertex.

Example 2. Construct a parallelogram PQRS where PQ = 5 cm, PS = 4 cm, and diagonal PR = 7 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of side PQ = 5 cm | Length of side PS = 4 cm |

| Length of diagonal PR = 7 cm |

To Construct:

A parallelogram PQRS.

Construction Steps:

1. Identify a triangle within the parallelogram that can be constructed using the given information. Triangle PQR has sides PQ and QR and diagonal PR. We know PQ = 5 cm, PR = 7 cm. In a parallelogram, opposite sides are equal, so QR = PS = 4 cm. Thus, we have the lengths of all three sides of $\triangle$PQR (5 cm, 4 cm, 7 cm). Let's construct $\triangle$PQR first. Draw the diagonal PR of length 7 cm.

2. To locate vertex Q, which is 5 cm from P and 4 cm from R, use compasses. With P as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of PQ (5 cm) on one side of PR. With R as the centre, draw another arc with a radius equal to the length of QR (4 cm) on the same side of PR. The intersection of these two arcs is point Q.

3. Join the points P to Q and R to Q with line segments. You have constructed $\triangle$PQR.

4. Now, we need to locate the fourth vertex S. We know the length of side PS (4 cm) and that side RS has the same length as PQ (opposite sides of a parallelogram are equal), which is 5 cm. With P as the centre, draw an arc with a radius equal to the length of PS (4 cm) on the side of PR opposite to Q.

5. With R as the centre, draw another arc with a radius equal to the length of RS (5 cm). The intersection point of the arc from P (step 4) and this arc from R is the vertex S. Join the points P to S and R to S with line segments.

6. PQRS is the required parallelogram.

Justification:

Triangle PQR is uniquely constructed by SSS criterion. Point S is uniquely located at the intersection of two arcs with radii PS and RS (where RS=PQ). Thus, the quadrilateral PQRS is constructed such that PQ=5cm, PS=4cm, PR=7cm, QR=4cm, and RS=5cm. Since opposite sides PQ=RS and PS=QR are equal, the quadrilateral PQRS is a parallelogram. The construction uniquely determines the parallelogram.

Case 3: When the lengths of two diagonals and the angle between them are given.

This construction relies on the property that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. If you know the lengths of the two diagonals and the angle at which they intersect, you can construct the two intersecting diagonal segments, which will determine the vertices of the parallelogram.

Let the diagonals be $d_1$ and $d_2$, and the angle between them be $\alpha$. We draw one diagonal, find its midpoint, and then draw the other diagonal passing through the midpoint at the given angle, ensuring its length is bisected.

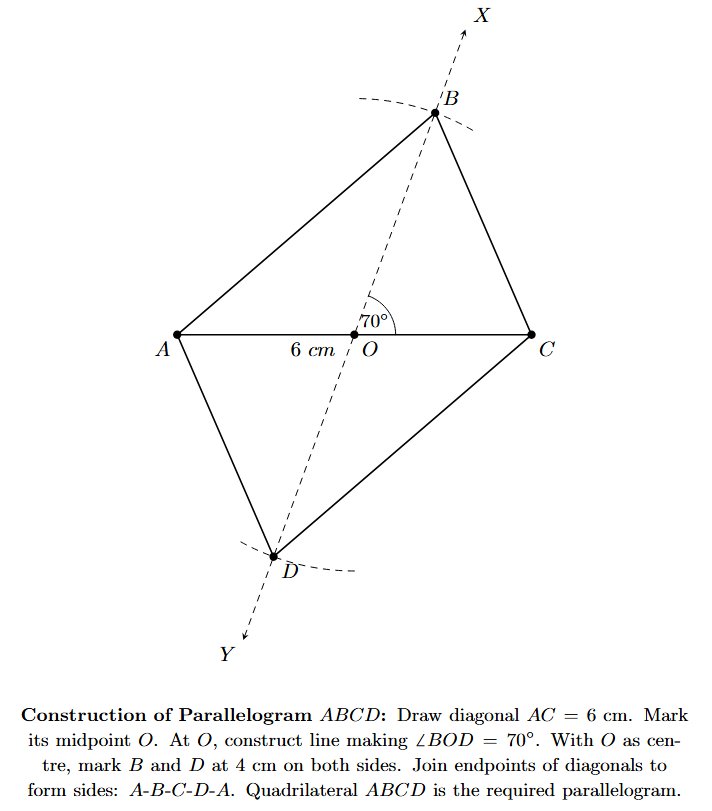

Example 3. Construct a parallelogram whose diagonals are 6 cm and 8 cm and the angle between them is $70^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of one diagonal = 6 cm | Length of other diagonal = 8 cm |

| Angle between the diagonals = $70^\circ$ |

To Construct:

A parallelogram with the given diagonal lengths and included angle.

Construction Steps:

1. Draw one of the diagonals. Let's draw a line segment AC of length 6 cm (representing one diagonal).

2. Find the midpoint of the diagonal AC. Since the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other, this midpoint will be the point of intersection of both diagonals. Mark the midpoint O of AC (AO = OC = $6/2 = 3$ cm).

3. At the midpoint O, construct an angle equal to the given angle between the diagonals ($70^\circ$). Draw a line XY passing through O such that it makes an angle of $70^\circ$ with AC (e.g., $\angle$COX = $70^\circ$).

4. The other diagonal is 8 cm long, and it is bisected by O. This means it extends 8/2 = 4 cm on either side of O along the line XY. With O as the centre, draw arcs of radius 4 cm intersecting the line XY on both sides of O. Mark the intersection points as B and D such that OB = OD = 4 cm.

5. Join the endpoints of the diagonals to form the sides of the parallelogram. Join A to B, B to C, C to D, and D to A with line segments.

6. ABCD is the required parallelogram.

Justification:

By construction, the segments AC and BD are line segments of lengths 6 cm and $4+4=8$ cm respectively. They intersect at point O, and O is the midpoint of both AC (AO=OC=3cm) and BD (BO=OD=4cm). A quadrilateral whose diagonals bisect each other is a parallelogram. The angle between the diagonals is constructed as $70^\circ$. Thus, ABCD is a parallelogram with the given diagonal lengths and the angle between them, and it is uniquely constructed.

Case 4: When one side and the lengths of both diagonals are given.

This construction method also relies on the property that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. If we know one side and both diagonals, we can construct a triangle formed by the known side and half the lengths of each diagonal. The point where the diagonals meet becomes a vertex of this triangle. From there, we can extend the half-diagonals to find the remaining vertices of the parallelogram.

Example 4. Construct a parallelogram PQRS where one side QR = 6 cm, diagonal PR = 8 cm, and diagonal QS = 10 cm.

Answer:

Given:

For parallelogram PQRS:

- One side: QR = 6 cm.

- Two diagonals: PR = 8 cm and QS = 10 cm.

To Construct:

A parallelogram PQRS with the given dimensions.

Analysis:

We know that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. Let the intersection point of diagonals PR and QS be O.

Therefore,

OQ = OS = $\frac{1}{2}$ QS = $\frac{1}{2} \times 10$ cm = 5 cm.

OR = OP = $\frac{1}{2}$ PR = $\frac{1}{2} \times 8$ cm = 4 cm.

We can start by constructing the triangle $\triangle$OQR, for which we know all three sides: OQ = 5 cm, OR = 4 cm, and QR = 6 cm.

Steps of Construction (Method 2):

Step 1: Draw the diagonal QS = 10 cm.

Step 2: Locate the midpoint O of the line segment QS using a ruler. Since QS = 10 cm, O will be at the 5 cm mark. Thus, OQ = OS = 5 cm.

Step 3: With O as the center and a radius of 4 cm (half of the other diagonal PR), draw arcs on both sides of the line segment QS.

Step 4: With Q as the center and a radius of 6 cm (length of side QR), draw an arc to intersect the arc from Step 3 on one side. Mark this intersection point as R.

Step 5: With S as the center and a radius of 6 cm (length of side PS, since PS=QR), draw an arc to intersect the arc from Step 3 on the other side. Mark this intersection point as P.

Step 6: Join PQ, QR, RS, and SP to complete the parallelogram.

PQRS is the required parallelogram.

Justification:

By construction, O is the midpoint of the diagonal QS. Also, the vertices P and R are located on a line passing through O such that OP = OR = 4 cm (by our arc construction). Thus, O is also the midpoint of PR. Since the diagonals QS and PR bisect each other, the quadrilateral PQRS is a parallelogram. By construction, the side QR = 6 cm, diagonal QS = 10 cm, and diagonal PR = OP + OR = 4 + 4 = 8 cm. All given conditions are satisfied.

Construction of Rectangles, Rhombi and Squares

Rectangle, Rhombus, and Square are special types of parallelograms, as discussed in the previous chapter. Due to their specific properties (like having all right angles or all sides equal, or diagonals being equal and perpendicular bisectors), their constructions require fewer measurements compared to a general quadrilateral or even a general parallelogram.

Construction of a Rectangle

A rectangle is a parallelogram with four right angles and equal diagonals. These properties allow us to construct a rectangle with only two given measurements. Let's explore the common cases.

Case 1: When two adjacent sides are given

Knowing the lengths of two adjacent sides is sufficient for construction, because all angles are fixed at $90^\circ$.

Example 1. Construct a rectangle PQRS with adjacent sides PQ = 5 cm and QR = 4 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of side PQ = 5 cm | Length of side QR = 4 cm |

To Construct:

A rectangle PQRS.

Construction Steps:

1. Draw a line segment PQ of length 5 cm.

2. At point Q, construct a perpendicular to PQ. This means constructing an angle of $90^\circ$ at Q. Draw a ray QX originating from Q.

3. Along the ray QX, mark a point R such that QR = 4 cm. With Q as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 4 cm intersecting ray QX at R.

4. Now, locate the fourth vertex S. We know that PS has length 4 cm (same as QR) and RS has length 5 cm (same as PQ). With P as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 4 cm.

5. With R as the centre, draw another arc with a radius of 5 cm. The intersection point of the arc from P (step 4) and this arc from R is the vertex S. Join the points P to S and R to S.

6. PQRS is the required rectangle.

Justification:

By construction, PQ = 5 cm, QR = 4 cm, and $\angle$Q = $90^\circ$. Also, RS = 5 cm and PS = 4 cm. Since opposite sides are equal, PQRS is a parallelogram. A parallelogram with one right angle is a rectangle. Thus, PQRS is the required rectangle.

Case 2: When one side and one diagonal are given

Since every angle in a rectangle is a right angle, a diagonal divides the rectangle into two right-angled triangles. We can construct one of these triangles using the given side and the diagonal (which acts as the hypotenuse).

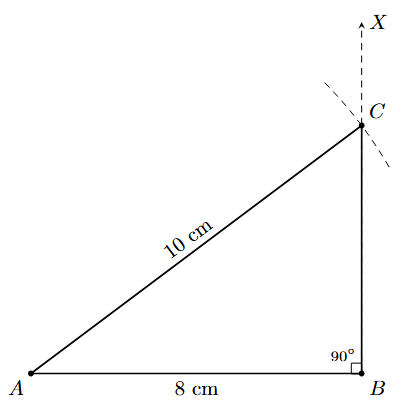

Example 2. Construct a rectangle ABCD with side AB = 8 cm and diagonal AC = 10 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of side AB = 8 cm | Length of diagonal AC = 10 cm |

To Construct:

A rectangle ABCD.

Steps of Construction:

Step 1: Draw a line segment AB of length 8 cm.

Step 2: At point B, construct a perpendicular line BX, as we know that the angle in a rectangle is $90^\circ$ ($\angle$B = $90^\circ$).

Step 3: With A as the centre and a radius of 10 cm (the length of the diagonal), draw an arc to intersect the ray BX. Mark the intersection point as C. Join AC. This forms the right-angled triangle ABC.

Step 4: Now, we will locate the fourth vertex, D. We know that in a rectangle, the opposite side CD is equal to AB. With C as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 8 cm.

Step 5: We also know that the diagonals of a rectangle are equal, so BD = AC = 10 cm. With B as the centre, draw another arc with a radius of 10 cm. The intersection of this arc and the arc from Step 4 is point D.

Step 6: Join AD and CD to complete the rectangle.

ABCD is the required rectangle.

Justification:

By construction, in $\triangle$ABC, $\angle$B = $90^\circ$. We have located point D such that CD = 8 cm = AB and BD = 10 cm = AC. In the quadrilateral ABCD, a pair of opposite sides are equal (AB = CD) and the diagonals are equal (AC = BD). A quadrilateral with these properties is a rectangle. Therefore, ABCD is the required rectangle.

Case 3: When one diagonal and the angle it makes with a side are given

This information allows us to construct the right-angled triangle formed by the diagonal and two adjacent sides.

Example 3. Construct a rectangle ABCD where diagonal AC = 6 cm and the angle it makes with side AB, $\angle$CAB = $30^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

- Length of diagonal AC = 6 cm

- Angle between diagonal AC and side AB, $\angle$CAB = $30^\circ$

To Construct:

A rectangle ABCD.

Analysis:

We use the property that the diagonals of a rectangle are equal and bisect each other. Let the diagonals AC and BD intersect at point O.

So, AC = BD = 6 cm.

Also, O is the midpoint of both diagonals. Therefore, OA = OC = OB = OD = $\frac{6}{2}$ = 3 cm.

Now, consider the triangle $\triangle$OAB. Since OA = OB = 3 cm, it is an isosceles triangle.

The base angles are equal, so $\angle$OBA = $\angle$OAB.

We are given $\angle$CAB = $30^\circ$, which is the same as $\angle$OAB. Thus, $\angle$OBA = $30^\circ$.

The angle at the center, $\angle$AOB = $180^\circ - (\angle\text{OAB} + \angle\text{OBA}) = 180^\circ - (30^\circ + 30^\circ) = 120^\circ$.

Since AC is a straight line, the adjacent angle $\angle$BOC = $180^\circ - \angle$AOB = $180^\circ - 120^\circ = 60^\circ$.

We will use this angle $\angle$BOC = 60° in our construction.

Steps of Construction:

Step 1: Draw the diagonal AC of length 6 cm.

Step 2: Find the midpoint of AC by measuring 3 cm from A (or C) and mark it as O.

Step 3: At the midpoint O, use a protractor to construct a ray OX such that it makes an angle of 60° with OC (i.e., $\angle$COX = $60^\circ$). Extend the ray OX backwards to form the line YOX.

Step 4: The other diagonal BD lies on the line YOX. Since the diagonals bisect each other, OB = OD = 3 cm. With O as the center and a radius of 3 cm, draw arcs to cut the ray OX at B and the ray OY at D.

Step 5: Join the points A, B, C, and D in order to form the quadrilateral.

ABCD is the required rectangle.

Justification:

By construction, the diagonals AC and BD are equal in length (AC = 6 cm, BD = BO + OD = 3+3 = 6 cm). They also bisect each other at point O. A quadrilateral whose diagonals are equal and bisect each other is a rectangle.

Furthermore, in $\triangle$BOC, we have OB = OC = 3 cm and $\angle$BOC = $60^\circ$, making it an equilateral triangle. So, BC = 3 cm. In right triangle ABC, sin($\angle$CAB) = $\frac{BC}{AC} = \frac{3}{6} = \frac{1}{2}$. This gives $\angle$CAB = $30^\circ$, which matches the given condition.

Case 4: When one diagonal and the angle between two diagonals are given

This construction relies on the property that the diagonals of a rectangle are equal and bisect each other. Knowing the length of the diagonals and the angle at which they intersect is sufficient.

Example 4. Construct a rectangle where the diagonals are each 8 cm long and intersect at an angle of $60^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of each diagonal = 8 cm | Angle between diagonals = $60^\circ$ |

To Construct:

A rectangle with the given properties.

Construction Steps:

1. Draw one diagonal, AC, of length 8 cm.

2. Using a ruler, measure the line segment AC, which is 8 cm. Locate its midpoint by marking a point O at the 4 cm mark. This point O is the midpoint, so AO = OC = 4 cm.

3. At O, construct a line XY that makes an angle of $60^\circ$ with the line segment AC.

4. The other diagonal, BD, is also 8 cm long and passes through O. This means it extends 4 cm on either side of O. With O as the centre, draw arcs of radius 4 cm to cut the line XY at points B and D.

5. Join the vertices A, B, C, and D in order to form the quadrilateral.

6. ABCD is the required rectangle.

Justification:

By construction, the diagonals AC and BD are equal in length (8 cm each) and they bisect each other at point O. A quadrilateral whose diagonals are equal and bisect each other is a rectangle. The angle between the diagonals is $60^\circ$ as required.

Construction of a Rhombus

A rhombus is a parallelogram with all four sides equal. Its specific properties (all sides equal, diagonals perpendicular bisectors of each other, diagonals bisect vertex angles) allow for construction with fewer measurements than a general parallelogram.

Common cases for construction include:

- Knowing the length of one side and the measure of one angle.

- Knowing the lengths of the two diagonals.

Case 1: Side Length and One Angle are Given

If you know the length of a side (since all sides are equal) and the measure of one angle, you can construct the rhombus. This is similar to the case of constructing a parallelogram with two adjacent sides and the included angle, but here the two adjacent sides are equal.

Example 5. Construct a rhombus JUMP with JU = 4 cm and $\angle$J = $60^\circ$.

Answer:

Given:

- Length of side JU = 4 cm (so JU = UM = MP = PJ = 4 cm)

- Measure of angle $\angle$J = $60^\circ$

To Construct:

A rhombus JUMP.

Steps of Construction:

Step 1: Draw a line segment JU of length 4 cm.

Step 2: At point J, construct an angle of $60^\circ$. Draw the ray JX originating from J.

Step 3: The vertex P is adjacent to J. Since all sides are equal, JP = 4 cm. With J as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 4 cm intersecting ray JX. Mark the intersection point as P.

Step 4: Now, locate the fourth vertex M. We know that UM = 4 cm and PM = 4 cm. With U as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 4 cm.

Step 5: With P as the centre, draw another arc with a radius of 4 cm. The intersection point of the arc from U (step 4) and this arc from P is the vertex M. Join the points U to M and P to M with line segments.

Step 6: JUMP is the required rhombus.

Justification:

By construction, JU = JP = PM = MU = 4 cm. A quadrilateral with all four sides equal is a rhombus. The angle at J is constructed as $60^\circ$. Thus, JUMP is a rhombus with the given side length and angle.

Case 2: Lengths of the Diagonals are Given

This construction uses the property that the diagonals of a rhombus are perpendicular bisectors of each other. Knowing the lengths of the two diagonals is sufficient.

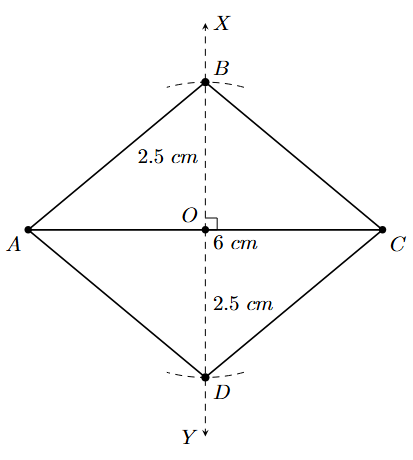

Example 6. Construct a rhombus whose diagonals are 5 cm and 6 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Length of one diagonal = 5 cm | Length of other diagonal = 6 cm |

To Construct:

A rhombus with the given diagonal lengths.

Construction Steps:

1. Draw one of the diagonals. Let's draw a line segment AC of length 6 cm (representing one diagonal).

2. Find the midpoint of the diagonal AC. Since the diagonals of a rhombus bisect each other, this midpoint is the point of intersection of both diagonals. Mark the midpoint O of AC (AO = OC = $6/2 = 3$ cm).

3. Construct the perpendicular bisector of AC passing through O. Draw a line XY that is perpendicular to AC at point O. (You can do this by constructing a $90^\circ$ angle at O or using compasses to draw arcs from A and C above and below AC and joining their intersections).

4. The other diagonal is 5 cm long, and it lies on the perpendicular bisector XY, with O as its midpoint. This means it extends $5/2 = 2.5$ cm on either side of O along the line XY. With O as the centre, draw arcs of radius 2.5 cm intersecting the line XY on both sides of O. Mark the intersection points as B and D such that OB = OD = 2.5 cm.

5. Join the endpoints of the diagonals to form the sides of the rhombus. Join A to B, B to C, C to D, and D to A with line segments.

6. ABCD is the required rhombus.

Justification:

By construction, the diagonals AC and BD intersect at O, which is the midpoint of both segments (AO=OC=3cm, BO=OD=2.5cm). This means the diagonals bisect each other. Also, the diagonals are perpendicular to each other at O ($\angle$AOB = $90^\circ$ by constructing the perpendicular). A quadrilateral whose diagonals bisect each other at right angles is a rhombus. The lengths of the diagonals are 6 cm and $2.5 + 2.5 = 5$ cm, as given. Thus, ABCD is a rhombus with the given diagonal lengths, and it is uniquely constructed.

Construction of a Square

A square is the most special type of quadrilateral. It is a regular polygon with 4 sides. It has all the properties of a parallelogram, a rectangle, and a rhombus. Because all sides are equal and all angles are $90^\circ$, we only need one measurement to construct a unique square: either the length of a side or the length of a diagonal.

Case 1: Side Length is Given

Knowing the length of one side of a square is sufficient because all sides are equal, and all angles are $90^\circ$.

Example 7. Construct a square with side length 4 cm.

Answer:

Given:

- Side length = 4 cm

To Construct:

A square ABCD with side 4 cm.

Construction Steps:

Step 1: Draw a line segment AB of length 4 cm.

Step 2: At point B, construct a perpendicular to AB. This makes an angle of $90^\circ$. Draw the ray BX originating from B.

Step 3: Since all sides of a square are equal, the adjacent side BC is also 4 cm. Along the ray BX, mark a point C such that BC = 4 cm. With B as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 4 cm intersecting ray BX at C.

Step 4: Now, locate the fourth vertex D. We know that AD = 4 cm and CD = 4 cm. With A as the centre, draw an arc with a radius of 4 cm.

Step 5: With C as the centre, draw another arc with a radius of 4 cm. The intersection point of the arc from A (step 4) and this arc from C is the vertex D. Join the points A to D and C to D with line segments.

Step 6: ABCD is the required square.

Justification:

By construction, AB = 4 cm, BC = 4 cm, $\angle$B = $90^\circ$, CD = 4 cm, and AD = 4 cm. Since all four sides are equal, ABCD is a rhombus. Since $\angle$B = $90^\circ$, it is a rhombus with one right angle. A rhombus with one right angle is a square. Thus, ABCD is a square with side length 4 cm.

Case 2: Length of a Diagonal is Given

Knowing the length of a diagonal of a square is sufficient for construction because the diagonals of a square are equal and bisect each other at right angles.

Example 8. Construct a square with diagonal length 6 cm.

Answer:

Given:

| Diagonal length = 6 cm |

To Construct:

A square with diagonal 6 cm.

Construction Steps:

1. Draw one of the diagonals. Draw a line segment AC of length 6 cm.

2. Find the midpoint of the diagonal AC. Mark the midpoint O of AC (AO = OC = $6/2 = 3$ cm).

3. Construct the perpendicular bisector of AC passing through O. Draw a line XY that is perpendicular to AC at point O. (You can construct a $90^\circ$ angle at O and extend the line, or use compasses to draw arcs from A and C and join their intersection points).

4. The other diagonal BD must also be 6 cm long (diagonals of a square are equal) and bisected at O. Along the line XY, mark points B and D on opposite sides of O such that OB = OD = $6/2 = 3$ cm.

5. Join the endpoints of the diagonals to form the sides of the square. Join A to B, B to C, C to D, and D to A with line segments.

6. ABCD is the required square.

Justification:

By construction, the diagonals AC and BD intersect at O, with AO=OC=3 cm, BO=OD=3 cm. So the diagonals bisect each other. Also, the diagonals have equal length (both 6 cm) and intersect at right angles ($\angle$AOB = $90^\circ$). A quadrilateral whose diagonals are equal and bisect each other at right angles is a square. Thus, ABCD is a square with the given diagonal length.